("Both the “nationalist” Jewish Bund and the Jewish Bolsheviks in Hungary (or Russia), aimed to destroy the dominance of the host nation’s traditional ethnic group over their own country, leading to easier access for them to more power within its institutions" -

And that is exactly how DaSynagogue of Satan operates everywhere! - CL)

by

7600 words

After the Jewish activism and strategies to gain power that we have seen so far, it is worth critically analyzing in more detail the persistent and unremitting misrepresentations, distortions and, shall we say, manipulations of a certain aspect of mainstream historiography. The mainstream narrative is that the blatant Jewish presence among the Bolsheviks does not matter, on the one hand, because they “were not Jews,” and on the other hand, if it is strange that Jews were so prominent in the upper echelons of Communist power, it is only because of discrimination by Hungarians (or Russians, etc.), and it is not the Jews who are to blame for all this—so goes the obvious conclusion of this logic. How much does ethnic identity play a role, and how much does ethnic character matter? Or both at the same time? In the following, these and related elements, are presented and, if necessary, refuted.

Jews and philosemites who deny the Jewishness of the Bolsheviks almost always make sure to quote a half-sentence of Béla Kun, who said at a meeting in 1919: “My father was a Jew, but I did not remain a Jew, because I became a Socialist, I became a Communist.” We will touch on the concept of identity-by-proxy later, but for now, let us look at this quote in its context. Below is the full, relevant part of his speech from the National Assembly of the Councils, delivered on June 21, 1919:

Here in this room, my comrades — I say it openly — there are those who are waiting for the dictatorship of the proletariat to fall, to betray it. (Great noise and shouts: “Shame!”) Here sits a slave judge. How, then, is the Red Army to fight, how is the Red Army to be in the mood, when here at the Council Congress and the Party Congress anti-Semitic agitation, pogrom agitation is taking place? (That’s right! That’s right!) I, comrades, will not be ashamed that, as a Jew, I’ll deal with this issue. My father was a Jew, but I did not remain a Jew, because I became a Socialist, I became a Communist, (True! True!), but it seems that many people who were born in other religions, in Christian religions, remained Christian Socialists. (Minutes, 1919, 204–205)

Kun not only does not deny his Jewishness, but literally refers to himself as a Jew, and then it becomes clear that he is talking about the Jewish religion (contrasting it to those born in “other religions”), which he left behind as a paternal legacy, and chose secular Bolshevism instead, as so many Jews who rejected religion did in the past—while still identifing as Jews and being seen by others as Jews. Moreover, Kun is not abandoning his Jewishness here, but on the contrary: he is fretting, from a Jewish point of view, about the fact that anti-Semitism lurks even in their circles because of the common perception of the overwhelming prominence of Jews, and promises to put an end to it. Moreover, he tells the audience that it is the comrades born into the Christian religion (i.e., not Jewish, Hungarians) who are suspect, as if they were not capable of fully embracing Bolshevism, and thus attacks the typically Hungarian Christian Socialists who are attracted to Socialism. What emerges from all this is rather the image of a Jewish Bolshevik, since it is not anti-Christianity, or anti-Hungarianism, that he is targeting (there were plenty of those at the time), but the mere assumption of anti-Jewishness, which he considers all the more important as a Jew, and which encourages him to take a committed stand (with the approval of others), and is, moreover, suspicious and hostile towards Hungarians and Christians, but not religious Jews. It is revealing that we keep hearing only that one snippet of all this, without critical analysis.

Béla Kun (front) with Tibor Szamuely (back, left)

Béla Kun (front) with Tibor Szamuely (back, left)

In any case, Kun’s suspicions were reflected in the statement of Béla Vágó (Weisz), a Commissar, who expressed similar views that day:

When that rural farmer, that priest, or that count, makes anti-Semitic jokes, incites a pogrom, and agitates out there in the Hinterland, then, my dear comrades, the decidedly anti-Semitic spirit which was expressed here at the Congress by some of the delegates contributes very excellently to this agitation. Dear comrades! If an old organized worker has the courage or the folly to say that there are people running around in the country who have not even had their sidelocks properly cut off, then, my comrades, we should not be surprised if they agitate throughout the country that Jews are in power, that Jews want to destroy the whole country and that Jewish rule is destroying this poor Christian Hungary. When such a statement is made, when this spirit prevails among some of the comrades, do not be surprised if this spirit, this agitation and this poison are felt throughout the country in this way.

I have just been in a few places, my comrades, where the wildest counter-revolutionary agitation was going on among the peasants. And do the comrades want to know what the material of this agitation was? The material of the agitation was that while the poor man is starving and miserable, the Commissars are always driving around in their cars here in Budapest, while the working class cannot live, the People’s Commissars are living in splendor and prosperity, and those rascally Jewish kids with sideburns who are sent out into the countryside, who are traveling the country, want to take away the wealth and happiness of the poor man. (Ibid., 210)

Later, Vágó-Weisz shared a thought-provoking speech with the audience. It reveals that, borne out of his frustration about anti-Semitism, he had come up with a strategy. The solution to anti-Jewish sentiment was to force the peasants to serve the Soviet Republic:

The land of the peasant should not be taken away, but his hands and feet should be tied in fetters, and he should be forced to serve the Soviet Republic by the force of dictatorship. (Ibid., 211)

And not in just any way, but by making him see the rich peasant as his enemy, and not the Jew—while it is the Jewish regimes who oppress him with dictatorship. Note the train of thought:

Today the rebellion, today the discontent, is against the Jews. The Jew is the cause of everything, the Jew has taken everything from the poor man, the Jew is the cause of the terrible conditions of subsistence of the landless peasantry working in the countryside. On the contrary, I recommend that there should be no room for much criticism, but that one should go straight out into the village and make the poor peasantry aware that their interests are contrary to those of the rich peasantry, because the whole pogrom agitation, the whole counter-revolutionary fire was started by the landowning peasantry.

