“Cohen realised that it was not enough to describe the state as being made up of many political groups. Such a statement did not justify opening American borders to strangers or protecting strangers’ interests. Only a normative argument about the importance of diversity in individual and social life could give the outsider a place in American society.”

Dalia Mitchell, Architect of Justice: Felix S. Cohen and the Founding of American Legal Pluralism[1]

“Cohen’s life work revolved around what currently travels under the trendy buzzword diversity.”

Steve Russell, “Felix Cohen, Anti-Semitism, and American Indian Law.”[2]

Introduction

Contrary to Nathan Cofnas’s claim that modern multiculturalism can be attributed to the idea that “the West was on a liberal trajectory with or without Jews,” Jews have demonstrably been critical in the majority of significant legal developments in the advance of multiculturalism and cultural pluralism, both in Europe and in the United States. Brenton Sanderson has made an exceptionally strong case for the same to be said in relation to Australia. Absent detail of any kind, explaining the current ideological climate on race and immigration as the result of any kind of “trajectory” is really nothing more than a just-so story. It’s an untestable narrative explanation: “Things are the way they are, because that’s the way things were going.” To mention nothing from any period earlier than the twentieth century, this “liberal trajectory” has certainly been a highly anomalous one, featuring among other anti-liberal trends, the advent of radical conservatism, the rise of Fascism, the development of notions of a racial state, and the introduction of racially exclusionary immigration laws. That these laws were quite radically overturned in the United States, and in a very short span of time (1924–1965), would seem to represent a dramatic break from trajectory, rather than a natural flowing from one. What prompted this turn? Laws promoting multicultural understandings of citizenship were introduced from the 1960s, in the United States and elsewhere, which led to the gradual displacement of Whites in their own lands. One can prevaricate on how these destructive laws can be traced to the ideas of Rousseau, or any other Enlightenment philosophe, but it pays a greater scholarly dividend to focus instead on who exactly introduced these laws and what their immediate motivations may have been. These facts can be tested, often with reference to the unambiguous statements and explanations of the actors themselves. And these actors are often Jews.

One of the preoccupations in my writing for this website has been to issue warnings about changes in the law, particularly in relation to speech and censorship. I warned of the imminence of internet censorship, and the gross expansion of hate laws and the concept of terrorism, years before these things came finally to fruition. While I agree with most people that law is often downstream from culture, I find it undeniable that sometimes the two operate simultaneously and in tandem, with law driving and reinforcing cultural change, and sometimes preceding it entirely. Thus, whoever holds legal power influences culture, just as much as they who influence culture can manipulate the law. The group that holds both centers of power is powerful indeed.

The historical relationship of Jews with the legal apparatus of European and Western nations deserves close and special attention. There have been many successive legal as well as philosophical changes across the West over a number of centuries which have cumulatively resulted in the widening of the concept of citizenship, the end point of which has been the dominance of pluralistic understandings of citizenship in the bureaucratic state and the eventual permission of mass migration. The historical record is clear that in terms of these legal changes, Jews have been the dominant cause or instigators of modifications designed to introduce “tolerance” into the law, from the medieval charters establishing the tolerance of Jewish trading settlements in European cities[3] to Moshe Kantor’s contemporary “Secure Tolerance” project. This is to say nothing of overwhelming Jewish influence in the design and implementation of “hate laws” (see here and here) designed to uphold and strengthen the multicultural state.

