All installments in this series available here

In the last article, I discussed how in the 1930s, Hollywood was reluctant to make any anti-Nazi movies for a variety of reasons — chiefly that the Nazi government might invoke Article 15 of their film quota law to ban the studio that made it in Germany.

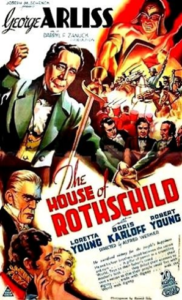

So if you can’t make anti-Nazi movies, what about a pro-Jew movie? If you can’t build some animosity against Hitler then maybe you can build some sympathy for Jews. Article 15 said you couldn’t make Germany look bad but it didn’t say anything about making Jews look good. That was the thinking of the two philo-Semitic gentiles behind the creation of the 1934 film The House of Rothschild. The House of Rothschild would end up being the greatest unintentional antisemitic propaganda movie of all time. They Live has nothing on The House of Rothschild. You can watch it here.

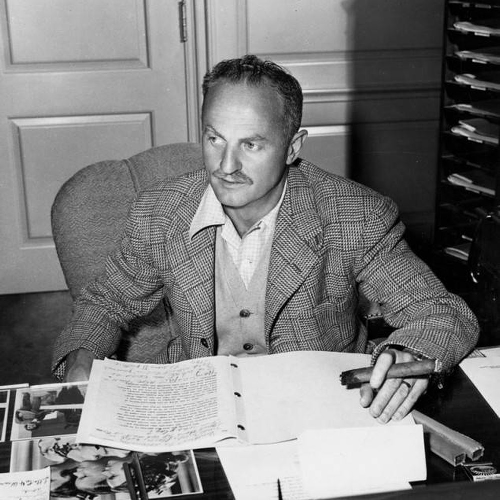

Darryl Zanuck was an ethnic Swiss Protestant raised in Nebraska and head of production at Warner Brothers. He had previously produced two pro-Jew movies that went on to be big hits: The Jazz Singer and Disraeli, which received an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture.

One day in 1933, Zanuck announced that he was giving everyone at Warner Brothers a pay raise. Studio boss Jack Warner was furious at this and countermanded Zanuck’s decision. This lead to a falling out between Zanuck and Warner Brothers. Zanuck soon left Warner Brothers to team up with Joseph Schenck of United Artists to start a new studio: Twentieth Century Pictures. Twentieth Century would later merge with Fox in 1935.

With his new company set up, Zanuck managed to persuade three big Warner Brothers stars to come join him in his new venture: Constance Bennett, Loretta Young, and George Arliss, whose performance in Disraeli had won him an Academy Award for Best Actor. Seeing that Zanuck and Arliss had such success with the pro-Jew film Disraeli, they thought it might be a good idea to make another. This was the origin of what would become The House of Rothschild.

British-born George Arliss was enthusiastic about the project as he was himself a great admirer of the Jews. “No one has a keener appreciation of what the world of science and art and literature owes to the Jews than I, and no one has greater sympathy with them in their unequal fight against savagery and ignorance.” Arliss traveled to England in order to research the history of the Rothschild family but not before creating a minor controversy by taking a German ship to get there.

I had never watched The House of Rothschild before I started researching this article. I was aware of its existence but I had no interest in watching a movie about Jews, nevermind one that portrayed the Jews as the heroes nevermind one that portrayed the freakin’ Rothschilds as heroes. But then I stumbled upon the factoid that Joseph Goebbels allowed The House of Rothschild to be shown in Nazi Germany with only minor edits, and that got me curious. I decided to watch The House of Rothschild to see if I could figure out what the Nazis liked so much about it and. . . they should have called it The JQ: The Movie. It has all the tropes and quite a few canards as well. Only bluepilled gentiles could have made this movie.

The House of Rothschild opens in 1780 in Frankfurt, Germany. In the opening shot, we see a sign that says “All Jews must be in the Jew Street by sundown. — Chancellor of Prussia.”

In his house on Jew Street, we see family patriarch Mayer Rothschild, his wife, and their five sons. Mayer is counting his stacks of money and business is doing gangbusters. Mayer’s son comes in to tell him that the taxman is coming. So then all the Rothschilds start scrambling to hide all their giant stacks of money. They cover up the expensive pot roast they are cooking and Mayer tells his kids to “look hungry.” When the taxman arrives, Mayer shows him fake account books to make him think that business is going badly. The taxman is not fooled, but for a bribe of 5,000 gulden, he reduced Rothschild’s taxes from 20,000 to 2,000 gulden.

