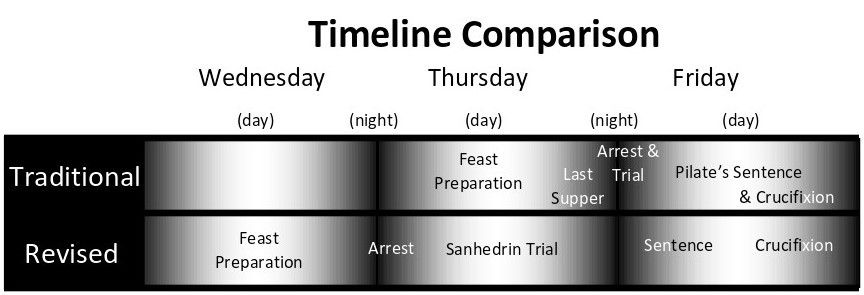

The days of Holy Week can be reconciled by careful accounting of events and by recognizing alternative ways that ancients used to mark time.

Christians around the world prepare for their Good Friday vigil by remembering the Last Supper on Holy Thursday, beginning in the late fourth century. This chronology assumes that Jesus’ trial by the Sanhedrin following his arrest at Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives commenced the night before his crucifixion.

Another debate concerns whether the Last Supper that Jesus celebrated with his disciples constituted a Passover meal. Careful aggregation of the Gospel accounts helps resolve these difficulties by linking this celebrated feast to Wednesday evening and the wee hours of Thursday morning.

Assuming the Last Supper was celebrated on Thursday evening leads to the contention that the Sanhedrin trial of Jesus occurred clandestinely that night and was thereby illegitimate. This can have misleading implications.

Elusive Target

As an itinerate healer and preacher, Jesus avoided the administrative capitals Sepphoris and Tiberius, even traveling to Phoenicia to elude Herod Antipas. (For readability, hyperlinks provide most scriptural citations.) He had no intention of being quietly slain for political exigencies, as John the Baptist had been in the Machaerus fortress as Josephus records (Antiquities §18.119).

Jewish leaders who opposed Jesus shared his objective—they sought to discredit Jesus and his ministry through a public blasphemy trial, not by a furtive Star Chamber court. They even arranged his burial as Paul related at Pisidian Antioch in c. AD 48. Hence, the traditional chronology with its nighttime forum is implausible.

Had the Sadducees merely wanted to eliminate Jesus without fuss, sicarii assassins (Ant. §20.186) could have been hired for this task, albeit at some expense. Dispatching an antagonist who frequently moved about and had worked independently as a builder—accustomed to coordinated and arduous labor—might mean an elusive and resistant target.

After a narrow escape, Jesus invited at least four fishermen as companions: Jonah’s sons Simon Peter and Andrew and Zebedee’s sons James and John, men exhibiting strength and dexterity for their vocations, able to serve as bodyguards. Nonetheless, Judas Iscariot was later paid a finder’s fee.

Paschal Sequence

Resolving this dilemma requires recognizing differences in liturgical calendars. The Johannine account identifies the “Jewish”—that is, the official—Passover, as distinct from the one celebrated by the disciples. Regarding wine, Jesus opined “the old is good,” but perhaps this also applied to the reckoning of days.

The paschal lamb is slaughtered before dusk on the 14th of the first month called “Aviv” in Cana’an, meaning between 3 p.m. and 5 p.m. at the Temple, as expounded by Josephus (War §6.423). Its carcass is roasted and consumed that evening along with unleavened bread, which would continue to be eaten over the next six days until the 21st as presented in Torah (Exodus 12:15, 13:6, 23:15 and Leviticus 23:6).

After the Babylonian conquest, the feast commenced in the evening that marked the 15th of the first month called Nisan following sight of the new moon after vernal equinox, despite prophetic objection. Josephus elucidated the eating of unleavened bread as the day succeeding the communal sacrifice (Ant. §3.248-249). Several first-century Judaic worshippers followed the pre-exile calendar based on Torah instructions (Exodus 12:2-6; Leviticus 23:5 and Numbers 9:1-3).

During Josiah’s reforms in 622 BC, Passover became a national spring feast, centralized at the place of God’s choosing. Tradition ascribes this location to Solomon’s Temple on Mount Moriah in Jerusalem. That site was destroyed in 587 BC and rebuilt by Zerubbabel in 515 BC. An earthquake in 31 BC (Ant. §15.121) led to its replacement from 20 BC (Ant. §15.388-393) through 17 BC (War §1.401) by Herod.