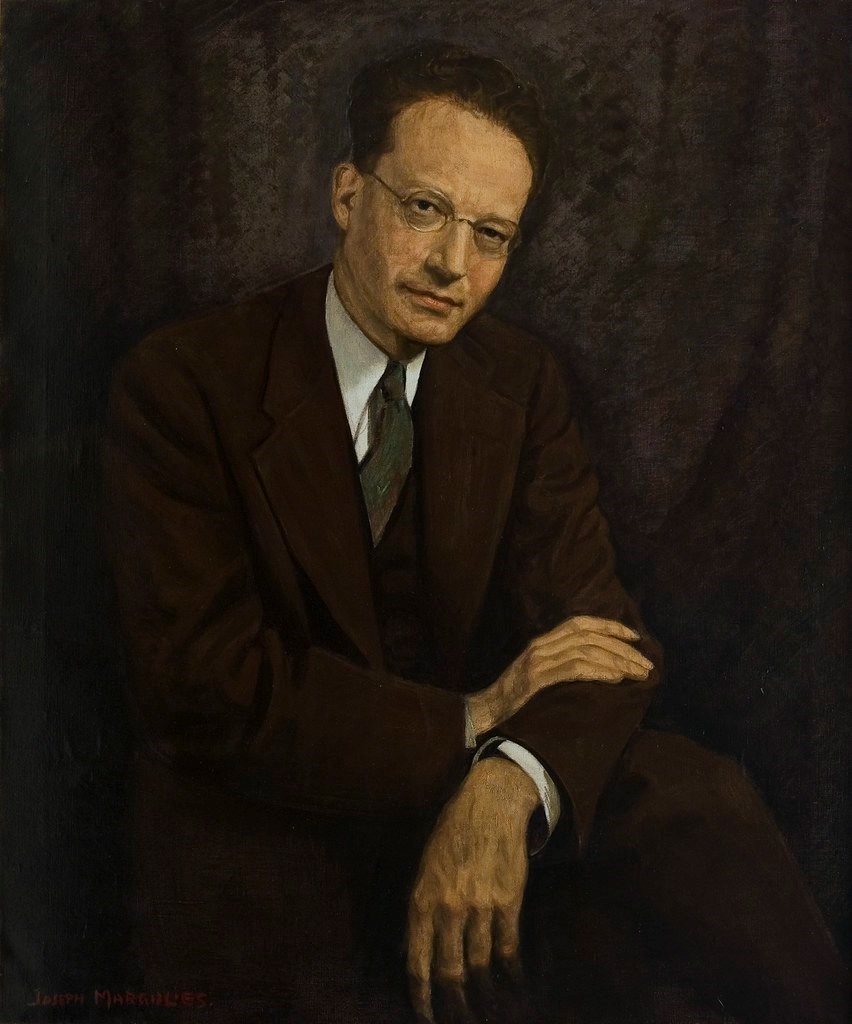

Kevin MacDonald has explored Jewish activism in the period of White ethnic defense from around 1890 through the 1924 and 1952 immigration laws, and the intense Jewish opposition to those laws. The role of Jewish activism was critical in enacting the 1965 law which revolutionized American immigration legislation and permanently changed America’s demographic destiny. In the following essay I want to build upon MacDonald’s specific illustration of Jewish legal influence in the expansion of pluralistic concepts of citizenship and culture in America by using the example of the Jewish philosopher and lawyer Felix Solomon Cohen (1907–1953). The career of Cohen offers something of a prequel to the 1965 activism, with Cohen emerging as a subtle but important forerunner of many of the ideas and approaches used to create present-day multicultural America.

Networks and Nepotism

For most readers, Felix Cohen will be an unfamiliar personality. This is hardly surprising when even the scholar behind his most substantial biography argues that “for the most part his work was behind the scenes.”[4] And yet Cohen was as stubbornly influential as he was elusive, with the same author stressing that his activism “had a profound influence on the transformation of law in the first half of the twentieth century,”[5] and that his story “is the story of the origins of multiculturalism.”[6] Cohen was born in Manhattan in 1907 and grew up in Yonkers. His father, Morris Raphael Cohen, was a philosopher at the City College of New York and a member of the New School for Social Research. Morris Cohen was extremely keen to promote “a new ideal, a cosmopolitan Jewish identity,”[7] and with it to expand Jewish involvement in American life.

Felix Cohen absorbed many of his father’s ideas, as well as grievances. Morris often complained that he had found it difficult to get a job teaching philosophy because of anti-Semitism[8], an explanation for personal failure that Felix would also eventually employ. Felix Cohen possessed a keen intelligence. He attended the City College of New York, where he rose in 1925 to become editor of The Campus. His early activism provoked such a storm of complaint, including one reader’s letter suggesting that “ungrateful kikes should get the hell out of here and go back to Trotsky’s paradise,” that he was dismissed by the magazine’s board. He left CCNY and later received an M.A. and Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University in 1927 and 1929, respectively. Cohen then entered Columbia Law School in 1928 and graduated in 1931. From his earliest days studying law, Cohen was destined to become a dedicated ethnic activist. Biographer Dalia Mitchell points out that Cohen’s generation of young Jewish lawyers “viewed the study of law as providing tool with which they could challenge the authority of the Anglo-Saxon elite in American life.”[9] For Cohen, this involved the “personal hope that American law could remedy wrongs against Jews, specifically forced exclusion.”[10] The primary weapon in this fight would be the promotion of pluralism within American law, both by expanding the concept of citizenship and weakening America’s borders.

