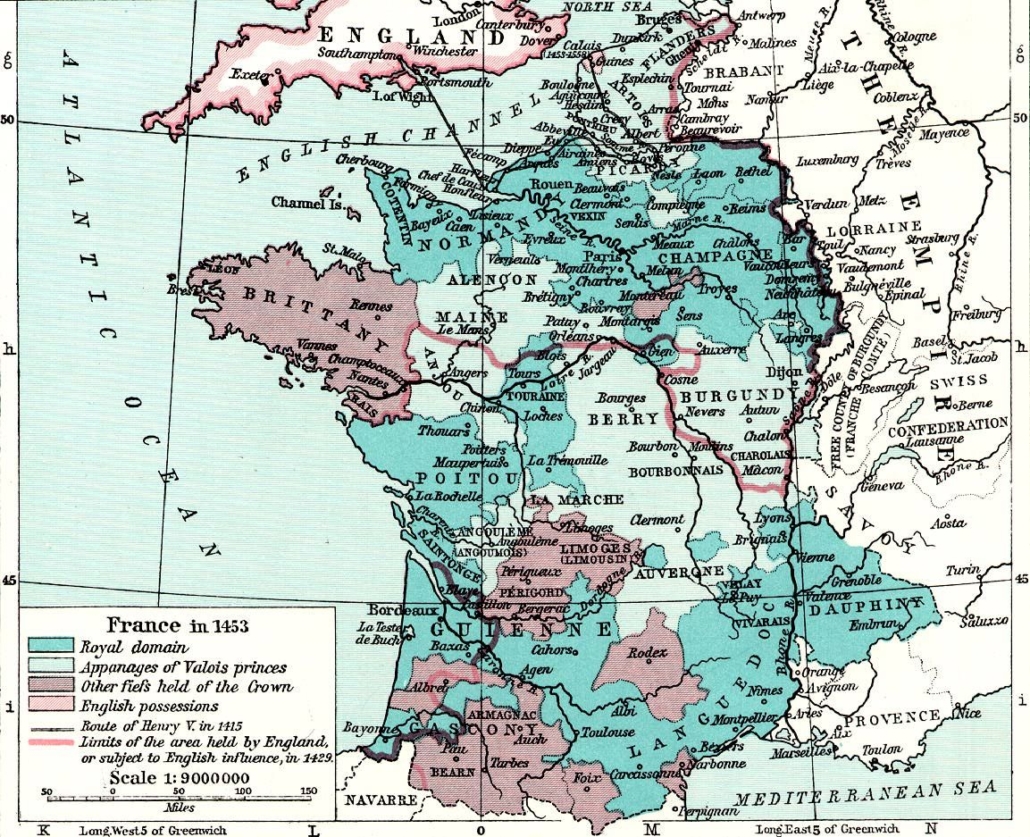

Late Medieval France

It is both surprising and infuriating that many conservatives, libertarians and those on the Right describe today’s political and financial order as “neo-feudalism.”(1) Surprisingly, because many of these commentators are trained academics(2) who should know better and infuriating, since feudalism and the glorious age which it reigned – the Middle Ages – if rightly understood and not denigrated could provide a paradigm for the reconstruction of the present social order after its inevitable collapse.

Many compare today’s political and economic configurations of vast wealth disparity and totalitarian democratic nation-states whose latest, and probably most egregious, abuse of power has been the lockdowns and compulsory face-mask edicts to combat a supposed deadly virus, with the conditions which existed under feudalism.

This is false.

Feudalism, and for most of the era which it existed, was characterized by political decentralization with little financial concentration of wealth.

Feudalism can be described as an arrangement between lords and monarchs with their underlings – vassals, dukes, earls, princes, counts, marquises, knights – in exchange for services. “Feudal tenure, whatever its minor adaptations,” writes medieval historian Carl Stephenson, “was essentially military because the original vassalage was a military relationship.”(3)

In return for military service, the vassal would receive a “fief” in the form of land, money, goods, or other benefits. “[A] fief,” Stephenson describes, “was the special remuneration paid to a vassal for the rendering of a special service.”

The relationship, unlike what modern commentators would have many believe, was not one-sided. While the vassal swore allegiance to his lord, the latter was obligated to provide his vassal with agreed upon “payment.” If the lord failed to fulfill his obligation, the vassal was free to break the agreement and find another lord.

The vassal, to receive his due from the lord, had to “faithfully give aid and counsel so that in every way the lord may be safeguarded as to person, rights, and belongings,” while the lord “has a reciprocal duty towards his faithful man. If either defaults in what he owes the other, he may justly be accused of perfidy.”(4)

The feudal relationship between lords and vassals had immense consequences – mostly positive – for medieval life. It helped shape the social order which impacted all aspects of society such as law, the political order (such as it was), war-making, and economics. The arrangement between lord and vassal was not really “political” as in the modern sense; it was more of a “contractual relationship” than that of power.