Now, what you’re supposed to think watching this is “Well, why should the Jews pay their taxes to a government that is so mean to them? They segregate them and make them live in that tiny ghetto. I would dodge my taxes, too.” But watching that scene redpilled, you’re just like “Man, these Jews are really greedy. They lie and resort to all kind of deception to avoid contributing to the common good of the nation and when the lies don’t work, will make illegal bribes to avoid paying their fair share. The guy’s a money lender. It’s not like he had to do any strenuous labor to get that money. The guys working the coal mines are paying their taxes. What the hell is this guy’s problem?”

We then see Mayer Rothschild on his deathbed. He orders his sons to split up and start banks in a different major European city. “Work and strive for money! Money is power! Money is the only weapon that a Jew has to defend himself with!”

Honestly, I don’t know what I am supposed to think of this. That society is forcing him to become fabulously wealthy? That he would love nothing more than to be out there digging ditches but it’s a matter of life and death that he loan money with interest? That he engages in usury because people hate Jews and not the other way around?

Mayer Rothschild dies and his sons split up. One Rothschild stays in Frankfurt, one goes to Paris, one to Madrid, one to Naples, and Nathan Rothschild, their leader and the protagonist of The House of Rothschild, goes to London. The Napoleonic Wars break out, and every European country turns to the Rothschilds for funding. The Rothschilds side with the allies over the French. Because the Allies won the battle for Rothschild funding, they are at last able to defeat Napoleon and he is sent Elba.

Now, what you’re supposed to think watching that is “Well, it’s a good thing we have these Jews around to save us from that tyrant Napoleon. Lord knows what that Corsican monster would have done were it not for these Jews.” But watching this movie redpilled, you think “This small clique of Jews is deciding the fate of Europe.”

With Napoleon in Elba, Nathan Rothschild gets word that France is going to receive the largest loan of all time to help them rebuild. All the banks of Europe submit their bids. The Rothschild bank submits the best bid, but to Nathan’s shock, it is announced that the loan has been granted to Barings of London. Nathan demands an explanation, and the antisemitic Count Ledrantz (played by Boris Karloff of Frankenstein fame) tells him that it is because Nathan is a Jew. Nathan then uses his vast wealth to manipulate the stock market in such a way that Barings bonds become unsellable and they are forced to transfer the loan to the Rothschilds at a significant financial loss to themselves.

Now, what you’re supposed to think watching that is “Well, serves them right for being antisemites!” But watching that scene while redpilled, you think “Jews manipulate the stock market for their personal gain and to resolve petty grudges at the expense of gentiles.”

Zanuck’s business partner Joseph Schenck actually did raise some concern about including Boris Karloff’s antisemitic character, because he would afraid that audiences would start cheering for him after his lines.

After that episode, Nathan Rothschild becomes stridently racist against gentiles and forces his daughter (played by Lorretta Young) to break off her engagement to Captain Fitzroy. In retaliation for outmaneuvering him, Count Ledrantz starts an antisemitic propaganda campaign that causes anti-Jewish riots to break out all over Europe.

Napoleon escapes from Elba and regains power. Four of the Rothschild brothers want to side with Napoleon this time, as he is more pro-Jew and it would be the smarter option financially, but Nathan says no. Napoleon is such a tyrant that the Rothschilds must put the good of humanity above their own self-interests. They set up a meeting with the Allies, and Nathan bluffs them that he will back Napoleon unless they call off the riots and grant Jews equal rights. The allies have no choice but to agree.

With Napoleon back and on the move, the London stock market goes into a panic. Nathan dumps his entire fortune into it to keep it from crashing because he is just such a humanitarian. When news of Waterloo comes in, the market recovers, and Nathan, because he bought the dip, becomes the wealthiest man in the world.

Now, what you’re supposed to think watching that is “Thank God for those Rothschilds or else we would all be speaking French right now.” But watching the film redpilled, you think “These Jews become fabulously wealthy off war and human suffering without ever having to pick up a gun themselves. European leaders are forced to grovel at their feet and give in to their every demand or else the Jews will allow them to be destroyed by their enemies.”

The House of Rothschild is a movie that could only have been made by bluepilled philo-Semitic gentiles. A Jew would have known to avoid the tropes and an anti-Semite would have emphasized them in a much more heavy-handed way. The House of Rothschild seems to skip along casually dropping antisemitic tropes blissfully unaware that it is doing so.

