Why did college graduation rates increase while

college students became academically less prepared? A new study concludes it’s

probably because colleges have lowered their standards.

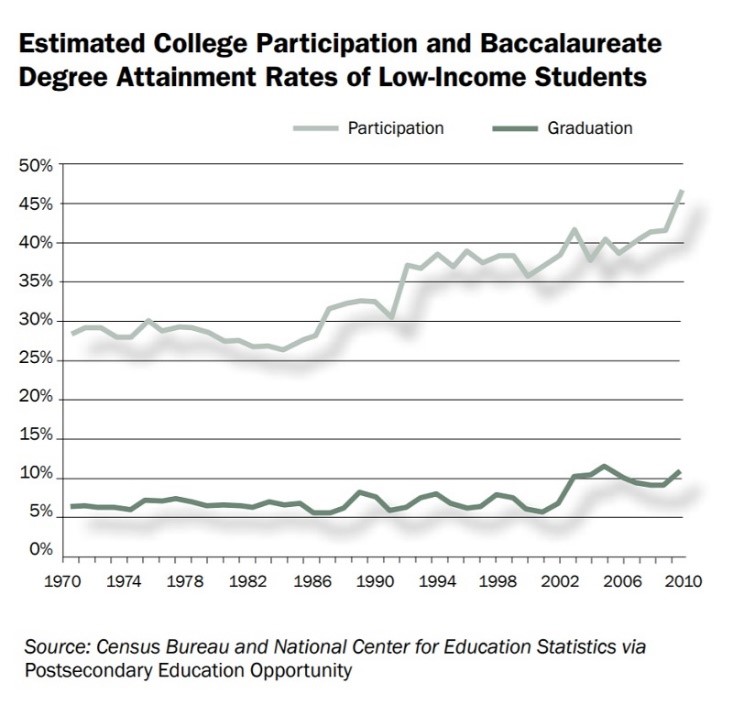

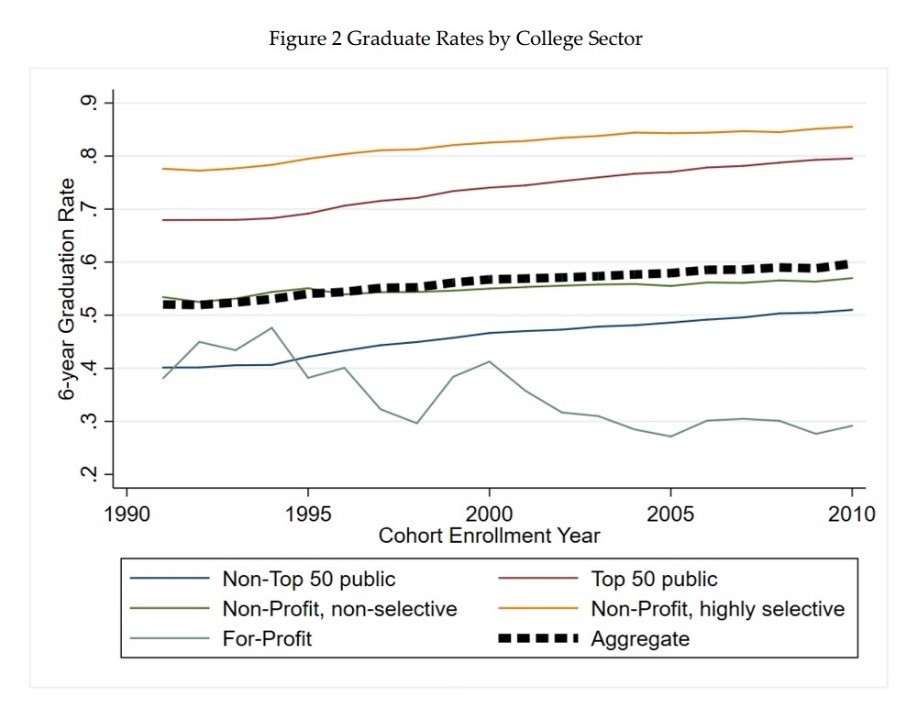

In the

1990s, only 40 percent of students who entered a four-year state college

graduated within the next six years. In the 2000s, that six-year graduation

rate increased—to 50 percent. But during that timeframe more poorly prepared

students also entered college, so one would expect a drop in

graduation rates, not the opposite.

So why did

the opposite happen? A new study from Brown University, reported recently in The

Atlantic, examines that question and concludes the most likely

reason is that colleges have lowered their standards even further.

