Our real-world experience tells

us the official inflation rate doesn't reflect the actual cost increases of

everything from burritos to healthcare.

In our household, we measure

inflation with the Burrito Index: How much

has the cost of a regular burrito at our favorite taco truck gone up?

Since we keep detailed

records of expenses (a necessity if you’re a self-employed free-lance writer),

I can track the real-world inflation of the Burrito Index with great accuracy:

the cost of a regular burrito from our local taco truck has gone up from $2.50

in 2001 to $5 in 2010 to $6.50 in 2016.

That’s a $160% increase since 2001; 15 years in which the official

inflation rate reports that what $1 bought in 2001 can supposedly be bought

with $1.35 today.

If the Burrito Index had

tracked official inflation, the burrito at our truck should cost $3.38—up only

35% from 2001. Compare that to today's actual cost of $6.50—almost double what

it “should cost” according to official inflation calculations.

Since 2001, the real-world

burrito index is 4.5 times greater than the official rate of

inflation—not a trivial difference.

Between 2010 and now, the

Burrito Index has logged a 30% increase, more than triple the officially

registered 10% drop in purchasing power over the same time.

Those interested can check

the official inflation rate (going back to 1913) with the BLS Inflation

calculator by clicking here.

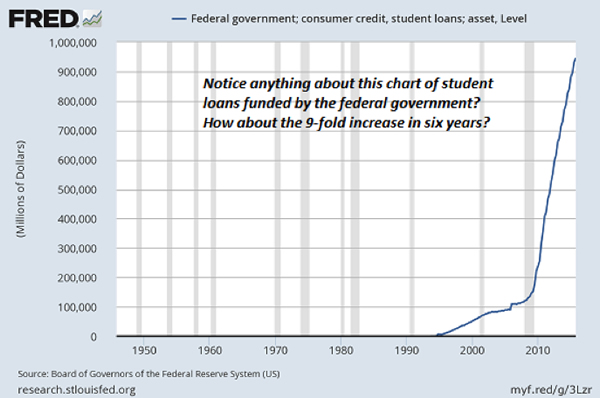

My Burrito Index is a rough-and-ready index of real-world inflation. To

insure its measure isn’t an outlying aberration, we also need to track the

real-world costs of big-ticket items such as college tuition and healthcare

insurance, as well as local government-provided services. When we do, we

observe results of similar magnitude.

The takeaway? Our

money is losing its purchasing power much faster than the government would like

us to believe.

Comparing Burritos to Burritos: A Staggering Divergence of Reality and

Official Inflation

According to official statistics,

inflation has reduced the purchasing power of the dollar by a mere 6% since

2011: barely above 1% a year. We’ve supposedly seen our purchasing power

decline by 27% in the 12 years since 2004—an average rate of 2.25% per year.

But our real-world experience

tells us the official inflation rate doesn’t reflect the actual cost increases

of everything from burritos to healthcare.

The cost of a regular taco

was $1.25 in 2010. By official standards, it should cost a dime more. Oops—it’s

now $2 each, a 60% increase, six times the official rate.

The cost of a

Vietnamese-style sandwich (banh mi) at our favorite Chinatown

deli has jumped from $1.50 in 2001 to $2 in 2004 to $3.50 in 2016. That

$1.50 increase since 2004 is a 75% jump, roughly triple the official 27%

reduction in purchasing power.

So let’s play Devil’s

Advocate and suggest that these extraordinary increases are limited to “food

purchased away from home,” to use the official jargon for meals purchased at

fast-food joints, delis, cafes, microbreweries and restaurants.

Well, how about public

university tuition? That’s not something you buy every week like a burrito.

Getting out our calculator, we find that the cost for four years of tuition and

fees at a public university will set you back about 8,600 burritos. Throw in

books (assume the student lives at home, so no on-campus dorm room or food

expenses) and other college expenses and you’re up to 10,000 burritos, or

$65,000 for the four years at a public university.

University of California at Davis:

2004 in-state tuition $5,684

2015 in state tuition $13,951

2015 in state tuition $13,951

That’s an increase of 145% in a time span in which official inflation

says tuition in 2015 should have cost 25% more than it did in 2004, i.e.

$7,105. Oops—the real world costs are basically double official

inflation—a difference of about $30,000 per four-year bachelor’s degree per

student.

