If you want to feel your head swim, consider this awe-inspiring fact. When Christ was born two thousand years ago, the Great Pyramid at Giza was already more than two thousand years old. In fact, the Great Pyramid is about 4500 years old. But reproducing it would challenge — and perhaps defeat — the technology and organization of modern America or Britain. It’s the worthy structure that begins a fascinating and enjoyable book called Great Buildings (2012), whose subtitle promises The World’s Architectural Masterpieces Explored and Explained.

Great Buildings, a fascinating book that says much more than it intends to

The book was written by an English architectural historian called Philip Wilkinson and belongs to the often excellent Dorling Kindersley series of large-format surveys of history, technology and science. But the book does much more than its author and publisher intended, because it implicitly supports some heterodox and even heretical ideas about politics, culture and human biological difference. When he’s presenting dates of construction, Wilkinson uses “BCE” and “CE,” the supposedly inclusive but actually anti-Christian and anti-Western abbreviations that stand for “Before Common Era” and “Common Era.” Those abbreviations were invented by Jewish academics to replace “BC” and “AD,” meaning “Before Christ” and “Anno Domini” (in the year of Our Lord). In other words, these Jews wanted to push Christ and Christianity out of history. They have succeeded getting their terminology adopted by mainstream publishers, and it has been eagerly adopted by the left generally. It’s one apparently small but in fact very significant expression of leftists’ hatred of Western civilization and their longing to dominate it, destroy it, and rule the ruins.

Man-made mountain — the Great Pyramid at Giza, c. 2500 BC (image from Infogalactic)

By adopting that anti-Western chronology, Wilkinson and his publisher reveal their own leftism. But the book they created is an implicit repudiation of leftist dogma on the oneness of humanity. Large buildings have always been the clearest and most obvious examples of what German might call Kulturgeist, that is, culture-spirit or the expression of the unique traits and abilities of a particular culture. But a culture-spirit is ultimately a race-spirit, an expression of the genetically influenced abilities and preferences of a particular racial group. And once it is complete, a pyramid or a cathedral or a temple becomes a central part of culture-gene interaction: it creates an environment in which members of a particular race can feel happy, energized, positive about themselves and their future, prepared to invest in and work for posterity. Great Buildings is, in effect, a tour of different race-spirits and the different ways in which genetically distinct groups of human being have constructed buildings to suit themselves, strengthen their culture, and attempt to secure the survival of their civilization.

Angkor Wat and Chartres Cathedral (images from Infogalactic)

Angkor Wat and Chartres Cathedral (images from Infogalactic)

And what has suited human beings in their architecture throughout almost all of history has been the combining of beauty and grandeur. In their racially distinct ways, the temple-complex (c. 1150 AD) at Angkor Wat in Cambodia and Chartres Cathedral (1194–1223 AD) in France both pursue that goal. But you could say that Angkor Wat is chthonic and Chartres is astral. Angkor Wat seems to grow out of the earth and seems to remain deeply rooted there. Chartres aspires to escape the earth, to draw the mind and spirit heavenward to dwell among the stars.

But there are also distinctive architectural traditions within the West. The Palatine Chapel in Aachen, Germany, and the Borgund Stave Church at Lærdal, Norway, are brother-buildings, but are different in more than simply their choices of building-material. The Palatine Chapel, built in stone, is part of Roman tradition; the Borgund Stave Church, built in wood, is Scandinavian. Both are Christian, both are beautiful, both are rooted in paganism. But they’re distinct and affect the eye and mind in different ways.

The Palatine Chapel and the Borgund Stave Church (images from Infogalactic)

The Palatine Chapel and the Borgund Stave Church (images from Infogalactic)

That is, after all, the central role of architecture: to celebrate and affirm the spirit of a particular culture, its gods and its history. Or at least, that was the central role of architecture. Great Buildings does something else that its author and publisher did not intend: by presenting so many centuries of great architecture so well, it underlies the radical — and repulsive — nature of a grand discontinuity that struck the Western world in the twentieth century. You could say that the book begins with a man-made mountain and ends with merde maximale — a maximal shit from the present day. The Great Pyramid at Giza is a man-made mountain and the merde maximale is the work of modernist architects like Frank Gehry (born 1929) and Zaha Hadid (1950-2016). Gehry is Jewish and designed the appallingly ugly, obtrusive and eye-assaulting Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, which displays ugly modernist art under the auspices of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, as set up by the Jewish plutocrat Solomon R. Guggenheim (1861-1949).