While

student achievement over this timeframe decreased, as measured by math test

scores, their college grade point averages and graduation rates increased. In

other words, it appears colleges are further inflating these measures, a trend that

has been documented since federal taxpayer funding of so-called higher

education exploded.

“Our

findings combined with trends in studying and labor force participation in

college suggest standards for degree receipt have changed,” the researchers conclude.

They controlled for students’ background characteristics like family income and

race, the majors they choose, and the kind of colleges they attended, and found

all of these “explain little of the change in graduation rates.”

“Put another way, equally prepared students with the same family

income, parental education, gender, and institution type have higher GPAs” in

2004 than they did in 1998 and are more likely to graduate, write study authors

Jeffrey Denning, Eric Eide, and Merrill Warnick. Other studies have found that

a similar dynamic has been at work in U.S. high schools for at least a century.

Graduate the Kids Or

Else

It is probably no coincidence that this trend happened as state

and federal governments started measuring colleges by graduation rates because

more enrollees drop out of public institutions than graduate. One factor that

supports this conclusion is that the study documented bigger increases in

graduation rates and GPAs among public institutions despite their

lower-performing student bodies compared to private institutions.

While

between 2000 and 2015 federal taxpayers spent $300 billion on Pell Grants, the

most spendthrift federal college program, a 2014 federal review found

that 61 percent of recipients did not earn a

bachelor’s degree within six years of starting college. Once a program for

lower-income students, Pell Grants now fund the majority of college students,

and many are from middle-income families. The program spent $26.9 billion in

2016-17, the most recent academic year for which data is available.

Pell

recipients’ graduation rates are markedly lower than those of non-recipients, a

2015 Hechinger Report analysis found.

That’s not surprising, because students do not have to earn Pell subsidies

through academic achievement.

The sparse data available shows

the typical Pell recipient has a lower SAT score than the average test-taker

(914 versus 1010). In other words, the typical Pell recipient is the higher

education equivalent of a subprime mortgage. And now Democratic presidential

candidates want taxpayers to bail out yet another system politicians have

inflated to dangerous levels, by expanding this setup through various

incarnations of “college for all.”

Lots of Accountability

Talk, Zero Action for Decades

The federal

government has a history of not

publishing graduation rates and other important data for Pell Grants,

notwithstanding neverending bluffing from U.S. education secretaries from both

major parties about “accountability.” Lawmakers have not yet applied the most

effective consequence to low-performing students and institutions: yanking

taxpayer funds. Government “accountability” measures usually involve more

bureaucrats filing more reports, thus siphoning even more resources away from

students.

This has helped college waste four to six more years of many American

young people’s lives, rather than channeling their energy into productive,

entry-level jobs, which can more quickly and effectively develop their skills.

The

wastefulness of most so-called higher education has also been documented for

decades. “Full-time” college students report that on average they spend less than 20 hours

per week on academics. They spend almost three times as much of

their days on shopping, eating, socializing, and other leisure activities as on

academics. College students today spend less than half the time on

academics than students did several decades ago.

This is

partially because college has gotten easier. Economist Bryan Caplan notes in

another Atlantic article the poor mental abilities the average college graduate

demonstrated 16 years ago:

In 2003, the United States Department of

Education gave about 18,000 Americans the National Assessment of Adult

Literacy. The ignorance it revealed is mind-numbing. Fewer than a third of college graduates received

a composite score of ‘proficient’—and about a fifth were at the ‘basic’ or

‘below basic’ level. You could blame the difficulty of the questions—until you

read them. Plenty of college graduates couldn’t make sense of a table

explaining how an employee’s annual health-insurance costs varied with income

and family size, or summarize the work-experience requirements in a job ad, or

even use a newspaper schedule to find when a television program ended.

[emphasis added]

In 2011,

Richard Arum, Josipa Roksa, and Esther Cho found that 45 percent of college

students make no measurable learning

advances in their first two years of college. Thirty-six

percent made no improvement in all four years of college. “In an extensive

review of the literature presented in How College Affects Students,” they

noted, “Ernest Pascarella and Patrick Terenzini estimated that students in the

1980s learned at twice the current rate.”

Things have

only gotten worse since these studies and their underlying data were compiled

and analyzed, one reason such information is only rarely compiled. In the Common Core era,

which began in 2010, K-12 student achievement has been at best stagnant, and in

several cases apparently declining. Thus while students are getting

less-prepared for college, more are getting higher grades and graduating.