When the Anti-Defamation League learned of the plot of The House of Rothschild, they started freaking out. They immediately recognized the tropes. The ADL sent a letter to Zanuck to try to get him to cancel the film:

The impression which will be made is that the concentration of wealth in the hands of one international Jewish family invested that family with indisputable power to determine the destinies of nations. The very fact that Christian nations must beg of the Jewish Rothschild family for money with which to protect their own existence will in itself create a most undesirable reaction.

ADL national secretary Leon Lewis called it “one of the most dangerous presentations” of Jews of the era. He urged Zanuck to get in touch with “those among our people . . . who have been devoting all their energies in the past few months to stemming the rising tide of hatred against the Jews.”

Zanuck responded to the ADL:

I am not a Jew and I have never heard of this “rising hatred of Jews” that you speak about in your letter, and I am inclined to believe that it is, more or less, imaginary as far as the general public is concerned. We make pictures for the broad general public rather than the minority and I will guarantee you that if there is such a thing as a “rising hatred for the Jew in America” our film version of ROTHSCHILD will do more to stop it than anything, from the standpoint of entertainment.

Having no luck with Zanuck, the ADL then turned to the Hays office. In a letter to Will Hays, the ADL stated:

It is important that nothing be done now that might possibly feed the unreasoning prejudice against the Jews which is in some places. A widespread factor in this unfair and prejudiced attack is the false allegation that all Jews acquire money for power, with the inference that such power may be misused. The historical prominence of the house of Rothschild is such that hostile propagandists have tried to make the very name a synonym for sinister, world-wide political power, growing out of accumulated riches. The fact that in the case of the Rothschilds the power of money was rightly used may be overshadowed by the greater impression of the Rothschilds as an example of Jewish power through domination by money.

The Hays office agreed that the film had the potential to cause problems. In response, Zanuck put on some preview performances of The House of Rothschild and sent Hays 175 preview cards from audience members praising the film. The National Council of Jewish Women even previewed the film, giving it their thumbs up. The Hays office was satisfied that people were not picking up any antisemitic vibes from the movie and dropped the matter.

Having failed with Zanuck and the Hays office, the ADL had another option. They appealed to the Jewish studio heads throughout Hollywood to see if they could use their influence to kill the movie. The ADL sent a telegram to Louis B. Mayer, the most powerful man in Hollywood and a majority shareholder in Twentieth Century Pictures:

OUR SITUATION AT THIS TIME MORE CRITICAL THAN ANY TIME HERETOFORE DEMANDING OF EACH THE GREATEST CAUTION STOP IN NORMAL TIMES NO HARM MIGHT BE ANTICIPATED ACUTE CONDITIONS NOW MUST BE CONSIDERED STOP WILL YOU COOPERATE TO PREVENT PICTURE AT LEAST DURING CRITICAL PERIOD.

Louis B. Mayer sat down and watched The House of Rothschild with Harry Cohn, head of Columbia Picture. Neither of them found anything wrong with it. The ADL then went to Louis B. Mayer’s rabbi Edward Magnin to see if he could talk sense into Mayer. According to Leon Lewis, Magnin “lit into” Mayer and told him that

the conditions in the industry were responsible for a great deal of the prejudice existing and that it is ironical that on top of it they should show so little sense as to promote a film of this type at this time. He said they were digging their own graves and that they would alienate the Jews as well.

The ADL also appealed to Jack Warner of Warner Brothers to see if he could do something to stop the movie. The problem with Jack Warner is that Zanuck was his former employee and it would have been a bad look. Zanuck quits Warner Brothers after a falling out, starts a new company, and then Jack Warner immediately tries to kill his new film. Jack Warner would have ended up looking ultra-petty. Plus, Zanuck was a gentile and Warner was a Jew, so that might in itself create an antisemitic impression.

In the end, the ADL was unable to stop the release of The House of Rothschild. It would end up being a big hit for Twentieth Century Pictures and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture where it would lose to It Happened One Night.

As for The House of Rothschild, the Nazis loved it. They would later use footage from The House of Rothschild in their antisemitic magnum opus Der ewige Jude. Twenty minutes into Der ewige Jude, they play a clip from early in the movie and the narrator states “Here we show a scene from a film about the Rothschild family. It was made by American Jews, obviously as a tribute to one of the greatest names in Jewish history. They honor their hero in a typically Jewish manner, delighting in the way old Mayer Amschel Rothschild cheats his host state by feigning poverty to avoid paying taxes.”