A voice: And the clergy! (Ibid.)

Vágó-Weisz then adds: “we must go out into the villages and make the peasantry aware that the class struggle between the rich and the poor must break out there too. The rich peasantry is full of food, its larder is overflowing with fat, ham, wine, bacon (True! True!) and the situation of the poor peasantry can be solved no more by the beating and plundering of the Jews than that of the industrial worker” (ibid.). The Commissar, who personifies the Jewish question in an almost caricature-like manner, would thus solve this anti-Jewish “peasant question” by “placing it only on the basis of the class struggle to be waged in the village” (ibid., 212). He notes that the anti-Jewish sentiment is “outrageous and worrisome” and that the Jew-critical voices at the meeting could be made known to the country, thus “contributing greatly to the incitement against the Jews, instead of the capitalists, instead of the rich peasants, against the dictatorship” (ibid.).

On the same day, the apparently non-Jewish György Nyisztor, Commissar for Agriculture, in his speech, said: “I am convinced that if anti-Semitism gets a foothold here, the proletarian dictatorship is dead” (ibid., 216). He also explains that anti-Christianity from their circles generates very considerable anti-Semitism and counter-revolutionary fervor and that it must be communicated “strictly outwards” that such things will not be tolerated by the authorities, with an emphasis on equality:

It’s not enough to say that there should be no anti-Semitism here, but every snot-nosed kid — and I say the same thing — who is not careful and reckless, must be punched in the mouth. (Loud agreement.) Because then, to say that anti-Semitism is spreading, and one snot-nosed kid insults the religious beliefs of thousands and thousands of people (True! True!) we must fight against this if we want there to be no anti-Semitism (True! That’s right!) not only must they be punished, but it must be written in bold letters that in this country there are no Jews or Hungarians, no one in the proletarian dictatorship because there are no Jews, Christians or Reformed, but only Socialists and Communists. (Agreement!) This, my comrades, must be done, strictly outwardly, not only to punish someone but also to write it in big, bold letters so that they can read that we can act against this. Indeed, in the countryside, even today, it is the evils of carelessness, and the insults against religion, that are the cause of the counter-revolutionaries and counter-revolutionary movements in so many places. (Ibid.)

Note the choice of words: the problem with the anti-Christian person is that he is “not careful and reckless,” and that they have to communicate this principle of equality “strictly outwardly”—the aim of which is “to avoid anti-Semitism.” Anti-Christianity is a mere logistical issue, while anti-Semitism is a real problem, the elimination of which is a concrete goal. After all this, another non-Jew, János Horvát, spoke out in response to the complaints of anti-Jewishness indirectly addressed to him above. Ironically, he says of himself that “anyone who has been in prison for sedition and incitement against the Church, who has trashed the Church itself, cannot be an anti-Semite” (ibid., 218), again showing that the above concern about anti-Christianity was entirely a matter of communication strategy.

In the documents, we find numerous instances of concern about anti-Semitism and proposals for solutions to eradicate it, contradicting the mainstream narrative that these Judeo-Bolsheviks were unconcerned with anti-Semitism (and suggesting that they were unconcerned with their own Jewishness). For example, still on June 21, a member reported that a telegram message was intercepted, in which someone was trying to influence a person delivering food, to stop giving it to Jews. As we learn “When the gentleman arrived, the revolutionary tribunal arrested him” for this (ibid., 222). At their meeting two days later, we learn that the “immediate investigation” into the matter concluded that the message sent had called for the exclusion of “provincials,” not Jews, and that someone somewhere may have transcribed it “probably with a counter-revolutionary purpose” (ibid., 257). This shows that even during the time when they had to deal with serious problems, their paranoia about anti-Semitism persisted.

Manifestations of Not Belonging: the Case of József Pogány-Schwartz

One of Hungary’s most prominent rationalizers of the Jewish involvement in the bloody regime of terror in the last few years has probably been the historian Péter Csunderlik (whose ethnic background is unclear). His few supposedly convincing arguments have been published in almost the same form in several places over several years, albeit as a result of separate grants. According to him:

Despite the fact that the members of the Revolutionary Governing Council of Jewish origin who led the proletarian dictatorship for only 133 days (in an atheist and internationalist political movement) had no “Jewish” identity, the (far-right) discourse tradition that consolidated after 1919 was that the proletarian dictatorship was nothing but a “Jewish dictatorship.” However, the high proportion of Jews in the labor movement is not explained by the conspiracy theory of “Judeo-Bolshevism,” but by the fact that, despite the legal emancipation achieved – the Israelite religion became a recognized denomination in 1895 – Jews continued to suffer discrimination in everyday life. For them, joining the internationalist movement gave them the opportunity to leave behind the disadvantage of being “Jewish,” which, in the eyes of many, was an obstacle to their full integration into society. (Csunderlik, 2020)