Gehry’s grotesque Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (image from Infogalactic)

I think the Jewishness and the ugliness of the building and its contents are related. Until it reaches the section entitled “1900 to Present,” Great Buildings displays and discusses glorious architecture inspired by major world religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity and Islam. One religion is conspicuous by its absence: there was no glorious architecture inspired by Judaism. But you could say that modern architecture is inspired by Judaism — Jewish values, Jewish ideas, Jewish money. And that’s why architecture has descended from the sublime to the repulsive.

The invention of Jewish genius

You can see the same descent and same discontinuity in books about the history of art. Before the twentieth century, art was sublime; during the twentieth century it turned repulsive. Modernist art-movements like Dadaism assailed traditional standards of beauty and meaning, and abandoned traditional requirements for artistic competence and realism. Brenton Sanderson has exposed the Jewishness of Dada in his article “Tristan Tzara and the Jewish Roots of Dada.” He’s also discussed — and demolished — the work of the Jewish “genius” Mark Rothko (1903-70), one of the supreme exemplars of the abandonment of artistic competence. When goy philistines say “My six-year-old could have painted that” of a Rothko painting, they’re usually quite right. But one of the great advantages of abandoning artistic competence and realism, from the Jewish point of view, was that it enabled power to pass from gentile artists to Jewish art-critics and art-dealers, who were then able to promote (and profit from) Jewish “geniuses” like Rothko and Marc Chagall.

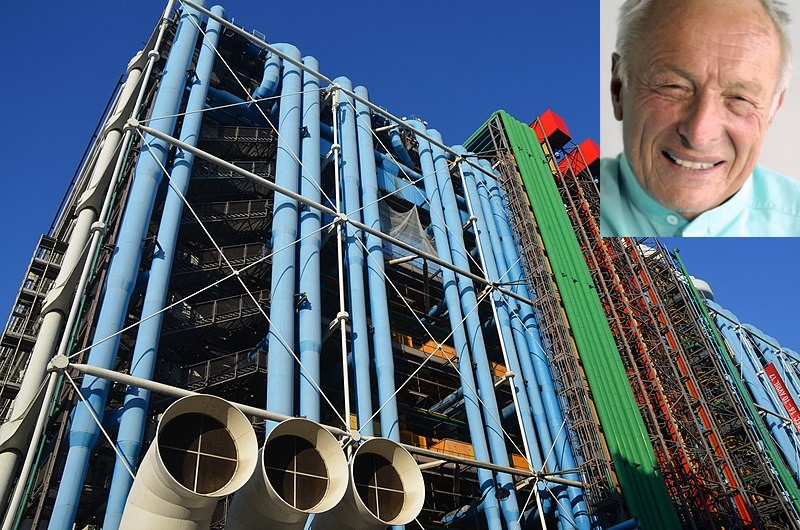

“Mensch” Richard Rogers and his architectural evisceration, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris (images from Wikipedia)

Alas, unlike art, architecture isn’t suited for the stripping away of all competence and technical ability. Even Jewish architects have to be able to design buildings that stand up, resist the elements, and refuse to collapse in all but the most extreme circumstances. But modern architects don’t have to be able to design buildings that delight the eye and elevate the spirit. Indeed, they’re now trained to design buildings that do the opposite: dismay the eye and depress the spirit. According to Great Buildings, the “prestigious Pritzker Prize” is “architecture’s highest honour.” It was established by the Jewish plutocrat Jay Pritzker (1922-99) in 1979 and has been awarded to atrocity-mongers and uglifiers like the Jewish Richard Rogers (1933-2021). Rogers was saluted as “a mensch of an architect, full of whimsy, genius and morality” by the Jewish Forward magazine on his death in 2021. Well, I would describe his acclaimed Pompidou Centre not simply as an architectural abortion but as an architectural evisceration. The viscera of the building — its pipes and ducts and elevators — have been strewn over its exterior. It’s a supremely ugly and uninspiring spectacle. Naturally enough, it’s hailed as a masterpiece of modernism.