Here’s my alma mater (and no,

you can’t get a degree in surfing, sorry):

University

of Hawaii at Manoa:

2004 in-state tuition: $4,487

2016 in-state tuition: $10,872

2016 in-state tuition: $10,872

Sure, some public and private

universities offer tuition waivers and financial aid to needy or talented

students, but the majority of households/students are on the hook for a big

chunk of these costs. And remember that many students are paying living

expenses, which doubles the cost of the diploma.

If you think I cherry-picked

these two public universities, check out this article:

So the divergence between

real-world costs and official inflation isn’t limited to burritos; it’s just as

bad in items that cost tens of thousands of dollars.

The Official Fantasy of Hedonic

Adjustments

In the official calculation

of inflation, hedonic adjustments offset soaring costs:

that 160% increase in the cost of a burrito is offset by the much lower cost

for computers, especially when the greater processing power and memory are

accounted for.

Clothing has also gotten

cheaper, and this theoretically offsets higher costs elsewhere.

The problem with this is sort

of calculation is that we have to eat every day and we have to pay higher

education costs if we want our kids to remain in the middle class, but we only

buy a new “cheaper” computer once every few years, and we don’t even have to

buy new clothing at all, given the proliferation of used clothing outlets, swap

meets, etc. (I do my annual clothing shopping at Costco: two pair of jeans for

$15 each , one pair of shoes for $15, etc.)

The savings on $100 of new

clothing per year or a $600 computer every three years does not offset the

doubling or tripling of costs for items we consume daily or big-ticket essentials

such as higher education, rent and healthcare.

Official Inflation: A Flawed

Metric

Official inflation also

assumes that consumers will actively substitute a cheaper alternative for

whatever is soaring in price. If a burrito doubles in cost, then the consumer

is supposed to buy a banh mi sandwich instead.

(Oops, that doubled in price, too. So much for substitution gimmicks.)

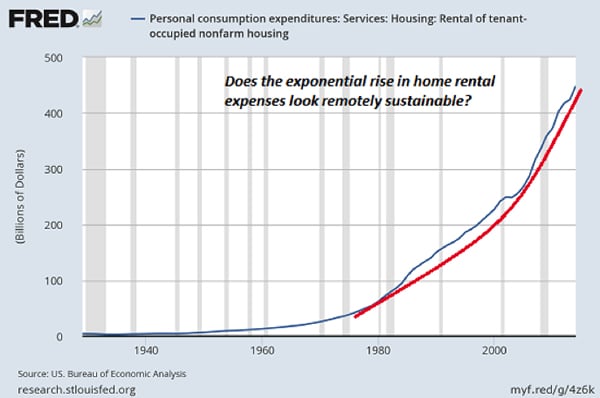

The problem is pretty obvious: there

are no alternatives for big-ticket essentials. There is no “cheaper” substitute

for a four-year public university diploma or meaningful healthcare insurance.

There is also no alternative to renting a roof over your head if you can’t

afford to buy a house (or don’t want to gamble in the housing-bubble casino).

The scale of the costs matters. If

I bought a burrito every working day (5 per week, with two weeks of vacation

annually) for four years, that’s 250 per year or 1,000 burritos over four

years. That’s one-tenth the cost of a university degree—assuming I can get all

the classes needed to graduate in four years.

I can always lower the cost

of lunch by making a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich at home rather than

buying a burrito for $6.50, but there are limited ways to reduce the cost of a

public university, which is already the “cheaper” alternative to private

universities.

Even stripped-down healthcare

insurance has soared in multiples of the official inflation rate.

Inflation in big-ticket items

adds up to tens of thousands of dollars—costs that can’t be offset by choosing

a cheaper mobile phone, cheaper clothing or substituting a peanut butter

sandwich made at home for a burrito at the taco truck.

Even if you skip buying lunch

for four years, you’ve only offset 1/10th of

the cost of a university diploma, a four-year stint in which the student lives

at home and also eats peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches every day for four

years (at least in in our barebones example of books, tuition and fees only, no

dorm or university-provided food expenses).