Despite designation of Iron Age Zion for this honor, contemporary temples to YHWH were also erected elsewhere in the Levant and in Egypt. These sites included Arad, Bethel, Elephantine Island (on the Nile), Mount Gerizim, and lastly Heliopolis.

Calendar Comparison

This festival change arose from a shift in marking the day. In the monarchical lunar calendar, days began and ended at sunrise, with the year starting in spring marked by end of visibility of the old lunar crescent.

After returning from exile in the sixth and fifth centuries BC, the priests employed another lunar calendar with days beginning and ending at sunset with the month’s beginning marked by first visibility of the new lunar crescent. Some communities, including the Essenes and Samaritans, retained the pre-exile calendar, while the community at Qumran adopted a solar calendar.

The occupying Romans used the solar Julian calendar with their days reckoning from midnight. Colin Humphreys explores these and many other details in his book “The Mystery of the Last Supper.”

Trial Hearing

Episodes following Jesus’ capture at Gethsemane seem too numerous and time-consuming to be comfortably compressed into a single Thursday evening. At his sumptuous residence, the emeritus high priest Ananus (Ant. §18.26) questioned Jesus concurrently with Peter’s denials in all four Gospel accounts (Matthew 26:70-74; Mark 14:68-71; Luke 22:57-60; and John 18:25-27).

Afterwards, Jesus was brought to the Sanhedrin for trial presided over by high priest Caiaphas, son-in-law of Ananus, who remained the most influential. Inspiration for this sacerdotal tribunal can be found in Torah and post-exilic writings. In 47 BC, Herod purged its membership (Ant. §14.175), and in AD 66 Procurator Florus informed that council of his departure (War §2.331) following the unrest he had instigated.

The proceedings against Jesus included presentation of numerous witnesses, succeeded by direct interrogation. The matter was concluded by a death sentence to be rubber-stamped shortly after by Pontius Pilate, the Roman Prefect.

Officials don’t typically operate at such breakneck expediency, even in ancient times. So when did all this happen?

Early Days of Passion Week

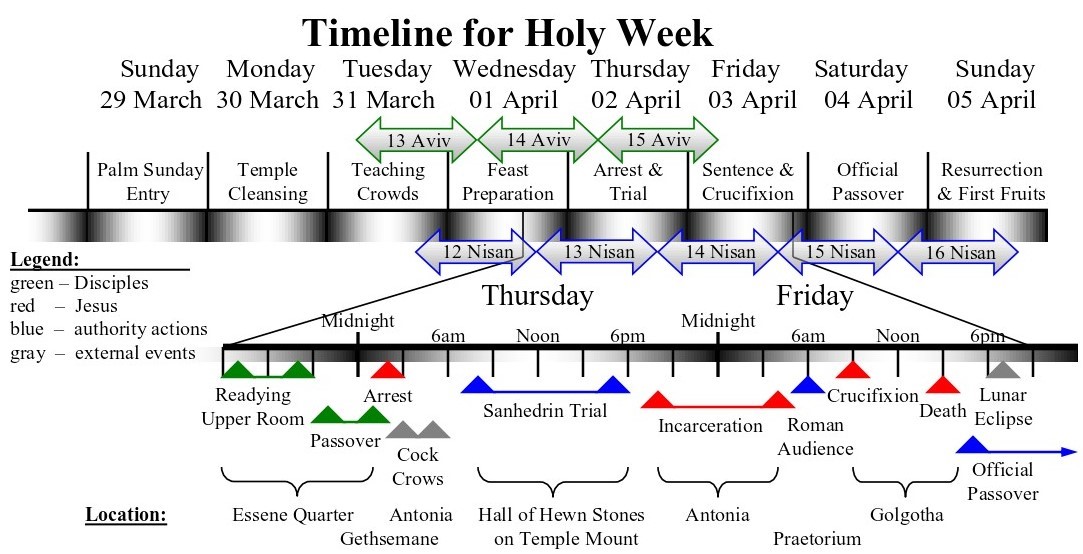

On Palm Sunday, Jesus arrived at Bethphage, counted as six days before the official Passover. His triumphal entry into Jerusalem through the Golden (or Eastern) gate (Ant. §15.424) adjacent the Temple Mount occurred that afternoon according to the Synoptics (Matthew 21:7-10 and Luke 19:37), although the Johannine account (John 12:12) indicates the day after. Based on dates for AD 33, that Sunday would correspond to 9 Nisan and 11 Aviv (in year 3793 AM) on the Hebrew calendar, which correspond to 29 March (AUC 786) on Rome’s Julian calendar.

The next day (Monday), Jesus cursed a fig tree and cleansed the Temple precinct, later departing that evening returning eastward. Unlike a similar altercation three years before, this market disruption sparked lethal reaction from the authorities.

