On a bright but cloudy morning on 9 August 1945, a B-29 bomber, named “Bocks Car”, of the US Army Air Force, flew over the Japanese port city of Nagasaki and dropped a highly radioactive Plutonium implosion bomb onto the city, 300 yards from the second largest Roman Catholic cathedral in the Far East, Urakami Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The bombing was personally ordered by US President and Democrat Party leader, Harry Truman.

The story is now partly the subject of a major new film named after the US scientist who led the Atom bomb programme – called the Manhattan Project – namely Dr J Robert Oppenheimer.

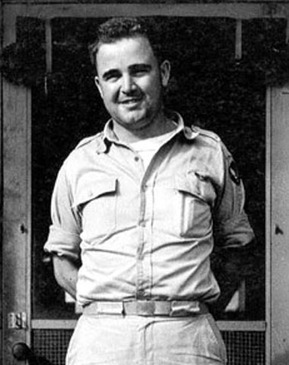

It is said that the pilot of Bocks Car, Major Charles Sweeney, an Irish-American, brought up Roman Catholic, had not had a clear view of the initial target, Kokura (now Kitakyushu), and, running out of fuel, headed back over Nagasaki when he spotted the turret of the Cathedral. Concluding that must mean there were people nearby it, he decided to drop the bomb more or less on top of it.[1]

Whether he knew it was a Roman Catholic Cathedral or not is unclear. What is clear is that, ever after, and long after he learned that Urukami Cathedral was Catholic, Sweeney continued to claim that dropping the bomb was necessary and good.

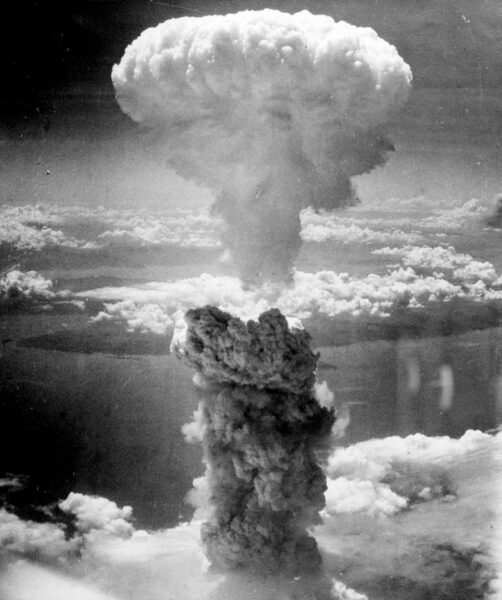

The bomb exploded at 11:02 in the morning and blew most of the Cathedral, most of the city, and most of its inhabitants to smithereens in a blinding flash.

The remains of the city were engulfed in a massive emission, and the consequent dust cloud of toxic radiation caused large numbers of the few that survived the blast to die over the next days, months and even years – some even 20 years later – from acute radiation poisoning.

Bocks Car had dropped what is known in the nuclear trade as a “dirty” bomb, meaning that, upon exploding, it would release a very high emission of poisonous nuclear radiation.

This was the nuclear bomb that went on giving for years after it was dropped – giving to the people of Nagasaki the horrible after-effects of nuclear radiation that slowly kill victims for years.

The vast majority of the people obliterated and vaporised by this fearsome weapon were civilians, children, women, elderly – almost all of whom had nothing to do with the war save to endure the constant air attacks of Allied bombers and the loss of their husbands, fathers, brothers and sons in the conflict. Children were blasted to tiny pieces of mangled flesh and fractured bone by a huge bomb dropped right on top of them.

The US Target Committee, chaired by Brigadier-General Leslie Groves on the appointment of General George C Marshall, then Chief of Staff of the US Army, consisted partly of military officers, and partly of scientists from the Manhattan Project.

They were deeply unqualified to choose targets in Japan for any kind of bomb, let alone an atomic bomb. However, Kyoto was originally on the target list but was taken off by order of US Secretary of State, Henry L Stimson.