Although beginning his career with a short stint at an average law firm, Cohen’s big break came thanks to FDR’s momentous decision to nominate Felix Frankfurter to the Supreme Court. Previously reluctant to hire Jews, the legal establishment in Washington was thereafter inundated thanks to a wave of ethnic nepotism ushered in by Frankfurter. Cohen biographer Alice Kehoe remarks that “Frankfurter unabashedly recommended young Jewish lawyers for federal positions to the point that newspapers wrote of the unprecedented number of Jews hired and of fears that a “Jewish cabal” was taking over America.”[11] Frankfurter was a close personal friend of Morris Cohen (the pair were also close friends with Horace Kallen), and when Frankfurter hired the family’s neighbour Nathan Margold to oversee the legal team at Department of the Interior, it was a foregone conclusion that Margold would in turn hire Felix Cohen to join the team. Like the Cohens, Nathan Margold, whose son would later become one of the first major porn barons in America, was an early activist for multiculturalism and author of the 1933 “Margold Report” which called for increased “civil rights” for Blacks.

Legal and Ethnic Warfare

Together at the Interior, Margold and Cohen initially decided to promote pluralism by focusing on the position of Indians/Native Americans in American law. The approach was thought particularly suitable because Cohen’s wife, Lucy Kramer, was an anthropologist working alongside Franz Boas (also a friend of Morris Cohen) at Columbia, where she focussed on promoting culturally relativistic understandings of Native American life. At one point, for example, Kramer wrote a manuscript titled Red Man’s Gifts to Modern America, which was so overblown and unrealistic that it was rejected by her editor with the comment: “Sounds too much as though ballyhooing. Something which she wants to believe.”[12]

Margold’s intention was to bring Cohen, whose ideology was shaped by his Jewish origins and “Franz Boas’s teaching of historical particularism and cultural relativism,”[13] into a leading position in Indian Affairs within the Interior, but the initial move to get Cohen appointed Associate Solicitor for Indian Affairs was complicated. Margold’s boss and Secretary of the Interior was the Anglo-Saxon Harold Ickes, who recorded in his private diary “I had decided not to appoint a Jew if I could avoid it.”[14] Ickes initially refused to hire Cohen, but made the mistake of explaining his reasons (suspicion of Jews) to someone else in the department. Legal historian Kevin Washburn comments “Ickes claims he was blackmailed into [hiring Cohen] when word got out that [anti-Semitism] was his reason.”[15] Cohen was thus appointed Associate Solicitor for Indian Affairs, and was set to work by Margold on a project that would transform the position of Indians/Native Americans in American law. One scholar has commented that, “though Cohen was still a young lawyer, he had highly sophisticated views of the law’s purpose and was working toward the development of a broader philosophy of cultural and legal pluralism. Indeed, his dissertation had addressed this theme, albeit in a broad theoretical manner.”[16] In one of the most prominent of Cohen’s legal changes in his new role, Indians/Native Americans automatically became United States citizens, whereas previously they could only become citizens via treaty.[17]

It’s interesting that Cohen’s Jewish biographers have been at pains to present Cohen as involving himself in the promotion of “Indian rights” for purely altruistic ends, whereas non-Jewish authors have been much more forthcoming in seeing Cohen as engaging in a kind of proxy legal war against White America and its racially exclusive approach to citizenship and immigration. University of Iowa’s Kevin Washburn has been particularly scathing of Jewish scholar Dalia Tsuk Mitchell’s glowing panegyric to Cohen, Architect of Justice: Felix S. Cohen and the Founding of American Legal Pluralism, and has asked:

Was Cohen’s interest in Indian law and Indian people purely platonic, intellectual, and ideological, as Mitchell implicitly suggests, or was it driven in part or wholly by a sense of shared experience with other oppressed peoples? … Did Cohen’s Jewish identity — and his feelings of being an outsider to the then-ruling elite in the United States — affect his views about Indian tribes?[18]

Washburn is skeptical about Cohen’s selfless altruism to say the least. He points out that Cohen once wrote “The Indian plays much the same role in our American society that the Jews played in Germany.”[19] And while Cohen was, in Mitchell’s phrasing merely “impatient” with Anglo-Saxon America’s “particularism,” he was strident in his insistence that Jews should be able to continue their separate existence within the ‘Melting Pot,” viewing Jewish assimilation as “cultural death,”[20] and telling one colleague that he would “punch … in the nose” anyone who suggested Jews “ought to be beneficially assimilated into the Anglo-Saxon Protestant mainstream of American life.”[21] In Washburn’s view, there was a clear ethnic struggle, and Mitchell’s biography “fails to cast light on the darker aspects of Cohen’s personal experiences as a Jewish-American civil servant in mid-twentieth century America.”[22]