Csunderlik makes two mistakes here: one is that he still tries to give the impression that Jewry is only a religious community, thus emphasizing atheism in an attempt to obscure the Jewish character of the Bolshevik system, whereas by now presumably everyone understands that Jews are an ethnicity, first and foremost, and only after that possibly a religion (for genetic research, see among many: Hammer et al., 2000; Ostrer, 2001; Nebel et al., 2001; Need et al., 2009; Hammer et al., 2009; Atzmon et al., 2010; Ostrer & Skorecki, 2013; Carmi et al., 2014, etc.). This particular obfuscation was already obvious a hundred years ago. That an “atheist and internationalist” Jew should not have a Jewish identity is fundamentally ridiculous (see MacDonald 2002/1998, Ch. 3), and presumably many atheist Jews would take offense to such a claim. (In line with both adjectives: on the clear Jewish identity of Sigmund Freud and Sándor Ferenczi, see my earlier analysis in Csonthegyi, 2024, just to give an example, but we will also look at the question of identity in more detail later.)

The other mistake he makes is one he is not even noticing perhaps; refuting himself with the same breath. If these Jews were hoping to end their discomfort with “discrimination” by their dictatorship, it takes on the character of a kind of ethnic revenge or at least a Jewish-rooted motivation. If the aim of their dictatorship—or at least its significant motivation—is to “leave the disadvantage of being ’Jewish’,” then surely the aim is to free their Jewishness from constraints: to transform the host country and nation, so that it is not anti-Semitic. This is a distinctly Jewish motivation. The argument is that these Jews somehow wanted to leave their Jewishness behind in all this, but why, in this case, they did not attempt to become Hungarian, rather than transform Hungarians into a nation tolerant of their Jewishness, is the narrative of a confused logic. The explanation is presumably that the Hungarians would not have accepted the Jews as Hungarians either way, so there was no alternative, but to force Hungarians to change, at any cost—even that of a militant dictatorship (which, coincidentally, was ruled by Jews). Whichever way we look at this explanation, the Jewish motivation is clear.

Csunderlik, however, sees this explanation as sufficient: the frustration and alienation caused by the intolerance of Hungarians, is the explanation for the staggering Jewish predominance—as for the rest of his article, he fills it with his horror at the opinions of “anti-Semites,” and we can not but scratch our heads, and wonder; what does it say about these Jews, that discrimination and other potential inconveniences, are driving them to unleash a subversive, mass-murdering dictatorship? “Be nicer to them, or they will slaughter you” is, to the sober observer, a not very confidence-inspiring basis for coexistence. We should be lucky that gypsies, people with sexual aberrations, or perhaps the deaf, and the disabled (because of experiences with similar discrimination) are not building terror squads and taking over our country.

It is also worth mentioning in a few words, that to mention this discrimination in the context of the extremely influential Jewish population, which had an extremely high presence in the elite strata, is perhaps a particularly bold undertaking. Csunderlik’s evidence to this is a 1912 Népszava article entitled “No Housing for Jews.” That this kind of thing was the cause of the Soviet Republic is, according to this historian, a sound theory, but to consider the authoritarianism of the Jews as “Jewish” is, according to the same historian, either unbelievable, or a “conspiracy theory”… Indeed, in his earlier book on the Galileo Circle, Csunderlik (2017, 28) put it this way: “by the early 1900s, the leaders of the Hungarian labour movement were already over-represented among those of Jewish origin, for whom joining the internationalist movement provided an opportunity to leave behind the disadvantage of their ’Jewishness,’ which, in the eyes of many, was an obstacle to their full integration into society.” His reference here is to “the case of György Lukács, who went from bourgeois intellectual to Marxist ideologue.” This is, again, a self-contradiction, since what kind of desire for “integration” made the “bourgeois” Lukács, who lived much better than many Hungarians, decide to participate in a bloody dictatorship that massacred Hungarians? How can we make sense of this? Are not only the Jews discriminated against in the housing advertisements. Are even the well-off intellectuals becoming bloodthirsty, out of some kind of desire to fit in? It is also hard to reconcile this theory with the reality that many of the Jews involved in the events in Hungary have tried to start revolutions internationally. Thus, for example, in March 1921, József Pogány-Schwartz and Béla Kun-Kohn himself were sent from Moscow to Germany—not motivated by a desire to assimilate, but to help the Jewish communists there (Klara Zetkin, Paul Levi, Rosa Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches, etc.) to spark off a revolution. Pogány also worked with the Communist Party USA under the name of John Pepper with his fellow Jewish Communist Party members Maksymilian Horwitz (Valetski) and Boris Reinstein (Draper, 1957, 364).

It is this kind of mental contortionism that results when we refuse to accept the diversity of ethnic characters, and the reality of the group conflicts that have been a feature of human history and in particular the history of the Jews, of which the Judeo-Bolshevik–anti-Bolshevik confrontation is but one example.

However, according to Csunderlik’s article, “the post-1919 policy of legitimizing the redistribution of social wealth through anti-Semitic ideology” invoked Judeo-Bolshevism as a pretext, and “not because of the involvement of Jews in 1918–1919.” He draws this conclusion from the fact that disabled soldiers who sympathized with the Communists were not punished under Miklós Horthy, but it is not clear what the party sympathies of non-Jews have to do with the Jewish question—it’s obvious that the Jews had the power in the Kun regime. It also remains obscure why the author pretends that it is not logical that a dictatorship by Jews is called a Jewish dictatorship by some people, and that they might even be serious, not just out to make money.

