We have previously discussed extensively (here, here and here) how a decade of ultra low rates ushered in by central banks has spawned a generation of "zombie companies": corporations which under any other conditions would not survive due to their massive debt load and subpar cash creation, yet which continue to thrive thanks to ZIRP and NIRP, which make their interest expense sustainable preventing inevitable defaults, which in turn lead to subpar productivity and a general contraction in economic and corporate output.

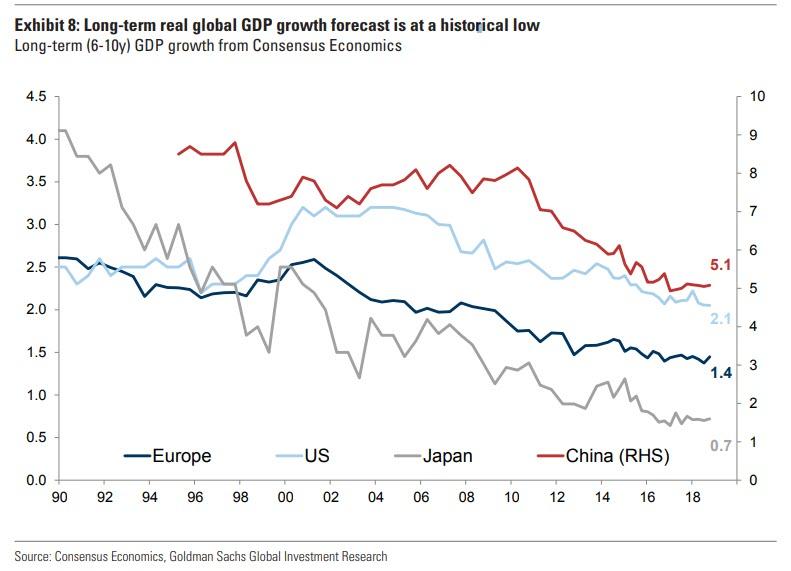

And while we won't spend more time on a topic that has been extensively dissected here in the past, we'll point out several observations from a recent presentation by Goldman which details the creeping zombification of the world, as increasingly manifest in both economic and market indicators, starting with the collapse in long-term real global GDP growth, which is now at a "historical low." Whereas much of investor focus in recent months has been on cyclical growth risks, spurred by concerns over rising interest rates, a slowing US fiscal boost, QT and US/China trade relations, Goldman's Peter Oppenheimer points out that we are already in if not growth hell, then certainly purgatory, as "there is a more important structural story on growth that is likely to have a meaningful impact on equity and asset market pricing over the medium term: trend growth has slowed."

Indeed, despite the move towards zero interest rates, the large expansion of central banks’ balance sheets and the substantial fiscal expansion in the US, the outcome has been the opposite of that desired by central banks as long-term growth forecasts have continue to decline, and as the chart below shows, this has been a fairly consistent pattern since the financial crisis. Meanwhile, actual nominal GDP has continued to weaken in the US, and even more so in Europe and Japan.