After The House of Rothschild, it became the consensus around Hollywood that it might be a good idea not to make any more movies about Jews just to be on the safe side.

In 1937, Warner Brothers would release The Life of Emile Zola, a film about the eponymous French writer and his experiences during the Dreyfus Affair (watch it here). The Dreyfus Affair was a controversy that rocked French society for several years and involved a Jewish military officer who was accused of spying for Germany. Dreyfus’ Jewishness was a pretty central part of the controversy. Anti-Dreyfusards claimed Dreyfus sold out his country to Germany because Jews are rootless cosmopolitans incapable of real patriotism or loyalty. Dreyfusards claimed he was being scapegoated because he was a Jew. But in The Life of Emile Zola, the word “Jew” is not spoken a single time.

It would take several years longer for Hollywood to address the issue of Jews than Nazis. Confessions of a Nazi Spy, Hollywood’s first-ever anti-Nazi movie, mentions that the Nazis are racist but never addresses the persecution of minorities at all.

The first Hollywood movie to address the persecution of minorites in Germany was the 1940 Jimmy Stewart film The Mortal Storm (which you can watch here). But even in The Mortal Storm, the persecuted minority group is never identified as “Jews.” They are only ever referred to as “non-Aryans.”

The original screenplay for The Mortal Storm was apparently much more explicit about who was being persecuted and even included a scene where a Jewish father gives a speech to his mischling son on Jewish pride. “I’m proud to be a Jew. I’m proud to belong to the race that gave Europe its religion and its moral law — much of its science, too — much of its genius, in art, literature, and music. Mendelssohn was a Jew, and Rubenstein — the great English statesman, Disraeli, was a Jew, and so was our poet Heine, who wrote the ‘Lorelei.’”

This scene was cut out at the last minute — halfway through production, in fact. The reasons are obscure, but all signs point to the decision being made by the MGM big man himself, Louis B. Mayer.

Louis B. Mayer’s rabbi Edward Magnin offered a likely explanation. Magnin was granted a preview of The Mortal Storm, approved of the movie, and was not opposed to MGM’s decision to forego naming the Jew:

One thing in favor of our side now is that people may be sympathetic, (but not much), when they fear and now they are afraid. They hate the thing they fear — that is the answer. They can still hate Jews and still fear Germany!

In other words, it was less important that people like Jews than that they hate Nazis.

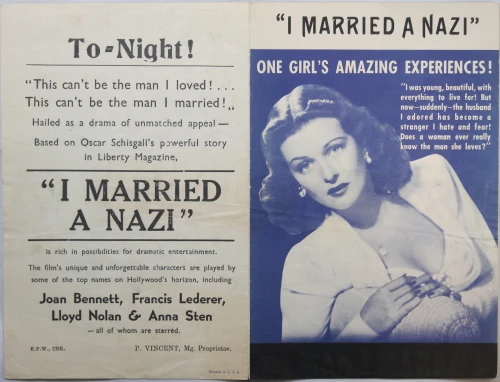

The first Hollywood movie to explicitly reference Jews in relation to Nazis was the Fox movie The Man I Married AKA I Married a Nazi (watch it here). This is a funny little movie and completely absurd. In The Man I Married, Joan Bennett plays an American art critic who is married to a good-natured German immigrant played by Czech-born Jewish actor Francis Lederer (who had previously played the Nazi spy in Confessions of a Nazi Spy).

Joan Bennett, Lederer, and their 7-year-old son travel to Nazi Germany. Once there, Lederer reunites with a childhood friend played by Anna Sten. She starts taking Lederer to Nazi rallies, and he immediately becomes a diehard Nazi. Suddenly, Joan Bennett now finds herself married to a raving Nazi fanatic.

The idea that Hitler and Nazi ideas had a magical power to turn ordinary people into hysterical bloodthirsty maniacs was be promoted even back then, before the United States had even entered the war.

The movie has a twist ending that I am going to spoil for you. At the end, Bennett is disgusted and wants to return to America, but Lederer insists on staying in Germany and keeping their son. Lederer gets into an argument with his anti-Nazi father about it and then his father drops a bomb on him: Lederer’s mother was actually Jewish which makes Lederer himself a half-Jew. Furthermore, dad threatens Lederer that if he does not let Bennett return to America with their son that he will report him to Nazi authorities. Bennett gets the kid and goes home.

That is the first time Hollywood explicitly references the Nazi persecution of Jews by name. The Man I Married was released in August of 1940.