This is part of our continuing series of accounts by readers of how they shed the illusions of liberalism and became race realists.

I was born in Arizona, the second of two boys, not far from the Grand Canyon, but I have no memories of that state from childhood — my mom divorced my dad when I was two or three. As many women do after a divorce, she moved back to where her family lived, and brought the children with her. In our case, that meant Gary, Indiana — a blue-collar steel town.

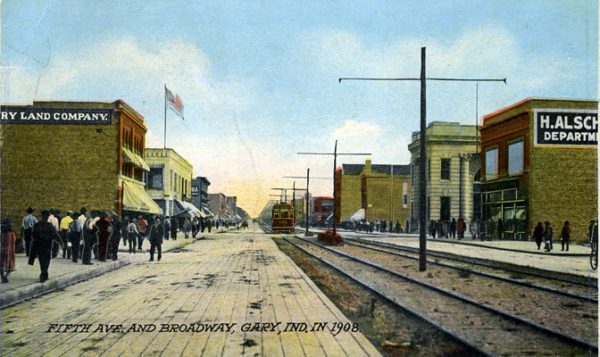

Steel was Gary’s reason for being and its number-one industry. It was founded in 1906 and named after industrialist Elbert H. Gary, who helped start U.S. Steel. He chose the site because it was close to Chicago on Lake Michigan. Gary bought a huge tract of land along the shore, which he devoted solely to steel mills. To get to the beach you have to drive to the far northeast side of the city.

Grandmother lived in downtown Gary, a few blocks from the front gates leading to the mills at the northern end of Broadway. Her husband, my grandfather, worked at the mills as an accountant, but he died before I was born. To make ends meet, Grandmother worked as a secretary at a mental-health clinic. They did not own a car; everyone walked to work in those days.

Although my grandmother was second- or third-generation American, both sides of her family were German. She knew a smattering of German and occasionally recited German-origin poems and nursery rhymes she learned as a child. How I wish I had tape-recorded some of these bits of history, or at least written them down!

When my mother divorced and returned to Gary, it was still prosperous. Mother worked as a transcriptionist at the Gary Hospital for a few years, where she met her second husband. After she remarried, she, her second husband, and we boys moved to nearby Lake Station, which was then called East Gary (its name was changed a few years later to avoid association with the declining city).

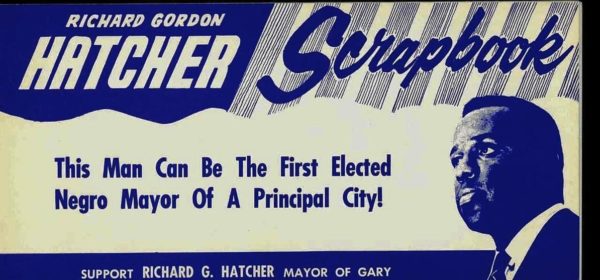

The two-and-a-half years we lived in Lake Station during the 1960s were tumultuous ones for Gary and for the nation. The broad leftward swing of politics was starting in earnest. The cultural revolution that swept the country was reflected in Gary, which elected Richard G. Hatcher as mayor — one of the first black mayors of a large American city.

Hatcher was a radical black activist, just when it became fashionable to be one. He resented whites, a sentiment he made clear during his 20 years in office. Whites fled the city, most of them settling in Merrillville, Gary’s southern suburb.

When my mother’s second marriage failed in the early 1970s and we came back to stay with Grandmother, Gary’s downtown seemed like a different place. Whites in the neighborhood were a small minority. There was one young white ne’er-do-well a few doors down from Grandmother’s house, and a couple of decent white boys around my age, but that was about it. My childhood best friend, Bobby, who had lived across the alley from my grandmother’s house, had already moved away before Mom’s second marriage. A white man of German descent owned the apartment building next door, and on the other side lived a Hispanic family with whom we got along well. Almost all our neighbors were now black.

The racial tensions were sharp. At New Jefferson school, within walking distance, where I attended third and fourth grade, my brother and I were often chased by black bullies who kept us in constant fear when school let out. There were certain neighborhoods we knew we were not allowed to go. Menacing blacks told us that a local park with a large hill — one of the few in the area suitable for sledding — was off limits.

There was a general malaise drifting over the city. There was more litter and garbage. As a kid, I thought some of Gary’s problems could be solved just by making the city look better, so in the fifth grade I started an anti-litter campaign, complete with posters that I drew myself. This was inspired by the “Keep America Beautiful” television ad campaign that was running at the time (the one with the crying Indian), but the ad that most inspired me starred a cartoon superhero called “Captain Cleanup.”

The downtown shopping district decayed gradually. I remember walking with my mom and brother downtown to go shopping, and I still have fond memories of Gary’s once-bustling shopping streets. There was Gordon’s, a somewhat upscale department store — I enjoyed riding the escalator. Sears was there, as well as JCPenney’s. Goldblatt’s, a regional department store, straddled the alley and bustled with delivery trucks.