The following day (Tuesday), the fig tree had withered, and Jesus entered Jerusalem. He taught the crowds by each Gospel account (Matthew 22:1 – 23:36; Mark 12:1-44; Luke 20:1 – 21:36; and John 12:34-36) and then departed towards evening.

The Upper Room

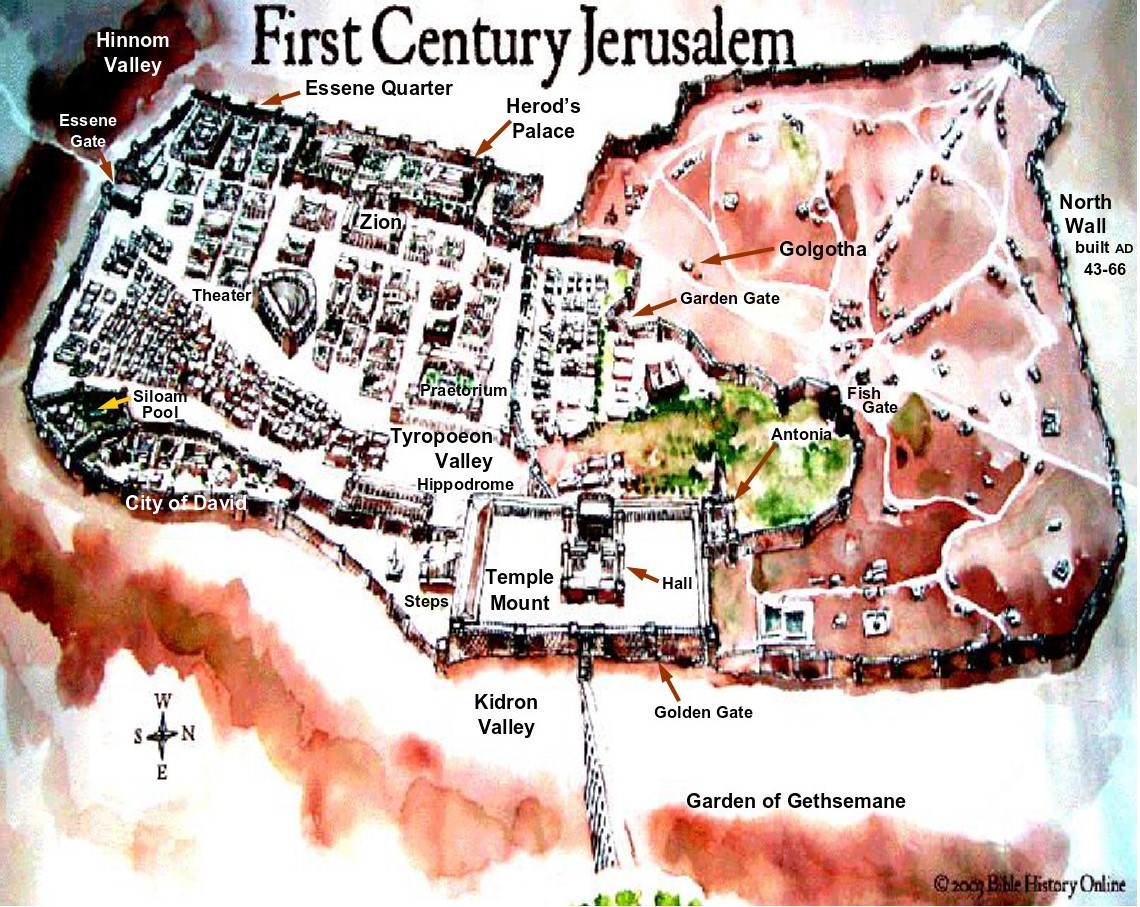

On 14 Aviv (Wednesday), Jesus instructed his disciples to find a man with a water jug and prepare the Passover feast in an upper guest room used afterward. The rendezvous likely transpired at the Siloam pool near the southern tip of the ancient City of David with a monk from the Essene community, known for their hospitality and to eschew marriage (War §2.119-121 and Pliny “Natural History” §5.73).

Such men would engage in tasks commonly relegated to women, such as carrying water. The disciples could negotiate such arrangements despite doctrinal animosity with the Herodians, so labeled from their political support of Herod (Ant. §15.377-378) c. 20 BC. That evening would mark the first day of unleavened bread that convenes the beginning of Passover.