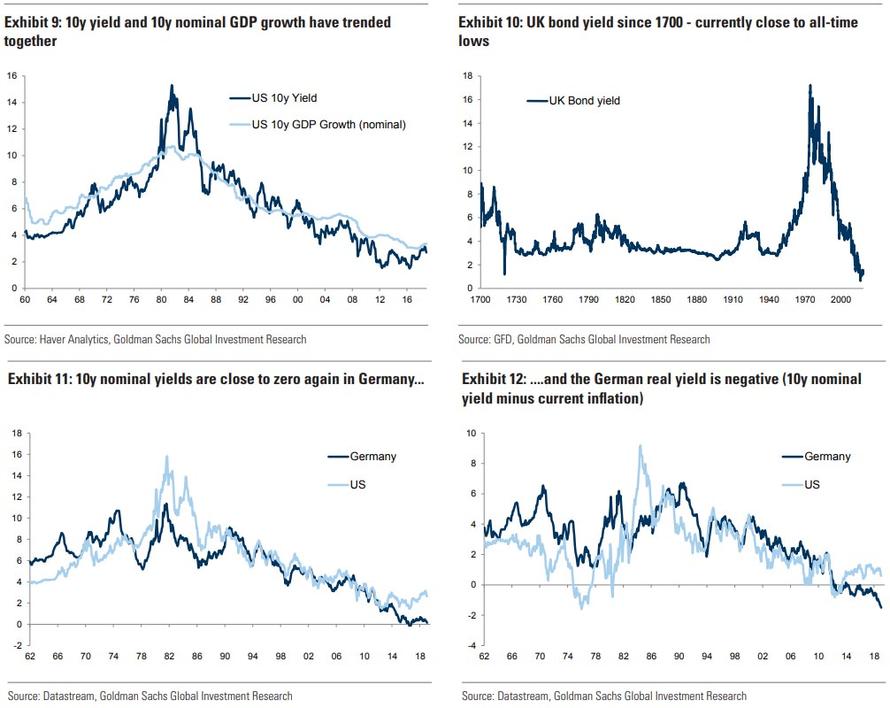

This secular decline in global growth is consistent with the message sent from interest rates, as nominal bond yields have also continued to decline despite central banks now collectively owning about a third of global sovereign debt. As Goldman notes, "in the UK, where we have a very long history, 10-year bond yields have fallen back towards record lows since the 1700s. Meanwhile, in Germany, 10-year yields have collapsed and could fall further." As a result, nominal yields back below zero cannot be ruled out – during the QE period, both 2-year and 5-year Bund yields fell deeply into negative territory.

While one can argue if the ongoing secular decline in global economic output and the increasing deflationary pressure is the result of "zombifiction" or various other reasons, such as demographics, the impact of technology, excess global saving and a fall in term premia, whatever the reasons, the trend is clearly consistent with the prospects for a long period of weak growth.

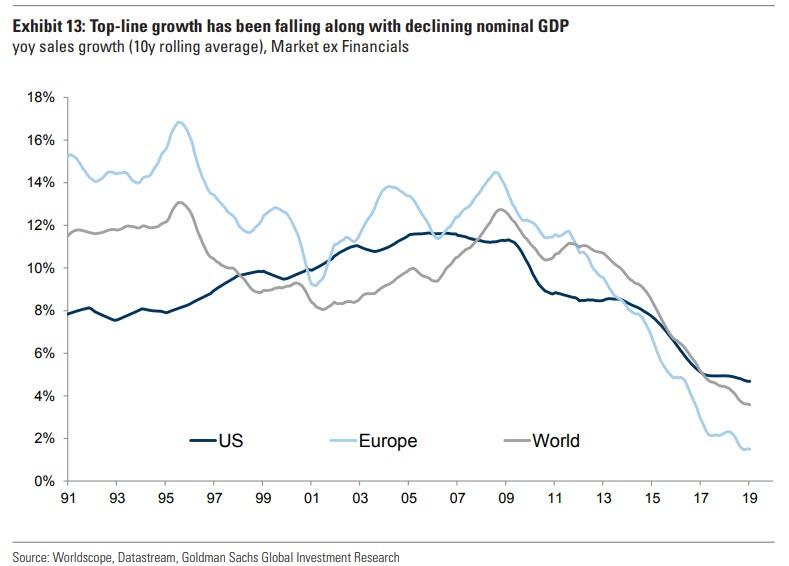

Yet one place where corporate "zombification" is quite obvious, is in the parallel drop in corporate revenue growth. Indeed, the abovementioned declines in GDP and interest rates, both nominal and real, are consistent with Goldman's recent view that "profit growth is likely to remain modest for a long time and, with it, stock returns." For the impact of low nominal growth look no further than nominal sales growth, which has not only been slowing since the financial crisis, but is now the lowest on a 10 year rolling average basis, in history (excluding the great depression).