According to Edwin Reischauer, a US Army Intelligence officer and Japanologist, “the only person deserving credit for saving Kyoto from destruction is Henry L Stimson, the Secretary of War at the time, who had known and admired Kyoto ever since his honeymoon there several decades earlier.” Stimson had discovered that the historic city of Kyoto was one of the great artistic centres of the world.

But this came about by pure chance. The Target Committee was otherwise unequipped to understand such issues and focussed only on city size and population numbers.

Very little research was needed to discover that the city of Nagasaki was the one city of Japan that was most likely to be friendly to the Western Allies, not only because it was a port city where, even when Japan was closed and isolated, foreigners would still enter and visit, but also because of a vitally important cultural reason.

That vital reason was that the city of Nagasaki was the very epicentre of Japanese Catholicism.

It had become so after the arrival of European missionaries, like St Francis Xavier, in the 16th century. They found the Japanese receptive to Christianity and declared that the Japanese were a naturally religious people. Even famous Samurai (feudal knights) and Daimyo (feudal lords) began to convert to Christianity. So many people converted that the government took fright and began to persecute Christianity in order to stop its spread.

Not only was Nagasaki the centre of Japanese Christianity, but it was the city in which Japanese Catholic martyrs, St Paul Miki (Feast Day 6 February) and his companions, in 1597, had been put to death by crucifixion and piercing by spears during the widespread persecution of Christians under the Tokugawa Shogunate of Tokugawa Ieyasu, Emperor Ogimachi and imperial regent, Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

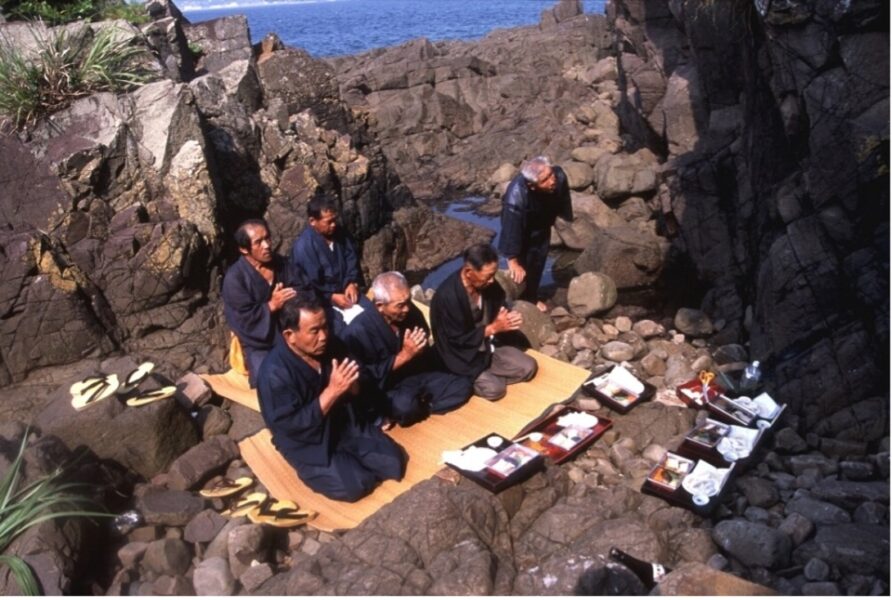

Thereafter, the Christians of Nagasaki were compelled to hide their religious beliefs during a long period of persecution that accompanied the seclusion policy of the Japanese government cutting Japan off from the rest of the world for some 250 years.

These underground Christians were later to be known as Kakure Kirishitan (“hidden Christians”) i.e. Japanese Catholics who went underground at the start of the Edo period in the early 17th century due to persecution.

From the beginning of the isolation of Japan until the re-opening of Japan in the 19th century, these Kakure Kirishitan kept the Catholic faith, cunningly disguising it under a veneer of apparent Buddhism, without a single Catholic priest to provide them with the Sacraments or to catechise their children.