After ritual bathing in a stepped pool called mikveh at Bethphage, Jesus and his entourage arrived at the Essene quarter in southwest Jerusalem. Before midnight, he and the disciples reclined for their communal meal for perhaps three hours while Jesus explained his Eucharistic commemoration and exhorted them at length to persevere.

Arrest and Denials

Afterward, these dozen men departed through the Essene gate (War §5.145) walking east along the Hinnom Valley, lit by the full moon as evidenced by the partial lunar eclipse in the early evening after the crucifixion some 40 hours later. Then they continued north through the Kidron Valley that flanked the ancient City of David to Gethsemane at the Mount of Olives to pray within sight of Herod’s Temple. That night Jesus was betrayed.

A crowd accompanied by Judas Iscariot approached to apprehend Jesus. They brought him to the high priest at the Antonia tower (War §5.238-241) apparently for initial questioning, probably to verify that the man seized was indeed the sought Galilean.

Peter followed into the courtyard to observe. Accused of association with the prisoner, he prevaricated. Peter’s first and third denials were succeeded first by a Roman trumpet blow at 3 a.m. of Thursday, 2 April and then according to all the Gospels, a rooster’s crowing more than an hour later (Matthew 26:74; Mark 14:72; Luke 22:60 and John 18:27) at daybreak.

Proceedings

The Sanhedrin convened at the Hall of Hewn Stones (along the Temple’s north wall) on Thursday morning of 13 Nisan (and the start of 15 Aviv) to hear testimonial attestation and then confer. The second-century judicial Midrash, Tractate Sanhedrin 4:1, requires a trial during daytime, and for a capital crime the verdict must be affirmed the following morning, procedures that probably began a century prior.

Modern confusion arises from fusing Ananus’ preliminary hearing and Caiaphas’ formal proceedings with the Gospel authors’ focus on Peter’s fear and guilt. This conflation implausibly squeezes all these incidents into only a few night-time hours.

After rendering the verdict following the hearing of witnesses and direct questioning, Jesus was handed over to guards for escorting up steps (War §5.243) and incarcerated in the Antonia for the night. Meanwhile, the council would then have notified Pilate for an audience on his judgment throne (War §2.172) at the Hasmonean Praetorium in the Tyropoeon valley a few hundred feet southwest of the Temple Mount, while his family and Tetrarch Antipas stayed at Herod’s palace (War §5.176) north of the Essene quarter. His wife’s dream suggests a judicial case would be presented the next morning, which began before 6 a.m.—the sixth hour from midnight of Friday, 3 April.

Sentence

Eventually, Pilate assented to the chief priest’s demands to fulfill the execution, corresponding to 14 Nisan – the eve of official Passover (Luke 23:54 and John 19:14, 31 that Mark 15:42 confuses with the Sabbath). Escorted from the Praetorium (rather than Antonia, as presumed since the Crusades) through the Garden gate (War §5.146) that joined outer walls, Jesus was taken outside the city onto a small hill called Golgotha to be crucified after 9 a.m., the third hour from dawn. Hanging from his cross, Jesus expired about 3 p.m., or the ninth hour, coinciding with the slaughter of Pascal lambs.

Holy Week in Review

By this reckoning, we can account for all the days of Holy Week, from Palm Sunday’s entry (29 March), Monday’s vendor eviction from the Temple courtyard (30 March), Tuesday’s fig tree observation (31 March), Wednesday’s Passover preparation (1 April), Thursday’s trial (2 April), Good Friday’s crucifixion (3 April) and Saturday’s Sabbath on the official first day of unleavened bread (4 April) with Jesus’ body in a nearby tomb. The wave offering of first fruits would begin that Sunday.

Folklore provides ritual and theological underpinnings to fill in gaps from ancient records. However, such interpretive inspirations ought not to preclude more logical and historically consistent reconstructions of transpired events. In this instance, the Last Supper can be recognized as properly belonging to Wednesday night through Thursday morning, rather than Thursday evening, whether or not religious celebrations coincide.

The Gospel accounts have been critiqued for confusing discrepancies. Despite whatever chronological deficiencies that New Testament scriveners may exhibit for their devotional emphasis in their narratives, they can’t be faulted for composing obscure fables regarding the messiah’s public ministry. Here, the times and places for the Passion narrative present a modest attempt to illuminate tradition and resolve ambiguities in sacred history from a fragmentary mosaic of secular and canonical sources.

The days of Holy Week can be reconciled by careful accounting of events and by recognizing alternative ways that ancients used to mark time. For all the superstitions ascribed to Christianity, descriptive reports such as the Passion establish its cultural context from which believers worship the God of the living. These writings thereby institutionalize the Resurrection’s historical and theological legitimacy, especially during Lent and the Easter season.