Be that as it may, according to Thomas L. Sakmyster (2012, 2) “Hungarian Jews,

who represented 5% of the population of the Kingdom of Hungary, were at the time enjoying a degree of civil equality, tolerance, and access to education that was nearly unprecedented in Europe. By the turn of the century, Jews were graduating from Hungarian high schools (the gimnázium) and universities in numbers that greatly exceeded their percentage in the population as a whole.” This, again, does not fit Csunderlik’s thesis. Indeed, in relation to Pogány, Sakmyster writes: “It was no doubt that their son would take advantage of these opportunities and rise high up from his humble family origins that prompted Vilmos and Hermina in 1896, to enroll József in one of Budapest’s most prestigious schools, the Barcsay Gimnázium. Given the meager financial resources of the family, it is probable that József received at least a partial scholarship.” (Ibid.) All this, it should be noted, occurred at a time when a large part of the Hungarian population was struggling with a shortage of work, and were emigrating to America on a huge scale. “Between 1871 and 1913, nearly 2 million Hungarian citizens emigrated overseas, mainly for economic and existential reasons. Most of them left the country in the first decade of the twentieth century,” points out Dániel Gazsó (2019, 17). It is also worth recalling here the observation of Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881) in his 1877 essay on the Jewish question. After noting that “in the whole world there is certainly no other people who would be complaining as much about their lot, incessantly” as Jews do, he concludes that “I am unable fully to believe in the screams of the Jews that they are so downtrodden, oppressed and humiliated. In my opinion, the Russian peasant, and generally, the Russian commoner, virtually bears heavier burdens than the Jew” (Dostoievsky, 1949, 640, 641). Indeed, none other than Ottó Korvin, who played an important role in the Kun regime, confirmed that his attraction to Bolshevism was motivated by something other than material benefits, or career prospects: “’I was not motivated by any material interest or desire for attention, because under the capitalist system I was able to find jobs much easier than in any Communist world order,’ he will confess later to the puzzled police chief, who, like others, sees him as a fanatic young man” (quoted in Simor, 1976, 13).

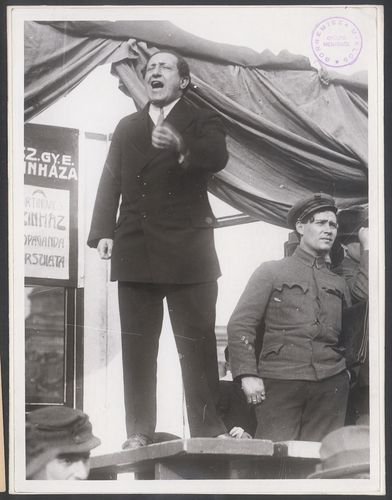

József Pogány-Schwartz, People’s Commissar, speaks at a recruitment meeting in Heroes’ Square, April 6, 1919.

József Pogány-Schwartz, People’s Commissar, speaks at a recruitment meeting in Heroes’ Square, April 6, 1919.

Further inconveniencing Csunderlik’s argument, Sakmyster points out the following:

As a young man of considerable intellectual ability and educational attainment, József Pogány had many careers open to him in the first decade of the twentieth century. With the exception of government administration and the officer corps, Hungarians of Jewish backgrounds were free to enter any of the professions, and did so in remarkable numbers. Although Jews represented only 5 percent of the population of the Kingdom of Hungary, in this period they constituted 42 percent of all journalists, 49 percent of all medical doctors, 49 percent of all lawyers, and 85 percent of all bankers. During his student days at the University of Budapest, Pogány seems to have determined that the best way to use his talents in the service of the Socialist movement, to which he had given a fervent commitment, was to become a writer. It did not take long for him to forge a successful career as a journalist with a left-wing orientation. (Sakmyster, 2012, 217)

We can conclude here, therefore, that while surely experiencing varying degrees of hostility from the general population, these highly upwardly mobile people did not, in any way, need—or have to—become pillars of a murderous regime due to “discrimination.” The alienation was certainly there, but the root of that should be explored within the realms of ethnic character and group conflict: difficulties in relating to the host nation and its culture, character, and thus passionately attempting to modify that culture, that nation, to suit their own preferences—the behavior that generated the hostility to begin with.

Despite all of this, however, Sakmyster believes that Pogány was initially fond of Hungarian culture, and it was only the hostility toward Jews during World War I (receiving some of the blame for Hungary’s losses) that alienated him from his “homeland.” This is difficult to take seriously, as anti-Jewish sentiment certainly existed before the war, but the more serious issue we face here is that, by that time, Pogány was already on the trajectory toward revolutionary—nation-transforming—Bolshevism. Worse still: Sakmyster claims that “[i]n leaving Hungary for the last time in the summer of 1919 [when the Kun regime fell] he seems to have decided that if his homeland did not want him, he would sever all ties with it” (ibid., 226). That, according to this claim, it was Pogány of all peoples, who felt betrayed and hurt by the widespread hostility of Hungarians after he just fronted a mass-murdering dictatorship, is fascinating, if true. But this again complicates the applicability of mainstream narratives about Jewish Bolsheviks seeking a kind of assimilation by removing barriers standing in the way of that process. This was, in reality, aimed at removing traditional culture and national character that were perceived as standing in the way of a renewed country, that is safer, and more comfortable, for these individuals (as Jews)—an explanation that actually is consistent with their behavior.