They kept the Faith secretly, making their priestless Masses and services appear like Buddhist services and their statues of the Virgin Mary and the saints appear like Buddhist statues so as to avoid persecution by the authorities.

The authorities, whenever they uncovered a secret Christian, would force them to stamp or spit upon the Cross, or upon an image of the Virgin Mary, on pain of death to those who refused. This resulted in many more Japanese Christian martyrs who, after refusing to desecrate Christian symbols, were then executed, often by crucifixion.

When, in 1863, two French priests from the Société des Missions Étrangères, Father Louis Furet and Father Bernard Petitjean, landed in Nagasaki with the intention of building a church honouring the principal martyrs of Japan, they were astonished to discover tens of thousands of Kakure Kirishitan living in Nagasaki, a large number living in Urukami village (the district of Nagasaki where the Cathedral was later built).

A church was finished in 1864 and later became Oura Cathedral dedicated to the Japanese martyrs. Before long, tens of thousands of underground Christians came out of hiding to attend the Masses and services being held in the newly built church in Oura.

Approximately 30,000 secret Christians came out of hiding when religious freedom was re-established in 1873 after the Meiji Restoration. These Kakure Kirishitan were also known as Mukashi Kirishitan (“ancient Christians”).

When news of this reached Blessed Pope Pius IX in Rome, he declared it “the miracle of the Orient.”

Construction of Urakami Cathedral began in 1895, after the long-standing ban on Christianity was lifted.

The missionary clergy purchased, from a village chief, land where the humiliating interrogations of hidden Christians had taken place for two centuries.

When completed in 1925, it was the largest Christian structure in the Asia-Pacific region until the construction of the still larger Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Hong Kong.

It became the Co-Cathedral of Nagasaki together with Oura Cathedral.

Both cathedrals were blown to bits when Bocks Car dropped its deadly pay-load on the unsuspecting capital of Japanese Christianity, the one part of Japan that could reasonably be expected to be most favourable to the Western Allies. Nolan notes these numbers:

Of the approximately 12,000 Christians living in Urakami at the time, 8,500 were killed, including several dozen parishioners and two Catholic priests, who were hearing confessions in the cathedral that morning.

James Nolan, Atomic Doctors: Conscience and Complicity at the Dawn of the Nuclear Age (Harvard University Press, 2020), 115.

As the late and world-famous Catholic philosopher at Oxford University, Professor Elizabeth Anscombe, wrote the following when protesting in 1956 at her College giving Truman an honorary degree:

…bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The decision to use them against people was Mr Truman’s. For men to choose to kill the innocent as a means to their ends is always murder, and murder is one of the worst of human actions… In the bombing of these cities, it was certainly decided to kill the innocent as a means to an end. And a very large number of them, all at once, without warning, without the interstices of escape or the chance to take shelter, which existed even in the ‘area bombings’ of the German cities.[2]

By no standard of morality known to man could this horrific war crime ever be justified. The deliberate decision to bomb to smithereens non-combatant children, women and elderly people is always and everywhere a shameful form of mass murder every bit as immoral as mass-murdering Jews and other non-combatant minorities in concentration camps.

Those children, women and elderly had nothing to do with the declaration and prosecution of the war, which was, from the beginning, a decision only of their government and not them. Therefore, deliberately to target these non-combatants was, and is, an obviously immoral war crime.

But to choose Nagasaki as a target for the dropping of an atomic bomb was an act, not only of grave criminality and immorality, but of intense stupidity and strategic folly.

But how many people know the real story of the decision to drop an Atom bomb onto the centre of Japanese Catholicism? Very few, in my experience.

As with the equally immoral bombings of civilians in Germany, the numbers killed are grossly under-stated by Western leaders and historians, chiefly, one suspects, out of an attempt to minimise the shame of what they must know were gravely immoral acts.