Walgreens and Kresge’s both had lunch counters where I occasionally ate with my grandmother. Fannie May was on the ground floor of the ten-story Gary National Bank Building, along with an independently owned drugstore. There was the Palace movie theater, the Bank of Indiana (with a heated sidewalk that stayed snow-free in the winter), and Hotel Gary. Some of the side streets off Broadway were also lined with stores.

Decline started in the early 1970s and sped up as the decade progressed. People blamed the large shopping mall that opened in the white refuge of Merrillville, but that was several miles away, and the region could have supported both. The real cause, of course, was white displacement.

My brother fell in with a bad crowd and became friends with some black juvenile delinquents; he was in danger of getting into real trouble. My mother, struggling to make ends meet at her hospital job while raising two boys, called my father, who lived in Montana, and he was happy to take my brother to live with him. It was a reminder of the benefits of having two parents, even if they were divorced. Partly to keep me off the streets and out of trouble, my grandmother cleared out a room in her basement so I could have my own “clubhouse,” although I was allowed to have only one friend over at a time.

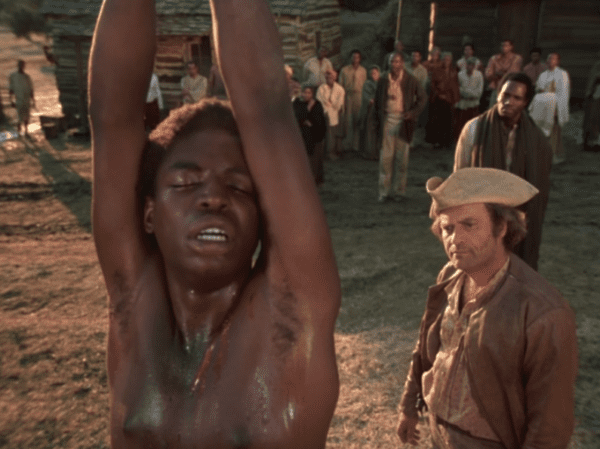

My grandmother, a Republican, had some glimmerings of racial awareness. She had a photocopy of an article from the March 30, 1969 New York Times titled “Psychologist Arouses Storm By Linking IQ to Heredity” about Arthur Jensen’s research. She showed me this article in private and talked about it in hushed tones, almost the way I imagine dissident literature was discussed in the Soviet Union. When we watched TV, my grandmother would occasionally note that if there was a criminal, he was usually white while the heroes were usually black. Once, when the miniseries Roots was being rebroadcast, my grandmother called and wrote the station to complain that constantly rehashing slavery stirred up black resentment.

I respected my grandmother. I couldn’t understand the hypocrisy of whites who carefully arranged their lives to avoid blacks, yet lectured people like her on race relations. I could understand even less the tendency to blame whites for all racial problems when, from what I could see, real racial animosity came mostly from blacks, not towards them.

My mother and I moved out to the Glen Park section of Gary while I attended junior high and high school. Glen Park was further south and closer to Merrillville. The black advance was proceeding south from downtown, but Glen Park was still mostly white and prosperous. Broadway ran through Glen Park, and there was still thriving retail there. I visited my grandmother every weekend.

Crime got worse and worse. My grandmother’s house was burgled more than once. We knew who the burglars were, because my mother saw one of them leaving the house as she was bringing my grandmother back from shopping. One of them lived down the block and across the alley. He would find out if my grandmother was home by knocking on the door to ask to borrow something. If there was no answer, he knew he was safe. When my grandmother confronted his mother, she came to Grandmother’s house to proclaim his innocence. Later, my grandma found a bag of her stolen silverware, which had obviously been dropped there by the mother.

My uncle was mugged walking down Fifth Avenue. My mother had her purse snatched. Someone pushed a gun through my grandmother’s front door when she had opened it a crack with the chain still on. She slammed the door shut and the perp ran off. One night, a rock came through my grandmother’s upstairs bedroom window. Once, when my grandmother and her sister came home by taxi, a mugger jumped them and stole their purses. My grandmother resisted and the mugger broke her arm.

I had a black friend who lived a few doors down from my grandmother. I’ll call him “William.” Since he was a bit younger than me, Mom thought he might not be a bad influence, but he kept trying to get me into trouble. I broke with him when he stole money from me.

I attended the Lutheran Church, which was on the block next to my grandmother’s house. When I graduated from first communion at age six or seven, only one of the three graduates was black, but now the membership was majority black. Once, a kindly white church lady, sensing that I was being excluded by a group of blacks, told me that someone in a minority may sometimes feel excluded and that I shouldn’t be resentful.