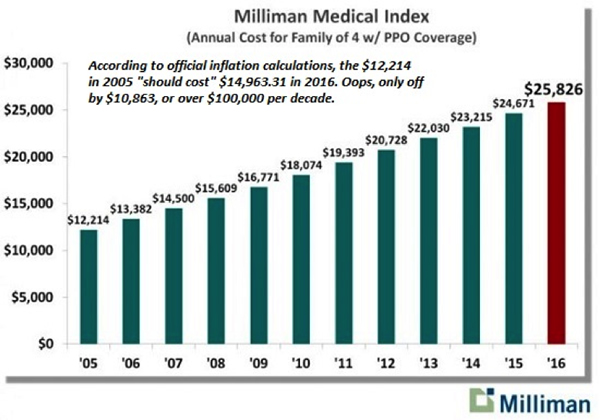

As for healthcare: feast your

eyes on this chart of medical expenses.

According to official

inflation calculations, the $12,214 annual medical costs for a family of four

in 2005 “should cost” $14,963 today in 2016.

Oops—the actual cost is

$25,826, $10,863 higher than official inflation, which adds over $100,000 in

cash outlays above and beyond official inflation in the course of a decade.

So let’s add the $30,000 per

university student above and beyond inflation for two college students over a

decade and the $100,000 in healthcare costs that are above and beyond inflation

over that decade, and we get $160,000.

Since deductions for

education and healthcare don’t completely wipe out income taxes, the household

has to earn close to $200,000 more over the decade to net out the $160,000 to

pay typical college and healthcare costs above and beyond what education and

healthcare “should cost” if inflation in big-ticket items had actually tracked

official inflation.

$100,000 here, $100,000 there and

pretty soon you’re talking real money in a nation in which

median household income is around $57,000 annually.

So if a household’s income kept

up with official inflation over a decade, that household would have to earn at

least $20,000 more per year just to keep pace with real-world,

big-ticket cost increases.

That’s the problem, isn’t it? If

the household’s wages only kept up with inflation, there isn’t another $20,000

a year in additional income needed to pay these soaring big-ticket costs. So the shortfall

has to be borrowed, burdening the household with debt and interest payments for

decades to come, or the kids don’t attend college and the household goes

without healthcare insurance.

I’ve done some real-world apples-to-apples

calculations on our household’s costs of healthcare insurance,

which we buy ourselves without any subsidies because we’re self-employed and we

earn too much to qualify for ACA/Obamacare subsidies. (I would have qualified

easily for the subsidies due to low earnings for the 20 years prior to

Obamacare, but weirdly, as soon as ACA passed my income increased. Go figure.)

We’ve bought our

stripped-down healthcare insurance from one of the more competitive non-profit

providers, Kaiser Permanente, for the past 25 years. We’ve had the same plan

(no meds, eyewear or dental coverage, and a $50 co-pay for any visit) for the

entire quarter century. (Our plan is now grandfathered; the ACA equivalent is

more expensive.) To keep the comparisons apples-to-apples, I compared identical

coverage for the same-age person from year to year.

In 1996, the monthly cost to

insure a 43-year old was $95. Now, the same plan for a 43-year old is $416 per

month—more than four times as much for the same coverage. If the costs

had risen only in line official inflation, (52% since 1996), the monthly costs

would be $145, not $416.

The cost of insurance for a

55-year old in 2008 was $325 per month. Today, the same plan for a 55-year old

is $558, a 72% increase over a time span that officially only logged an 11%

increase in inflation.

Last but not least, let’s

look at a government-provided service—weekly trash pickup. Since 2011,

our trash fees have gone up 34.5%, compared to the official reduction in

purchasing power of 6% since 2011.

Once again, real-world costs

have soared at a rate that is almost six times higher than the official rate of

inflation.

The reality is real-world inflation in big-ticket essentials is

crushing every household that doesn’t qualify for government subsidies of

higher education, rent and healthcare.

In Part 2: How To Beat Inflation,

we examine a number of strategies for offsetting the soaring costs of

everything from burritos to healthcare -- with particular focus on the

investments and actions you can take today, inside and outside of the markets,

to preserve the purchasing power of your wealth from the

nefarious "stealth tax" placed on your money by the kind of

inflation discussed above.

Click here to read Part 2 of

this report (free executive summary, enrollment required

for full access)

This essay was first published

on peakprosperity.com,

where I've been a contributing writer for many years.