The late UK Labour Party member of the British House of Lords, Lord Snow, himself an accomplished scientist and civil servant, set out in the Godkin lectures of 1960, later collected into a book entitled Science and Government, in precise detail, the sorry story of the near-complete failure of the Allied carpet-bombing campaign against Germany during World War II, reaching its peak in 1944.

He cites Nobel prizeman, Professor Patrick, Lord Blackett OM, CH, FRS, another member of the British House of Lords and scientific adviser to the British Admiralty during the War, as saying that the carpet-bombing campaign, by attacking civilian rather than military targets, lengthened the war by at least 6, if not 12, months, a persuasive indictment against the strategic bombing campaign.

Lord Snow cites both Lord Blackett and the official naval historian of the War, Captain Stephen Roskill CBE, DSC, FBA, RN (brother of the British judge and member of the UK’s then highest court, the Judicial Committee of the House of Lords, Lord Roskill), as agreeing that the diverting of long-range bombers to bombing German cities instead of protecting the Atlantic convoys very nearly cost the Allies the Battle of the Atlantic and thus the whole war, so foolish a policy was it.

The final proof, if more were needed, was later provided by the post-war survey of the bombing results, entitled The Strategic Air Offensive Against Germany 1939-45 compiled by historian Dr Noble Frankland CB, CBE, DFC, and diplomat and historian, Sir Charles Webster KCMG, FBA.

This survey showed that the calculated results of bombing civilian areas were grossly over-estimated, not only by partisan, pro-carpet-bombing advocates, like Churchill’s primary scientific adviser, Professor “the Prof” F A Lindemann, Lord Cherwell, but even by opponents of carpet bombing within the Civil Service, including scientists and permanent civil service department heads like Sir Henry Tizard GCB, AFC, FRS.

Even more embarrassing were the less-than-wholly-approving conclusions of the US Strategic Bombing Survey, commissioned by Secretary Stimson.

In fact, the US survey concluded, in relation to the atomic bombings, that “based on a detailed investigation of all the facts, and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey’s opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.”[3]

And yet we are repeatedly and persistently told, by apologists for the atomic bombing, that the war would not have ended if the atomic bombs had not been dropped and that they were thus a moral necessity.

This view simply does not accord with the known facts.

In fact, the Imperial Japanese government had already made peace overtures, via the Soviet Union.

Professor Elizabeth Anscombe makes reference to them in her 1956 pamphlet when she writes:

In 1945, at the Potsdam Conference in July, Stalin informed the American and British statesmen that he had received two requests from the Japanese to act as a mediator with a view to ending the war. He had refused.[4]

Stalin, anxious to waste the energies, men and resources of both the Allies and the Japanese, simply refused the peace offers, hoping that the Allies would think the Japanese were being insanely obstinate and that only an invasion of the Japanese mainland would bring them to their senses.

The first experimental atomic bomb was exploded in the desert at Almogordo, New Mexico, on 16 July 1945, just in time for the Potsdam Conference which began the very next day.

On the same day, Dr Leo Szilard and 60 other scientists protested the use, without warning, of the atomic bomb in Japan, emphasizing the moral responsibility for such use of weapons of mass destruction.

Although the US government ignored such protests, the Japanese government, on the very next day, 18 July 1945, submitted one of its requests for peace arbitration to the Soviet Union.

Thus, long before the atomic bombs were dropped, the Japanese were already suing for peace.

However, the pilots and their leaders were now already well hardened to the consequences of carpet bombing since they had long been carpet bombing Tokyo and other Japanese cities, just as their colleagues had done to German cities.

The damage suffered by these cities was even more extensive than that caused by the atomic bombs.

In all the carpet-bombings, almost all of those killed were innocent, non-combatant civilians, mostly children, women and the elderly.

I recently visited Japan with the Burma Campaign Society on a goodwill and reconciliation tour to bring together some of the few remaining survivors of the war.

We were very happy to see 97-year-old former Fusilier, Richard Day, shaking hands with former Japanese infantry sergeant-major, 104-year-old Katsuo Sato, as both had been enemy belligerents at Kohima during the war in Burma. They now greeted each other as reconciled friends.