The white pastor led a confirmation class that included me and William. During a break, someone stole a case of soft drinks. The pastor grilled each student to find the culprit, and I couldn’t help smiling when he came to me, because his deadly seriousness struck me as ludicrous. That smile pegged me as the culprit, and no doubt his white guilt kept him from thinking any of the blacks could be responsible.

When I got home and told my grandmother what happened, she called the church and gave him a piece of her mind. Within minutes he was at her house and we had a discussion around the dining room table with my grandmother and my mother, who had taught Sunday school at the church. My grandmother told the pastor what she thought of his accusation. Finally, exasperated, he said “Will you please shut up?!” We stopped attending that church. The real perpetrator, of course, never stepped forward.

Gary’s downtown continued to decline, and one store after another was boarded up, never to be reoccupied. A jewelry store, which had been there for 26 years, was one of the first to leave. There had been repeated break-ins and blacks threatened the owner several times at gunpoint. Gordon’s department store and the Palace Theater closed in 1972, Sears in 1975, the State Theater in 1977, and Goldblatt’s in 1981. Meanwhile, Highway 30 in mostly-white Merrillville, grew as a retail hub. The full blocks of unoccupied stores along Broadway became an attraction for urbanologists, who studied them for documentaries on how buildings decay when they are neglected for decades.

Many other notable buildings were lost. The Tivoli Theater on Fifth Avenue near my grandmother’s house, which had a terra-cotta façade dominated by a massive rosette stained glass window, was torn down. Gary had benefited from its proximity to Chicago, an architectural hub, and boasted buildings by notable architects. My grandmother lived in a house — one of several in the city — built with an innovative method of poured concrete, commonly credited to Thomas Edison. Although it was a modest workingman’s home, it had hardwood floors, a cast-iron fireplace, a small pantry area, a built-in china cabinet with cut-glass doors, and central heating.

Even as a teenager, I saw that blacks had little appreciation for historic architecture. The oldest, most distinctive homes were the most likely to be neglected and abandoned.

The decay continued to spread into Glen Park towards Merrillville. The basement apartment where my mother and I lived in Glen Park was burgled. During a school-bus strike, I had to ride my skateboard home from school, since bicycles were stolen even when they were chained up. I was menaced by a black who didn’t think I should be in his neighborhood. More and more Glen Park businesses closed.

The city buses were used as school buses. Students dropped coins into the fare box when they boarded, just like on any other bus, and one of the black drivers held his hands over the coin slot, taking the money for himself. None of the black students had any objection to this, but I reported it. I was about the only white on the bus, and I was immediately suspected of being the “rat.”

My high school in Glen Park was about 25 percent white, 60 percent black, and 15 percent Hispanic. One night, someone broke into the school and set fire to the library. Firefighters rescued the building, but students were deprived of a library and the auditorium above it for two-and-a-half years.

Not all my experiences with blacks were bad. A black English teacher in junior high was my favorite. He was an accomplished amateur magician, and he let me perform a ventriloquist act as the opener for his yearly magic show in the auditorium. Because I drew a comic strip for four years for the high-school newspaper, I was inducted into the gifted and talented program, where I studied under the black cartoonist for the Gary newspaper. However, I never had any really close black friends. There was an insurmountable wall of differences and resentments between whites and blacks — and to a lesser degree Hispanics — that made true friendship impossible.

My grandmother moved when I graduated from high school, perhaps barely in the nick of time. One night, when I was staying at her house, I heard bangs I thought were firecrackers. When I woke up the next day, I learned there had been a shootout in the garage behind the next-door apartment building. My grandmother moved into the renovated Hotel Gary, which had become a retirement home and renamed “Genesis Towers.”

My father, a college professor (with liberal politics to match), told me about a college with a work-study program for poor people in the Appalachian region. I applied and was accepted. It turned out the college was founded by a white abolitionist minister as one of the first integrated colleges in the region, but it was about 90 percent white — a breath of fresh air after Gary. I was subjected to a certain amount of indoctrination. Alex Haley, author of Roots, spoke at a convocation and was named honorary dean. I thought he wasn’t such a bad guy and was a little embarrassed that my grandmother had complained about his miniseries. Years later, I learned Haley had plagiarized much of his novel.

Time passed, and after the 9/11 attacks, I became more interested in world politics. Reading an article on all the problems in Africa prompted me to Google “Why Is Africa Poor?” and it led me to an article by William Robertson Boggs in the American Renaissance archives with that very title (that was back when Google still took you to AmRen articles). The article explained a lot, not only about Africa, but about what happened to Gary. I read every article in the archives and have been a daily AmRen reader ever since.

If you have a story about how you became racially aware, we’d like to hear it. If it is well written and compelling, we will publish it. Use a pen name, stay under 1,200 words, and send it to us here.

https://www.unz.com/article/i-became-a-race-realist-growing-up-in-gary-indiana/