Immigration and Open Borders

The activities of Cohen, Margold, and other Jews within the Department of the Interior, both in relation to the expansion of Indian “rights,” and issues of immigration and citizenship more generally, eventually escalated to the stage where they prompted a reaction from the Anglo-Saxon establishment. In early 1939 Cohen began agitating for immigration reform within Interior, eventually latching onto the idea of “developing Alaska” by settling large numbers of European Jews in the state (the Alaska Development Bill—Kehoe states that the entire bill was written by Cohen[23]). In his Harvard-published FDR and the Jews (2013), Richard Breitman writes that in 1939 “Interior Department official Felix Cohen presented a report indicating that industrious immigrants would boost the Alaskan economy and an expanded population would bolster the nation’s defense.”[24] In a move of crypsis eerily prefiguring attempts to use John F. Kennedy as the face of propaganda intended to pave the way for the 1965 immigration act, Margold and Cohen chose a non-Jewish department figure to act as figurehead for the bill. Breitman writes:

Undersecretary of the Interior Henry Slattery became its official sponsor, rather than Nathan Margold or Cohen, its senior proponents in Interior: for domestic consumption, the “Slattery Plan” sounded better politically than the “Cohen Plan.”[25]

While working on the bill, Cohen also published a lengthy article in the National Lawyer’s Guild Quarterly that essentially made the case for opening America’s borders to immigrants of all backgrounds. Titled “Exclusionary Immigration Laws: Their Social and Economic Consequences,” the essay was a full-frontal attack on Anglo-Saxon nativism. The article, which I have read in full, opens with a list of America’s exclusionary immigration laws, beginning with the 1882 act targeting Chinese migrants. Cohen remarks:

Each of the foregoing statutes was based in part on economic or materialistic grounds, and in part upon theories of racial or cultural superiority. … Tolerance develops as a way of life when people realize that strange faces, strange accents, and strange ideas do not necessarily portend disaster. … The greatest danger to American institutions comes from those who could cut off the living stream [immigration] that has been the source of our national life. … The effect of such a cutting off of immigration as is proposed by various bills now pending in Congress would be to make the entire country more and more like those regions which have been untouched by immigration in the past century. Our standard of living would be lower, our illiteracy rates higher, our prejudice against minority races, minority creeds, and foreigners generally would be more intense. … The human rights of the citizen are safe only when the rights of the foreigner are protected.[26]

Cohen’s article was later published as a pamphlet by the American Jewish Committee, and was essentially the “skeleton” text upon which most of the propaganda for the 1965 Act was based, including “John F. Kennedy’s” (really, an ADL/AJC project) Nation of Immigrants. Cohen was also behind the AJC’s most prominent pro-immigration material. In his Princeton-published Jews and Liberalism, for example, Marc Dollinger points out that the American Jewish Committee’s March 1949 landmark statement on “Americanizing our Immigration Laws” had been written in full by Cohen.[27]

Despite the obvious self-interest of Jews like Cohen and Margold in advocating for such radical changes in American law, the pair maintained the charade even under intense questioning in Congress. David Wyman, in Paper Walls: America and the Refugee Crisis, 1938–1941, writes that during the hearings “witnesses for the bill repeatedly maintained its major objective was development of Alaska and that its refugee features were only incidental.”[28] The two primary objectors to the bill were Robert R. Reynolds (Dem.) of North Carolina and Homer T. Bone (Dem.) of Washington. The pair questioned the given rationale behind the bill and “pressed these witnesses to agree that the legislation was really aimed mainly at helping [Jewish] refugees.” Reynolds was notable for denouncing the bill as “just a smoke screen” for Jews “to get in the back door.”

Cohen was, however, reluctant to give ground and maintained the charade, with Wyman reporting that Cohen “denied that the primary aim of the measure was to help refugees and stated that the immigration features were simply an essential means for carrying out the fundamental purpose of the bill, settlement of Alaska.” He fooled no-one, and the bill was crushed.