As we can see from all this, mainstream historians struggle to explain—or make sense of—certain aspects of Judeo-Bolshevism, resulting in self-contradictions and generally weak arguments. Refusing to accept the reality of ethnic character and its natural conflicts with differing ethnicities (on the national level, even), leads one to awkward claims like the ones above. We are also once again back to where we were with Csunderlik: if Jews like Pogány create bloody dictatorships against the out-group because the host nation partially blames their in-group for something, perhaps they never actually belonged to the nation, to begin with, and leaving is certainly a good idea. But just like with Csunderlik, Sakmyster also contradicts himself, for he claims that “[i]t was the rise of virulent anti-Semitism during and after World War I that ultimately alienated Pogány and many other Hungarian Jews of his generation. Over the years Pogány had learned to ignore the attacks that his political enemies made on him, but he could not be oblivious to the vicious campaign to blame the Jews for Hungary’s loss of the war and the humiliating peace settlement” (ibid., 225). Contrast that with “[n]or did Pogány, who would write prolifically on all of the negative aspects of bourgeois society, ever take any special interest in the problem of anti-Semitism” (ibid., 3). Perhaps he did not write about it (apart from one known instance the author cites), but seemingly did take “interest” in it if it supposedly motivated him as much as the author claims it did.

Indeed, Pogány clearly advocated for a racially mixed society: “All national, racial, and religious barriers between the proletarians must come down. Wherever there is proletarian rule, the proletarian will find a homeland, even if he speaks another language, even if he is the son of another race.” (Quoted in Chishova & Józsa, 1973, 211). The Constitution of the Kun regime stated in §14: “ The Republic of Councils does not recognize racial or national distinctions. It does not tolerate any oppression of national minorities and any restriction on the use of their language.” This is state-enforced pluralism, where even explicitly Jewish groups are protected. In the Minutes of the National Assembly of the Councils (Minutes, 1919, 258) we read that “not a shadow of doubt can be cast on the text which states that all nations [ethnic groups] living in an allied Soviet republic shall be free to use their languages and to cultivate and develop their national culture.” So the internationalist Jews who had no ethnic identity enacted legislation that would protect Jewish language and culture.

Interestingly, although there were many conflicts between Bolsheviks and Bundists, this policy is very similar to what the Jewish Bund—which has always been considered a nationalistic, Jewish type of Socialism—laid out:

[T]he Bund’s founders concluded that true internationalism must be based not on the erasure or denial of cultural and national differences but on recognition of these differences and the demand for individual and collective rights for all national minorities. Their experience as Jewish revolutionaries and trade unionists showed them that they could not depend on the goodwill of the dominant nationality, including the organized workers of this nationality, whether to defend the interests of minority workers in the present or in the democratic and socialist future. (Gechtman, 2008, 35)

As the author points out, “[t]he Bund’s national program proposed that the Russian Empire, after the democratic and socialist revolutions, must not be partitioned into a number of nation states […] but rather maintained as a multinational state where the members of every national minority (including the Jews) would enjoy equal rights as citizens as well as a limited, non-territorial form of self-government or autonomy” (ibid., 32). Bezarov (2021, 132) describes this fundamental feature of the Bund as “the self-liberation of the Jewish proletariat.”

Celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Bund in Warsaw, 1927 (source: yivoarchives.org)

Celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Bund in Warsaw, 1927 (source: yivoarchives.org)

Jewish Strategies Under the Red Flag

Although Jews were highly influential and disproportionately present in positions of power, open hostility still existed, as well as some resistance to their increase in such influence. Both the “nationalist” Jewish Bund and the Jewish Bolsheviks in Hungary (or Russia), aimed to destroy the dominance of the host nation’s traditional ethnic group over their own country, leading to easier access for them to more power within its institutions—which is precisely what happened, at least temporarily. Noteworthy here is the aim of creating, not nation-states to achieve this “autonomy,” but “multinational state[s].” Indeed, Gechtman (2008, 66) concludes that “[t]he Austro-Marxist and Bundist theories and programs developed in the early twentieth century represented a form of ‘multiculturalism avant la lettre.’ A century earlier than present-day multiculturalists, and at a time when virtually all liberals and socialists opposed the idea of collective rights for minorities within the state.” Regarding this, David Slucki (2009, 114) summarizes that the Bund “espoused a universalist understanding of Jewish life and identity that lay outside the traditional conception of the nation-state. In fact, these two ideas together served to undermine the nation-state in their call for federations of nations, which gave political and cultural power to minorities alongside the majority nations,” which would result in a “federative state that would empower all national minorities, including Jews.” This “fight for Jewish emancipation was tightly bound up with the struggle for socialism” within the Bund (ibid.). Internationalism, transnationalism, or various forms of Marx-inspired socialism effectively functioned as strategies to undermine the power of traditional nations within which Jews lived, and as such, maintaining Jewish identities, and pursuing perceived interests, is consistent with advocating internationalism.

The importance of ethnic character cannot be ignored if one is to draw accurate conclusions about instances of group conflict. It tells us something important that in Hungary it was not, say, the Germanic Danube Swabians (the Donauschwaben, who are also intelligent, urban, and upwardly mobile), or gypsies, who were so drawn to specific types of abstract expressions (through psychology and literature by psychoanalysts, or visual arts by dadaists and avant-gardists, such as the Nyolcak group, etc.), that it was not other demographics—for instance, homosexuals—who ended up forming rather cohesive revolutionary groups. Instead, it was the Jews—and so it was the Jews in many other countries in very similar ways. At the heart of the issue is, therefore, not merely minority status, urban dwelling, alienation, or discrimination, but a very specific Jewish manifestation of those, with specific aspirations. If Jews possess significantly different ethnic characteristics than, say, gypsies, then we can safely assume—indeed, observe—that their individual, as well as group-level, responses and strategies will also differ, leading to a specifically Jewish manifestation of their reaction to certain situations.