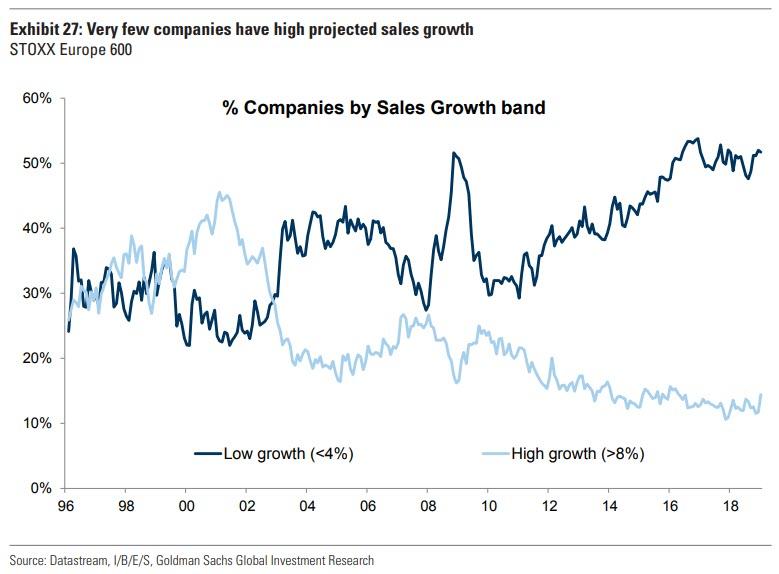

This is especially true in Europe, where one look at corporate revenue growth in just the past century shows a dramatic reversal: whereas at the start of the 21st century, high growth companies - those with revenue growth > 8% - dominated, the trend has reversed drastically in the past two decades, and as Goldman notes, there is clearly a lack of growth both economically and within the stock market in Europe, and currently the proportion of higher top line growing companies has contracted relative to those growing slowly.

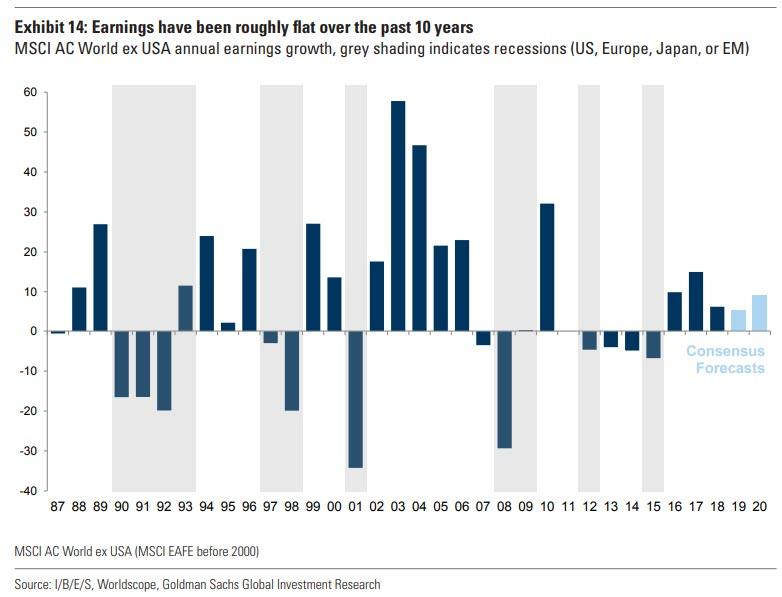

As a direct consequence of this declining economic and revenue growth, overall earnings have been weak and getting weaker. As Goldman further notes, the deep falls in profits during the financial crisis were followed by a strong rebound in 2010. But in the case of both Europe and Asia, the growth rate in earnings has stalled since then. As Exhibit 14 shows, for the World ex the US, there was a brief reprieve in 2017, when a strong synchronised global economic recovery resulted in strong earnings growth, but the bank

now expects a reversion to a period of low-single-digit earnings growth without the driver of higher valuation, which was a key driver of returns in recent years. As a result, Goldman is increasingly confident that there is little if any upside to stocks.

now expects a reversion to a period of low-single-digit earnings growth without the driver of higher valuation, which was a key driver of returns in recent years. As a result, Goldman is increasingly confident that there is little if any upside to stocks.