The activities of Cohen, Margold, and other Jews within Interior had by the 1940s raised considerable consternation among the Anglo-Saxon establishment. Both Cohen and Margold had developed an “Indian New Deal” that “emphasized the state’s obligation to protect the rights of minority groups” and “advocated constitutional protection for group rights.”[29] The response was rapid, taking Cohen and his clique entirely by surprise. In early 1940, Cohen was removed from the Indian project in front of his own staff by Assistant Attorney General Norman Littell, who explained that Cohen’s ongoing work on Indian affairs was found to have been of “inferior quality.”[30] A few months later, Cohen, now more or less aimless within the department, wrote to a friend that he had in fact fallen victim to an anti-Semitic “purge,” pointing out that all other individuals who had been fired alongside him were also Jewish (Abraham Glasser, Bernard Levinson, Theodore Spector, and Jacob Wasserman).[31] Cohen wrote that the firing was designed “to humiliate me personally before my staff and later to attack my scholarship and my character.”[32] Kevin Washburn suggests that Cohen may not have been wrong in assuming that he was targeted as a Jew, but adds that Cohen’s own activism played a role. In Washburn’s words, “Cohen may have been too pro-Indian” and as a cosmopolitan Jew attempting to chip away at Anglo-Saxon “particularism.” “Cohen was simply ill-matched to the task” of being a cooperative cog in the Interior’s machine.[33] Most interesting of all is the fact that Littell had earlier expressed the opinion that anti-Semitism had some basis in genuine conflicts of interest, and had once highlighted Jews as stronger economic competitors than Anglo-Saxons.[34] In other words, the purge may well have been the retribution of WASPs suddenly aware of what Frankfurter’s “Jewish cabal” was doing. In 1948, the increasingly sidelined Cohen left the department and never returned to government.

All of Cohen’s subsequent work is described by Mitchell as involving attempts “to make the American legal system more inclusive,” and until his death he retained “a personal sense of failure at his inability to build a pluralist [multicultural] state.”[35] Despite his individual failure, however, Mitchell insists that Cohen was extremely influential, and that his legacy was taken up by later activists. In Mitchell’s words, “even failed attempts to devise formalistic legal structures to accomplish pluralistic goals create peripheries where pluralism might flourish.”[36] In Cohen’s case, these peripheries were his introduction of Indian legislation and citizenship clauses that undermined the increasingly strong notion of the United States as a state designed to fulfil the destiny of Whites in a new continent. In this sense, Cohen’s activism and “peripheries” reached fulfilment in the 1965 Immigration Act, and in the multicultural America we see today.

Conclusion

Many of the events and tactics from Cohen’s career clearly anticipate later Jewish activism around the 1965 Immigration Act, as well as contemporary Jewish activism promoting immigration and multiculturalism. Of particular interest is the fact Jews like Cohen and Margold appear to have obtained their positions primarily through nepotism, and even blackmail, rather than merit. Interestingly, the possibility that threatening to expose one as an “anti-Semite” for not hiring a Jew could result in severe repercussions even during the 1930s shows that Jews had already made substantial progress in their ascent to elite status. MacDonald discusses this shift in his review of Joseph Bendersky’s The Jewish Threat: ‘Anti-Semitic Politics of the U.S. Army:

It is remarkable that people like Lothrop Stoddard and Charles Lindbergh wrote numerous articles for the popular media, including Collier’s, the Saturday Evening Post and Reader’s Digest between World War I and World War II (p. 23). In 1920–1921, the Saturday Evening Post ran a series of 19 articles on Eastern European immigration emphasizing Jewish unassimilability and the Jewish association with Bolshevism. At the time, the Post was the most widely read magazine in the U.S., with a weekly readership of 2,000,000.

The tide against the world view of the officers turned with the election of Roosevelt. ” Jews served prominently in his administration,” (p. 244) including Felix Frankfurter who had long been under scrutiny by MID [Military Intelligence Division] as a “dangerous Jewish radical” (p. 244). Jews had also won the intellectual debate: “Nazi racial ideology was under attack in the press as pseudo‑science and fanatical bigotry.” (p. 244) Jews also had a powerful position in the media, including ownership of several large, influential newspapers (New York Times, New York Post, Washington Post, Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Record and Pittsburgh Post‑Gazette), radio networks (CBS, the dominant radio network, and NBC, headed by David Sarnoff), and all of the major Hollywood movie studios (see MacDonald 1998/2001).