For instance, gypsies traditionally pursued a strategy of wandering around the country, and at times exploiting Hungarians, living as nomads and preferring to be left alone. Complaints about the gypsies were widespread, as Francis Wagner (1987, 35) recalled, quoting comments of publicist Kálmán Porzsolt, from the August 6, 1907 issue of the prominent newspaper, Pesti Hírlap, saying: “[A] civilized state has to exterminate this [Gypsy] race. Yes, exterminate! This is the only method.” Wagner also cites Dr. Antal Hermann, Jr., “the son of a liberal-minded, internationally famed ethnographer,” when he emphasized in a public lecture in 1913 that “[t]he nomadic life of Gypsies is full of mysticism, romanticism, stealing, burglary, kidnaping of children, animal poisoning, and murder.” These are centuries-old complaints about this group (e.g., the 1613 work La gitanilla by Miguel de Cervantes [1547–1616] contains similar complaints), and persist to this day. But these are also very different complaints than those directed at Jews (coincidentally, these millennia-old complaints have also persisted to this day, throughout ages, continents, cultures—see: Dalton, 2020; MacDonald, 2004/1998, Ch. 2). While gypsies tended to engage in that type of group-behavior, Jews were more likely drawn toward the domination and transformation of the host society through various means: whether it’s arts, psychology, politics, or sexuality… (For an examination of different diaspora peoples and their group-strategies, see: MacDonald, 2002.) Because of this tendency, early critics of psychoanalysis, for instance, noted the specifically Jewish nature that characterized their subversive activism. The words of István Apáthy, famous zoologist (and also a prominent figure of the eugenic movement) are fitting here. Sándor Ferenczi wrote to Sigmund Freud on January 29, 1914: “[Apáthy] has put himself at the head of the ’eugenic movement’ and from this position has let loose against psychoanalysis—as a panerotic aberration of the Jewish spirit.” (Freud & Ferenczi, 1993, 535) Apáthy’s complaint about the Freudian line was as follows:

Our organization, which must be shaped to serve the cause of racial health, must therefore fight with all its might against the panerotic world-conception. It must do everything in its power to persecute the race-defiling manifestations of the panerotic world-conception in literature, society, legislation and administration—for they are there—and to seek out its nests even in the scientific workshops, from which some of our doctors draw their race-corrupting moral principles, or their lack of principles. (Apáthy, 1914)

Indeed, one can observe a far-reaching fascination among young Jews for subversive, society-transforming movements, be they psychoanalysis, dadaism, avant-garde art, civic radicalism, liberalism, or any other—even Communism. Ferenczi, for example, noted in an October 30, 1919 letter to Freud, that his audience, which was extremely interested in psychoanalysis, was largely Jewish. Referring to the Galileo Circle, he wrote: “The audience was naturally composed of nine tenths Jews!” (Freud & Ferenczi, 1993, 92). This overrepresentation is a condensation of a blatant affection, so the pretense that the Bolsheviks were an atypical little group does not seem justified, as if subversive movements were not popular to any significant degree among Jews. But popular or not, if something has a certain character, it is that character that defines it.

The philosemitic discourse of mainstream “experts” therefore takes on a certain postmodern character when these historians present a Jewish Communist group, not as a Communist Jewish group, but as a Communist group of Communists, since these Jews often posed not as Jews but as the “New Soviet Man”—a globalized entity that their policies were designed to create. According to this view, when Jews were alienated by the intolerance of the host society, their Jewishness was significant, but when they formed movements, or grouped under the same umbrella because of the same alienation, their Jewishness became insignificant and they were now just “socialists” or “psychoanalysts.” This desperate avoidance of the aspect of ethnicity (both as an innate character and social identity, with all its consequences) probably stems from a desire to counter and refute “anti-Semites,” who see ethnicity as significant, and with whom these individuals would therefore find agreement repugnant. Fortunately, not everyone in the mainstream expects us to ignore the obvious.

Jaff Schatz (1991, 33) comments in his classic work on Communism in Poland:

Outside the Zionist camp, the Socialist Bund, most conspicuous in the struggle against anti-Semitism, dramatically increased its influence, despite its radical program, becoming in the second half of the 1930s the single strongest Jewish political party. The radical ideals of the Communist movement attracted a growing number of young Jews. Thus, especially among the young generation, the dark social predicament and lack of feasible perspectives produced political extremism and execeptionally [sic] high political mobilization.

Writing about “The Jewish Support for the Left in the United States,” and demonstrating the enormous Jewish involvement in it, Arthur Liebman (1976, 285) notes that “[t]he left in the United States from the pre-World War I years through the post-World War II period was in large part dependent for its survival on the support it received from persons and institutions embedded in an ethnic sub-culture—that of the Jews.” Later he adds: “The more astute and sensitive Jewish Socialists in the pre-World War I years were also careful not to place themselves and their cause at odds with all of the Jewish religion. They sought opportunities to demonstrate that Judaism, as they defined and interpreted it, was quite compatible if not supportive of socialism. Socialism was presented to the Jewish masses as a secular version of Judaism” (ibid., 291–292). Liebman also points out that “[t]he Jewish relationship to the Communist Party extended beyond that of a political organization seeking a constituency in an ethnic group. Upon examination, it becomes quite clear that in the late 1940’s the Communist Party rested upon a Jewish base. A large proportion of the membership and even more of its officials were of Jewish background,” and thus “[g]iven the majority of Jews in this group, they could not but help set a particular ethnic tone to the CP” (ibid., 306–307).