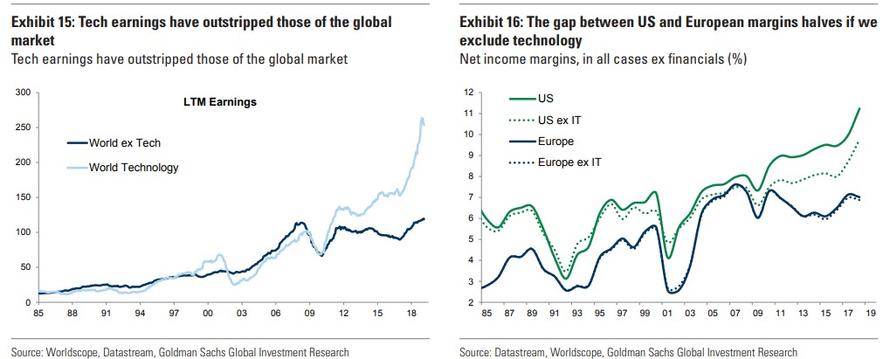

There is one silver lining to this secular growth decline: US tech stocks, which have stuck out like a clearly differentiated "thumbs up" amid a dreary "flat profits" landscape.

To be sure, a small part of why the US has been a global profit outlier can be attributed to the boom in buybacks. As Goldman explains, the earnings yield approximates the boost to EPS in excess of earnings, and has averaged 2.6% over the past 5 years. More importantly, overall profit growth has been boosted by a boom in technology earnings (Exhibit 15). Shockingly, global profits ex technology are only moderately higher than they were prior to the financial crisis, while technology profits have moved sharply upwards (mainly reflecting the impact of large US technology companies), driven by a combination of strong sales growth and sharply rising margins (Exhibit 16).

As discussed previously, much of the strong earnings growth has been a function of sharply rising margins in the technology industry. Half of the rise in S&P 500 margins since the crisis has been driven by the technology sector. As Exhibit 16 shows, the gap between US and European margins is cut in half when we exclude technology. So without such strong margins and earnings moving forward, aggregate index earnings are likely to progress more slowly. And while Goldman is still a fan of the tech sector, claiming that unlike 2000, it is not "in a bubble", at the same time, margins and revenue in this sector are unlikely to rise at the same rate going forward, which is another reason for expecting lower earnings growth and returns at the index level.

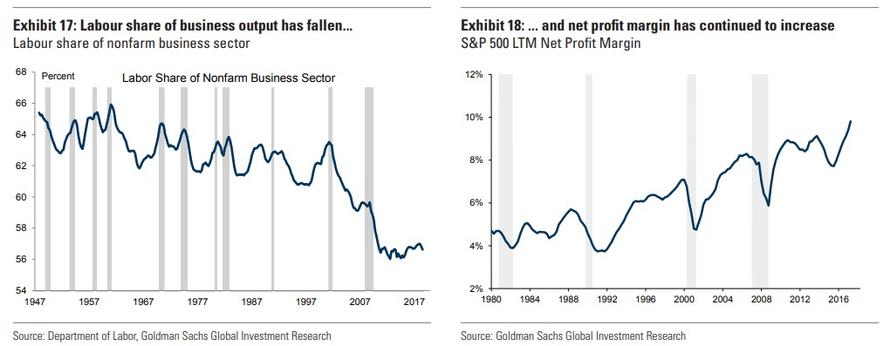

One final profit growth constraint is found in margins in general: as one would expect, profits as a percentage of GDP have risen consistently over the past two decades, supported by the impact of technology and globalization (hence the violent blowback against globalization as increasingly more people comprehend the unfair trade off between wages and shareholder gains). As a result, the future path for margins is unlikely to be as strong, for the following two reasons:

- First, tight labor markets and more populist governments could lead to higher wages; logically, the is an inverse relationship between margins and wage costs.

- Second, as mentioned above, the sharp rise in technology margins is not likely to be repeated - especially following Apple's shocking profit outlook cut- and, given higher regulatory and tax costs, are likely to come under some pressure.

What can be done to reverse these disturbing trends? The answer is simple: end the zombie companies, and allow "natural selection" among corporations and competitive capitalism to return, however for that to happen, rates will have to increase dramatically beyond the threshold that keeps most unviable companies alive currently. This is a problem because two years ago, the IMF found that some 20% of all US companies would fail if rates rise notably, a finding that was certainly noted by the Federal Reserve and is among the drivers behind Powell's recent dovish reversal. Alas, as long as central banks keep pushing on a string, keeping rates artificially low, and perpetuating the existence of "zombies", GDP, revenue, and profit growth will only continue to sink as scarce resources and capital continue to be misallocated, eventually resulting in a "Japanese" style singularity, where central banks needs to monetize all debt issuance only to prevent the financial system from imploding.