It is remarkable that the word ‘Nordic’ disappeared by the 1930s although the restrictionists still had racialist views of Jews and themselves (p. 245). By 1938 eugenics was “shunned in public discourse of the day.” (p. 250) Whereas such ideas were commonplace in the mainstream media in the 1920s, General George van Horn Moseley’s 1938 talk on eugenics and its implications for immigration policy caused a furor when it was reported in the newspapers. Moseley was charged with anti‑Semitism although he denied referring to Jews in his talk. The incident blew over, but “henceforth, the military determined to protect itself against charges of anti‑Semitism that might sully its reputation or cause it political problems. … The army projected itself as an institution that would tolerate neither racism nor anti-Semitism” (p. 252‑253).

Moseley himself continued to attack the New Deal, saying it was manipulated by “the alien element in our midst” (p. 253) — obviously a coded reference to Jews. This time he was severely reprimanded and the press wouldn’t let it die. By early 1939, Moseley, who had retired from the army, became explicitly anti-Jewish, asserting that Jews wanted the U.S. to enter the proposed war in Europe and that the war would be waged for Jewish hegemony. He accused Jews of controlling the media and having a deep influence on the government. In 1939, he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee on Jewish complicity in Communism and praised the Germans for dealing with the Jews properly (p. 256). But his testimony was beyond the pale by this time. As Bendersky notes, Moseley had only articulated the common Darwinian world view of the earlier generation, and he had asserted the common belief of an association of Jews with Communism. These views remained common in the army and elsewhere on the political right, but they were simply not stated publicly. And if they were, heads rolled and careers were ended.

The new climate can also be seen in the fact that Lothrop Stoddard stopped referring to Jews completely in his lectures to the Army War College in the late 1930s, but continued to advocate eugenics and was sympathetic to Nazism in the late 1930s because it took the race notion seriously. By 1940, the tables had turned. Anti-Jewish attitudes came to be seen as subversive by the government, and the FBI alerted military intelligence that Lothrop Stoddard should be investigated as a security risk in the event of war (p. 280).

Finally, it is also noteworthy that Cohen, Margold and their co-ethnics in government harbored a clear sense of ethnic grievance against Whites which was accompanied by entirely unconvincing denials of self-interest and flamboyant displays of superficial altruism in relation to other minority groups (Blacks for Margold; Indians for Cohen). Of primary importance to these activists was the need to boost the position of non-Whites within the American legal structure, either by manipulating what it meant to be a citizen (and what ‘rights’ and ‘obligations’ that entailed), or by expanding who could become a citizen. These legal manipulations and reversals, and their occurrence in the context of what amounts to a very clear and often explicit clash of ethnic interests between dedicated Jewish activist lawyers and the WASP establishment, raise serious questions about whether America was really on a “liberal trajectory” in which the current multicultural status quo was an inevitability.

[1] D. Mitchell, Architect of Justice: Felix S. Cohen and the Founding of American Legal Pluralism (Itchaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), 5.

[2] S. Russell, “Review Essay: Architect of Justice: Felix S. Cohen and the Founding of American Legal Pluralism,” Wacazo Sa Review, 23:2 (Fall 2008), 112-114 (113).

[3] J. Ray, “The Jew in the Text: What Christian Charters Tell Us About Medieval Jewish Society,” Medieval Encounters 16, 2-4 (2010): 243-267.

[4] Mitchell, 7.

[5] Ibid, 1.

[6] Ibid, 3.

[7] Ibid, 16.

[8] Ibid, 15.

[9] Ibid, 32.

[10] Ibid, 7.

[11] A. B. Kehoe, A Passion for the True and Just: Felix and Lucy Kramer Cohen and the Indian New Deal (Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 2014), 46.

[12] Kehoe, 86-7.

[13] Ibid, 5.

[14] K. K. Washburn, “Felix Cohen, anti-Semitism, and American Indian Law,” American Indian Law Review, 33:2, 583-605 (603).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid, 586.

[17] N. Pickus, Immigration and Citizenship in the 21st Century (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 1998), 55.

[18] Washburn, 600 & 603.

[19] Ibid, 604.

[20] Ibid, 587.

[21] Ibid, 604.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Kehoe, 5.

[24] R. Breitman, FDR and the Jews (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2013), 159.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Quotes taken from the reprint of the 1939 article which appeared in the Contemporary Jewish Record, 3:2, (March 1 1940), 141.

[27] M. Dollinger, Jews and Liberalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 268.

[28] D. Wyman, Paper Walls: America and the Refugee Crisis, 1938-1941 (Plunkett Lake Press, 2019).

[29] Mitchell, 5.

[30] Washburn, 601.

[31] Ibid, 599 & 601.

[32] Ibid, 601.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid, 602.

[35] Mitchell, 5 & 6.

[36] Ibid, 8.

https://www.