Indeed, writing about the Jewish involvement in Communism in Great Britain, Stephen Cullen (2012, 15) paints a similar picture: “It was also the case that being part of the communist movement enabled many Jews to look outside of their ghettoised existence, but not at the expense of their Jewish identity or life. Instead, key Jewish organisations, such as Jewish sports clubs and the Jewish Lads’ Brigade were essential institutions in the building of Jewish support [f]or the CPGB. In consequence, this evidence supports the contention of Srebrnik and Smith, that these communists were „Jewish Communists,” as opposed to „Communist Jews.” Henry Srebrnik proposed that “Communism thrived for a time as a specifically ethnic means of political expression, to the point where it might legitimately have been regarded as a variety of left-wing Jewish nationalism.” (Srebrnik, 1995, 136, emphasis in original)

In fact, the heavy presence of Jews in socially influential positions, and their attraction to subversive trends, generates a specifically “Jewish” problem, so even if one were to present statistics showing that the support for such in the whole of Jewry was below 50% (i.e., not the majority), this problem would still remain, especially since many of this “whole of Jewry” are not active Jews—but what proportion of active, intensive Jewry contributed directly, or indirectly, to the success of subversive movements? This is the more important question. As always, one must look at where the power of the movement derives from, and, as in all the cases described here, the power derives from activist Jews. Philosemitic and Jewish historians of the mainstream acknowledge that Jews were, indeed, heavily involved in all this. That they blame the host society for making Jews feel alienated, is beside the point.

This Jewish predominance is not only interesting from a sociological point of view, but can sometimes be of decisive importance, as it was, for example, in Russia also, as maintained by none other than the partly Jewish Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, i.e., Lenin: “Of great importance for the revolution was the fact that there were many Jewish intellectuals in the Russian cities. They liquidated the general sabotage which we had encountered after the October Revolution. … The Jewish elements were mobilized … and thus saved the revolution at a difficult moment. We were able to take over the state apparatus exclusively [исключительно] thanks to this reserve of intelligent and competent labor force — as quoted by Russian scholar of Soviet history, Gennady Kostyrchenko (2003, 58; see also: Slezkine, 2004, 225). Kostyrchenko points out that the Bolsheviks “tried to make full use of the potential for self-assertion and self-expression of Jewry, which had been so long restrained by the tsarist regime, and which contained a tremendous creative as well as destructive energy,” also adding that “the largest was the ’representation’ of Jews in the leading party bodies” (ibid., 57, 58).”

Nevertheless, some say that the Jewish element is “nonsense,” because “it is easy to show that the presence of Jews was politically unessential, be it in Poland, Hungary, or in other countries,” says Stanisław Krajewski (2000), although he does admit the “fact” that “Jews holding high official positions” were “relatively speaking, very numerous” in several countries. Krajewski admits that “I am not a historian but I am a committed Jew and I have ancestors who were communist leaders.” In light of this, it is not surprising that he also blames the host nations for the Jews’ attraction to Communism as due to alienation, discrimination, etc., and that, in his view, these Jews were guided by “noble and selfless intentions.” It is difficult to take such anxious tropes seriously when even in the context of the almost entirely Jewish Republic in Hungary, the role of the Jews is portrayed by some as irrelevant.

References

Apáthy I. (1914) A fajegészségügyi (eugenikai) szakosztály megalakulása. Magyar Társadalomtudományi Szemle 7. 2, 165–172.

Atzmon G, Hao L, Pe’er I, Velez C, Pearlman A, Palamara PF, Morrow B, Friedman E, Oddoux C, Burns E, Ostrer H. Abraham’s children in the genome era: major Jewish diaspora populations comprise distinct genetic clusters with shared Middle Eastern Ancestry. Am J Hum Genet. 2010 Jun 11;86(6):850–9.

Bezarov, O. (2021). Participation of Jews in the processes of Russian social-democratic movement. History Journal of Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University, (53), 131–142.

Carmi, S., Hui, K., Kochav, E. et al. Sequencing an Ashkenazi reference panel supports population-targeted personal genomics and illuminates Jewish and European origins. Nat Commun 5, 4835 (2014).

Cullen, Stephen Michael. “‘Jewish Communists’ or ‘Communist Jews’?: the Communist Party of Great Britain and British Jews in the 1930s.” Socialist History 12.41 (2012): 22–42.

Chishova, Lyudmila; Józsa Antal (eds.). Orosz internacionalisták a magyar Tanácsköztársaságért. Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó, 1973.

Csonthegyi Szilárd. A liberalizmus elfajzásának zsidó alapjai (I–V. részek). [The Jewish Foundations of the Degeneration of Liberalism (Parts 1–5)] Kuruc.info, February, 2024, https://kuruc.info/r/58/269970/ (Accessed: April 12, 2024)

Csunderlik Péter. Radikálisok, szabadgondolkodók, ateisták – A Galilei Kör (1908–1919) története. Napvilág Kiadó, 2017.