Lords and vassals and, for that matter, monarchs, did not create law or legislation but were subjected to the (natural) law. There was no monopolistic justice system, but a number of courts which were for the adjudication of disputes where cases could be appealed to different courts for redress. The myriad of public legislation regulating every aspect of modern man’s life, where most laws are not even read by legislators until they are enacted was, happily, not a feature of the Middle Ages. Law had to be “discovered” and based on custom and tradition in which all sectors of society had to abide by.

The feudal arrangement between lord, monarchs, and their vassals, where all had to live according to the law resulted, throughout the Western world, in a diffusion of power. Professor Stephenson illustrates how this effected France for centuries:

France, obviously, had ceased to be a state in any proper sense of the word. Rather, it had been split into a number of states whose rulers, no matter how they styled themselves enjoyed the substance of the regal power.(5)

The idea and reality of monarchial absolutism, which characterized the early modern era and which nation states would build upon for their own aggrandizement, was not part of the medieval period. In many areas, authority was held by dukes, princes and earls not based on political power, but one of trust, loyalty and contract.

The most vilified institution of the Middle Ages was serfdom. Yet, compared to the present epoch where the working classes are largely indebted, have had their individual liberties curtailed, and many are dependent on the welfare state for their financial survival, could serfdom be worse? Charles Coulombe contrasts

the serf, like laborers everywhere and at all times, had a hard life. He also could not be forced off the land, worked about 30 days a year for his lord (as opposed to the average American’s 167 for the IRS), and could NOT work on Sundays and the 30-odd Holy Days of obligation and certain other stated times. One may compare that to any current job description one wants to.(6) …

HOW WOULD OUR RIGHTS BE GUARANTEED UNDER A MONARCHY?

How are they guaranteed in any case? As Joe Sobran observed, “if voting actually changed anything, it would be illegal.”

The amount of taxation and its legitimacy in a society is ultimately determined by ideology. And, the ideology of the era frowned on taxation and those that were levied were done so grudgingly. It was the institutional framework of feudalism which limited taxation to the benefit of the social order.

Private property was considered sacrosanct and the violation of it an egregious offense. In the medieval world, taxation was a “sequestration of property” which the monarch only had the right to tax when it had “become traditional.” “The rights to property possessed by every individual member of the community,” according to historian Fritz Kern, “are an absolutely sacred part of the whole absolutely sacred legal order; the criterion of the rights in property of the individual as well as of the State is the good old law.”(7)

Kingship and Law in the Middle Ages: I The Divine Right of Kings and the Right of Resistance in the Early Middle Ages…

While many other passages could be cited, the existence of state power in feudal times is almost the polar opposite of the political situation which exists in the world today. It is inconceivable that the draconian measures taken by governments in response to the pandemic, which has ruined countless lives and allowed monetary authorities the world over to assume unseen power and control, could have never taken place during the Middle Ages. Nor could a system like communism with its oppressive top-down control happen. As noted, the medieval world was a world of de-centralized power.

Instead of naming the current age “neo-feudalism,” it is far better categorized as “neo-Progressive,” a term which describes the era of American history at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Progressive Era, despite the façade of supposed regulation of Big Business, was really the start of American corporatocracy – a cozy alliance between the State and Big Business to protect the latter, especially the financial sector, from competition. Each successive generation has seen this alliance become stronger leading to today’s situation of mega bailouts for the 1% at the expense of the middle class.

The learned detractors of feudalism who mischaracterize it are doing a great disservice to those who are seeking solutions to the myriad of social and economic crises which the Western world faces. The prime lesson that can be gleaned from feudalism is the diffusion of power. Attempts at reform of the current totalitarian democratic social order or the creation of alternative political parties to challenge the entrenched, corrupt, political order will result in failure.

Instead, all activities, movements, and more importantly, intellectual arguments should be directed toward the break-up of the nation state. Brexit, the recent victories of pro-independence parties in the Catalan elections, and the nascent secession movements in some states, such as Texas – TEXIT – should be encouraged and supported.

Happily, the pages of history provide a paradigm of a decentralized social order which thrived for nearly a millennium. Instead of bashing it, feudalism should be embraced and its principles incorporated into modern political discourse.

(1) The latest smearing of feudalism can be seen in Charles Hugh Smith, “The Coming Revolt of the Middle Class,” Zero Hedge, 28 January 2021.

(2) As an example, see Paul Craig Roberts, “Are We Brewing a New Feudalism?” Paul Craig Roberts Institute for Political Economy. 16 April 2020.

(3) Carl Stephenson, Mediaeval Institutions: Selected Essays, ed. Bryce D. Lyon (Ithaca, NY.: Cornell University Press, 1954, Cornell Paperbacks, 1967), 217.

(4) Carl Stephenson, Mediaeval Feudalism, 4th ed. (Ithaca, N.Y.: Great Seal Books, 1960), 20.

(5) Stephenson, Mediaeval Feudalism, 78.

(6) Charles Coulombe, “”Monarchist FAQ.” Tumblar House.

(7) Fritz Kern, Kingship and Law in the Middle Ages, trans. S.B. Chrimes (New York: Frederick A Praeger Publishers, 1956), 186.

https://www.