Merde MAXXImale: Zaha Hadid and her MAXXI Museum in Rome (images from Wikipedia)

Merde MAXXImale: Zaha Hadid and her MAXXI Museum in Rome (images from Wikipedia)

The “prestigious Pritzker Prize” was also awarded to Zaha Hadid (1950-2016), a lavishly praised female architect who embodied the ugliness of modernism and the catastrophic decline of architecture in more ways than one. She was personally ugly and Great Buildings describes her as “Iraqi-British.” That is, she was an Iraqi Muslim who first took a mathematics degree in Beirut before studying architecture in London. She then went on create horrors like the MAXXI, a museum of modern art in Italy. Perhaps Hadid learnt French during her studies in Beirut and would have understood me when I call the museum merde MAXXImale — “MAXXImal shit.” If so, she would also have understood the ominous words of the French modernist Le Corbusier (1887-1965): “Une maison est une machine à habiter.” Great Buildings translates those words into English: “A house is a machine for living in.” Le Corbusier was a gentile but was one of the greatest proponents of uglification in architecture. Hadid certainly made his principle central to her work. Like those of so many modernists, her architectural abortions look like kitchen utensils or household appliances reproduced on a gigantic scale in concrete and steel.

Miracle in marble: the Taj Mahal in India

Miracle in marble: the Taj Mahal in India

In giving so many archi-abortions to the world, the Muslim-born Hadid broke with a glorious Islamic tradition of beautiful architecture. For me, the greatest building of Great Buildings is the Taj Mahal, the “vision of shimmering white marble” erected by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (1592?-1666) near the river Yamuna in northern India. Like Christianity but unlike Judaism, Islam has given great beauty to the world in its art and buildings. Chartres Cathedral, a Christian masterpiece included in Great Buildings, rivals the Taj Mahal for beauty but does not match it, in my opinion. One reason for that is that the Taj Mahal incorporates an element of beauty that was far less developed in the Christian world: calligraphy. Indeed, as Great Buildings points out, only one identity is certain among the myriad craftsmen who worked on the Taj Mahal, that of the Iranian calligrapher Amanat Khan, who embellished the Taj Mahal with quotations from the Qur’an in an alternately sinuous and sword-like script.

A giant open-air urinal

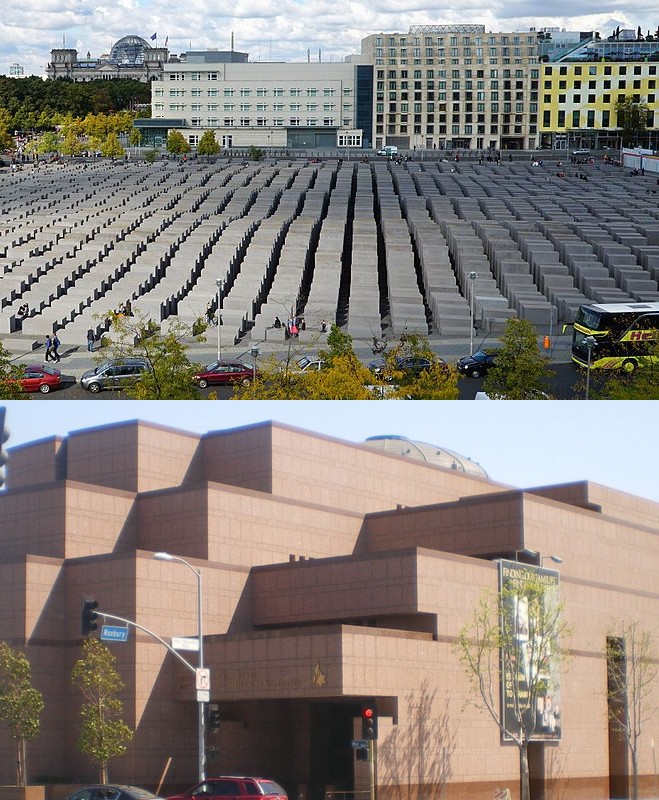

Khan’s calligraphy is, perhaps, the final touch that brings the Taj Mahal as close to perfection as any building has reached. Islam does not belong in the West, but has given the world some truly beautiful architecture. Judaism is many centuries older than Islam and has given the world no beautiful architecture. Indeed, Jews have responded to the ethical atrocity of the Holocaust by inflicting aesthetic atrocities of their own on the world, like the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin and the so-called Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles.

Aesthetic atrocities: the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin and the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles (images from Wikipedia)

Fortunately enough, neither of these horrors appears in Great Buildings. The author and publisher may have been anxious to placate Jews by including the dreck of Rogers and Gehry, but they didn’t want to take sycophancy too far. The Memorial in Berlin looks like a giant open-air urinal and the Museum of Tolerance like a post-modern public lavatory in fetching fecal shades. Perhaps the appearance of the Memorial and the Museum is a private Jewish joke about “taking the piss” and “peddling shit.” What’s certain is that Jews don’t mind commemorating the Holocaust with very ugly architecture that is completely lacking beauty and grandeur. However, Jews themselves don’t lack something that is, in fact, more important in architecture than a love of beauty and grandeur. That something is implicit on every page of Great Buildings, whether the book is discussing the Parthenon in Greece or the Temple of the Inscriptions in Mexico.