Our Japanese hosts could not have been more hospitable, friendly, and courteous. It was a pleasure to meet and spend time with them.

At the various press conferences held, I made clear, as a former serving British officer, my moral objections to the Allied atomic and carpet bombing of innocent Japanese non-combatant civilians during that war, particularly Nagasaki, the centre of Japanese Christianity. This became a point of particular interest for the Japanese reporters, and I was questioned about it.

We visited Nagasaki, seeing both the hypocentre of the explosion and the peace park.

A part of Urakami Catholic Cathedral has been erected at the hypocentre to remind all that the bomb was dropped only 300 yards away from that cathedral, which had only been finished 20 years earlier, in 1925.

By an extraordinary coincidence, we met an elderly lady, aged 97, accompanied by her daughter and granddaughters, coming out of a restaurant, who had witnessed, not only one, but both atomic bombs.

Having just seen the bomb at Hiroshima, she escaped to Nagasaki expecting to be safe only to see the second bomb. She was fortunate – she survived both.

But curiously, in this city, once the centre of Japanese Christianity, not a single religious symbol has been allowed to be erected at any of the sites dedicated to the memory of the bombing. Despite repeated enquiry, I was not able to find any proper explanation of it.

My tentative conclusion was that, to avoid any contention about which religious symbols would be appropriate in a city where the Kakure Kirishitan had been persecuted by their Buddhist and Shinto brothers, the authorities must have decided that all religious symbols were to be excluded.

However, as always happens when religious symbols are excluded, this simply meant, and still means, an entirely self-contradictory victory for Atheism and secularism, the very reverse of what should be commemorated at such a tragic site.

Thus, as I mounted the escalators to go up to the peace park, what were the first two memorials that I encountered after entering?

One from the Soviet Union and the other from the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic!

Christianity could not be celebrated at the site of this, the most Catholic part of Japan, destroyed by a cruel and brutal atomic bomb, but Communism, a totalitarian ideology of the Soviet Union that had refused the Japanese peace requests which might otherwise have prevented the bombing, was allowed to erect its false and mendacious monuments.

I call upon President Putin of Russia and President Pavel of Czechoslovakia to insist that the Nagasaki city council pull down these deceitful monuments and replace them with Christian monuments from Russia and Czechia to commemorate the fact that the bomb was dropped upon the centre of Japanese Christianity.

And I call upon the governments of the free world, and the United Nations, likewise, to acknowledge the criminal nature of that bombing and to pledge never again to allow such wholesale mass destruction of innocent, non-combatant children, women and elderly people, to take place.

But is this a lesson that mankind is willing to learn or even acknowledge?

There are rules and laws of war designed to protect the innocent, but will belligerent nations respect them?

As war rages in Ukraine and in the Middle East, these questions are as relevant today as they were in 1945. Our failure to admit the crimes that have been committed by our own side will not help resolve the issues but, on the contrary, will only serve to worsen them.

War criminals and terrorists must learn that the truth will come out eventually and that the laws of war are there to be obeyed, not flouted.

And the simple rules of morality in war do not change merely because of the growth of technology.

It is always wrong to target innocent non-combatants, it always has been, and it always will be. The sooner governments remind themselves of this basic principle, the better.

The Feast Day of St Paul Miki, Japanese Christian martyr, is 6 February.

[1] This story was told to me by Ambassador Koji Tsuruoka, the former Japanese Ambassador to Britain who is himself a Catholic. There is some dispute about this claim, but in any case we know that the bomb detonated very close to the cathedral.

[2] Anscombe, Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret (1956). Mr Truman’s Degree. Oxford: Oxonian Press.

[3] The United States Bombing Surveys (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University Press. 1987. p. 107. Truman Library: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, July 1, 1946. Truman Papers, President’s Secretary’s File. Atomic Bomb.

[4] Anscombe, op. cit.