Are Colleges Juking

Stats Under Government Pressure?

Outside of top-tier institutions, both public and private,

six-year graduation rates remain shockingly low, even with the recent increase.

Plenty of research shows that graduating is what confers the vast majority of

the wage jump for those who attend college.

That plays into a phenomenon called “signaling,” an economic term

that means the typical college degree says less about whether someone actually

learned anything in college than the kind of person he or she probably was

regardless of attending—reasonably punctual, able to endure boredom, possessing

a better work ethic than those who don’t graduate college.

“As a society, we continue to push ever larger numbers of students

into ever higher levels of education. The main effect is not better jobs or

greater skill levels, but a credentialist arms race,” Caplan says, based on the

relevant economic research.

In other words, we are forcing students to spend tens of thousands

of dollars and four to six years of their prime checking meaningless boxes just

to make hiring easier for employers and to preserve the jobs of the people

babysitting them in the meantime. Oh, and to confer on everyone involved a

probably outsized view of their intellectual achievements and social worth.

Are the Economic

Benefits of a Degree Declining?

But as

gradually greater percentages of high school graduates attend college—67 percent of

the high school class of 2017 enrolled in college that fall—this signaling

feature of a college degree seems to have declined. So also may be the higher

salary college graduates earn on average compared to those who didn’t graduate

college.

Several

recent studies have found that the lifetime economic benefits of a college

degree have flatlined or are even declining. A 2019 study found

that for Americans born after 1977 the college wage premium has declined on

longitudinal measures (although it only flatlined on non-longitudinal surveys,

instead of declining).

“A primary implication of our findings is that the demand for

skill is flattening and may even be falling… This interpretation is consistent

with recent literature cited above that has documented declining income and

employment prospects for younger birth cohorts,” write study authors Jared

Ashworth and Tyler Ransom. This suggests that as the pressure to attend college

has increased, the actual value that students derive from doing so has

flattened or declined.

The economic

value of a generic college degree has long been in question. College pushers

like to note that people who get degrees earn higher lifetime incomes. But that

doesn’t prove those higher lifetime incomes represent real value rather than

the result of social stigmas and economic discrimination, such as in requiring

applicants to have a degree for jobs that don’t actually need one, which is

endemic. Caplan’s 2018 bookamasses

loads of economic research to make this case.

As

economist Richard Vedder noted in 2012,

after “[c]ontrolling for other factors important in growth determination,

the relationship between education spending and economic growth is negative or,

at best, non-existent.” In other words, there’s plenty of good evidence to

suggest that, for many or even most of today’s enrollees, college is a

taxpayer-backed scam.

A Subprime College

Bubble

Just like easy federal money and identity politics-driven mandates

pushing home buying that led to the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, easy money

for college has especially lured poor and poorly prepared students into

colleges from which they won’t graduate but will accumulate crippling debt.

“[I]t

appears that the Pell Grant Program has led more low-income high school

graduates to enter college,” write Jenna Robinson and Duke Cheston in a 2012 Pope Center paper.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER),

a private research organization, recently reviewed and published a study on the

available literature on financial aid. It concluded that lowering the annual

price of higher education by $1,000 (either through tuition reductions or

non-repayable aid) leads to a 3 to 5 percentage point increase in postsecondary

attendance.20 In other words, the effect of $100,000 spent on one hundred

students would be that three to five students who would not have chosen to go

to college would change their minds because of the availability of increased

aid.

It’s an injustice. This easy money system exploits the poor and

disadvantaged to make better-off people comfortable. Those who profit from this

mess include businesses that don’t have to train employees, college staff whose

jobs remain secure, spenders and lenders taxpayers are pressured to bail out,

and voters who refuse to demand an end to a taxpayer-funded system that fails

at least half the people who enroll in it, so long as their kids can get other

people to pay for their degree.

But unchecked corruption only grows. This endemic corruption of

U.S. education is now affecting everyone involved, rich and poor alike, a

probable majority of whom are being cheated out of a real education and a real

start in life. Inflated GPA numbers can only hide that reality for so long

before America’s education bubble finally pops.

Joy Pullmann

(@JoyPullmann) is

executive editor of The Federalist, mother of five children, and author of

"The Education Invasion: How

Common Core Fights Parents for Control of American Kids." She

identifies as native American and gender natural. Her latest ebook is a list of more than 200

recommended classic books for children ages 3-7 and their parents.

Photo U.S. Air Force

photo/Karina Brady