Is it coincidental that Islam produced both beautiful calligraphy and beautiful architecture, while Judaism produced neither? It’s not a coincidence at all, I would say. The same beauty-loving spirit inspired calligraphy and architecture in Islam, but there was no such spirit in Judaism. However, Jews don’t lack something that is, in fact, more important in architecture than a love of beauty and grandeur. That something is implicit on every page of Great Buildings, whether the book is discussing the Parthenon in Greece or the Temple of the Inscriptions in Mexico.

/https://contest-public-media.si-cdn.com/02deab07-c044-46e5-b958-f5d28173d2ed.jpg)

Replication of the Parthenon in Nashville Greece (top) and the Temple of the Inscriptions in Mexico

And what is that something? It’s intelligence. Building big demands brain-power. Great Buildings doesn’t discuss this stark biocultural fact, but it’s the one thing that unites the very distinct traditions of East and West, of the Old and New Worlds, of Greece and China and Mexico. Tall structures that stand for hundreds or thousands of years aren’t only expressions of race-spirit but also assertions of IQ. You have to be bright to build big. Architecture is also an example of the non-linear powers that high intelligence gives the groups that possess it. For example, European Whites or East Asian Chinese are not hundreds of times more intelligent than sub-Saharan Blacks or New Guinea tribesmen. Yet the structures created by the former races have been hundreds or thousands of times larger and taller and longer-lasting than the structures created by the latter. In a related way, the subversive and anti-Western Jewish billionaire George Soros is not thousands of times more intelligent than Kevin MacDonald or Steve Sailer or Vox Day. But he is, alas, thousands of times richer and more influential.

Unfettering intelligence from aesthetics

The subversive and anti-Western Jewish plutocrat Jay Pritzker was also thousands of times richer and more influential. And his influence, like that of George Soros, has been pernicious. As I pointed out above, Great Buildings describes the “prestigious Pritzker Prize” as “architecture’s highest honour.” But it’s an honor that goes to those who have smashed the millennial-long tradition of beauty and grandeur in architecture. When you reach the final section of Great Buildings, you enter an era of aesthetic atrocity and absorb the central lesson of modernism. The lesson is this: When intelligence is unfettered from aesthetics, you get atrocity. Modernism unfettered intelligence from aesthetics in architecture, whereupon the Western world was assailed with the architectural abortions of the twentieth century. You can see that radical and repulsive discontinuity in the single nation of France. Unlike beautiful Chartres Cathedral from the Middle Ages, which has elevated the spirit and enriched the life of France, the ugly Pompidou Centre has assaulted the spirit and undermined the life of France. Once again, it’s not a coincidence that Chartres was created by goyim and the Pompidou Centre by a Jew.

The Choir of Chartres Cathedral

The Choir of Chartres Cathedral

Chartres is also a reminder that Mencius Moldbug, aka Curtis Yarvin, was both utterly wrong and highly dishonest to give the name “The Cathedral” to the vast, interlocking system of anti-White and anti-Western activism, subversion, and propaganda that currently controls politics and the media. The beauty and grandeur of cathedrals like Chartres are integral to the West. But Yarvin’s so-called “Cathedral” hates cathedrals and the Christianity that inspired them. He should have of course have called that system “the Synagogue,” because Jews are central to its subversion and its hatred of the West. Why didn’t he give the hate an honest and accurate name? You won’t be surprised to learn that Yarvin himself is Jewish.

The Sydney Opera house (image from Infogalactic)

The Sydney Opera house (image from Infogalactic)

There are no synagogues in Great Buildings. And I don’t think Philip Wilkinson, the author of the book, is Jewish. He doesn’t have a Jewish name and most of his book is a celebration of genuinely great buildings that embody the beauty and grandeur of true architecture. Furthermore, two of the modern buildings he describes — the Chrysler Building in New York and the Sydney Opera House — aren’t architectural abortions. They don’t match the best of the past, but they too are great buildings. Perhaps they’re also glimpses of what the twentieth century’s architecture could have been like without the dominance of Jews.