Csunderlik Péter: A „judeobolsevizmus vörös tengere”. Mozgó Világ, 2020. július 2.

Dalton, Thomas. Eternal Strangers: Critical Views of Jews and Judaism. Uckfield, East Sussex: Castle Hill Publishers, 2020.

Dostoievsky, Feodor M.; Boris Brasol (trans.). The Diary of a Writer. Volume Two. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1949.

Draper, Theodore. The Roots of American Communism. New York: The Viking Press, 1957.

Freud, Sigmund, Sándor Ferenczi, Eva Brabant, Ernst Falzeder, and Patrizia Giampieri-Deutsch (eds.). The Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Sándor Ferenczi. Harvard University Press, 1993.

Gazsó Dániel. A magyar diaszpóra intézményesülésének és anyaországi viszonyainak története. In: Ambrus László, Rakita Eszter (eds.). Amerikai magyarok – magyar amerikaiak: Új irányok a közös történelem kutatásában. Eger: Líceum, 2019. 15–33.

Gechtman, Roni. “A “Museum of Bad Taste”?: The Jewish Labour Bund and the Bolshevik Position Regarding the National Question, 1903–14.” Canadian Journal of History 43.1 (2008): 31–67.

Hammer MF, Behar DM, Karafet TM, Mendez FL, Hallmark B, Erez T, Zhivotovsky LA, Rosset S, Skorecki K. Extended Y chromosome haplotypes resolve multiple and unique lineages of the Jewish priesthood. Hum Genet. 2009 Nov;126(5):707-17. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0727-5. Epub 2009 Aug 8. PMID: 19669163; PMCID: PMC2771134.

Hammer MF, Redd AJ, Wood ET, Bonner MR, Jarjanazi H, Karafet T, Santachiara-Benerecetti S, Oppenheim A, Jobling MA, Jenkins T, Ostrer H, Bonne-Tamir B. Jewish and Middle Eastern non-Jewish populations share a common pool of Y-chromosome biallelic haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Jun 6;97(12):6769-74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100115997. PMID: 10801975; PMCID: PMC18733.

Kostyrchenko, Gennady Vasilyevich. Тайная политика Сталина. Власть и антисемитизм. [Stalin’s Secret Policy. Power and anti-Semitism.] Moscow: Международные отношения, 2003.

Krajewski, Stanislaw. “Jews, Communism, and the Jewish Communists.” Jewish Studies at the Central European University I. Yearbook (Public Lectures 1996–1999). ed. by Andras Kovacs, co-editor Eszter Andor, Budapest: CEU (2000): 119–133.

Liebman, Arthur. “The Ties That Bind: The Jewish Support for the Left in the United States.” American Jewish Historical Quarterly 66.2 (1976): 285–321.

MacDonald, Kevin. A People That Shall Dwell Alone Judaism as a Group Evolutionary Strategy, with Diaspora Peoples. Writers Club Press, iUniverse, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4697-9061-9. 2002.

MacDonald, Kevin. The Culture of Critique (AuthorHouse, 2002; orig. Pub. Praeger, 1998).

MacDonald, Kevin. Separation and Its Discontents (AuthorHouse, 2004; orig. Pub. Praeger, 1998)

Minutes: A Tanácsok Országos Gyűlésének naplója (1919. június 14. – 1919. június 23.). A Munkás- és Katonatanácsok gyorsirodájának feljegyzései alapján. Budapest: Athenaeum, 1919.

Nebel A, Filon D, Brinkmann B, Majumder PP, Faerman M, Oppenheim A. The Y chromosome pool of Jews as part of the genetic landscape of the Middle East. Am J Hum Genet. 2001 Nov;69(5):1095-112. doi: 10.1086/324070. Epub 2001 Sep 25. PMID: 11573163; PMCID: PMC1274378.

Need, A.C., Kasperavičiūtė, D., Cirulli, E.T. et al. A genome-wide genetic signature of Jewish ancestry perfectly separates individuals with and without full Jewish ancestry in a large random sample of European Americans. Genome Biol 10, R7 (2009).

Ostrer H. A genetic profile of contemporary Jewish populations. Nat Rev Genet. 2001 Nov;2(11):891–8.

Ostrer H, Skorecki K. The population genetics of the Jewish people. Hum Genet. 2013 Feb;132(2):119–27. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1235-6. Epub 2012 Oct 10. PMID: 23052947; PMCID: PMC3543766.

Sakmyster, Thomas L. A Communist Odyssey: The Life of József Pogány/John Pepper. Budapest. Budapest–New York: Central European University Press, 2012.

Schatz, Jaff. The Generation: The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Communists of Poland. University of California Press, 1991.

Simor András. Korvin Ottó: „…a Gondolat él…”. Budapest: Magvető, 1976.

Slezkine, Yuri. The Jewish Century. Princeton University Press, 2004.

Slucki, David. “The Bund Abroad in the Postwar Jewish World.” Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, Society 16.1 (2009): 111–144.

Srebrnik, Henry. Sidestepping the Contradictions: the Communist Party, Jewish Communists and Zionism 1935–48. In: Geoff Andrews, Nina Fishman, Kevin Morgan (eds.), Opening the Books. London: Plato Press, 1995. 124–141.

Wagner, Francis S. “The Gypsy Problem in Postwar Hungary.” Hungarian Studies Review 14.1 (1987): 33–43.