“Five

Jews came from over sea with gifts to Tairdelbach [King of Munster], and they

were sent back again over sea.”

Annals of Inisfallen, 1079 A.D.

Annals of Inisfallen, 1079 A.D.

“I

propose an interrogation of how the Irish nation can become other than white

(Christian and settled), by privileging the voices of the racialised, and

subverting state immigration, but also integration, policies.”

Ronit Lentin (Israeli academic), From racial state to racist state: Ireland on the eve of the citizenship referendum, 2007.

Ronit Lentin (Israeli academic), From racial state to racist state: Ireland on the eve of the citizenship referendum, 2007.

Prelude

Tairdelbach

of Munster (Turlough O’Brien 1009–86), who was, by 1079, effectively the High

King of Ireland, probably holds the world record for the fastest expulsion of

Jews. He dominated the Irish political scene, had crushed the Viking leadership

of Dublin, and possessed “the standard of the King of the Saxons.” His son had

even commenced raids into Wales and the British coast. Unfortunately, we can

only surmise the nuances of the 70-year-old warlord’s reaction to the sudden

arrival of a handful of gift-bearing Jews, because the Annals of Inisfallen are

thin on detail. The delegation almost certainly originated in Normandy, where

Jews thrived under a symbiotic financial relationship with William the

Conqueror. William, of course, had introduced Jews to Anglo-Saxon England

thirteen years before the approach to Tairdelbach, leaving open the possibility

they could have travelled directly to Ireland from one of these new Jewish

enclaves in England. In any event, it is almost certain that they arrived

seeking permission to settle in Ireland’s urban centers, forge a relationship

with the Irish elite (Tairdelbach himself), and engage in exploitative

moneylending among the lower social orders. This was a pattern that had

hitherto been witnessed throughout Europe. And yet Tairdelbach’s reaction was

to reject the gifts and immediately expel the Jews. They would not be able to

form a community in Ireland for several centuries.

It’s

probably no coincidence that Tairdelbach was regarded in his lifetime as a good

and Christian king. He enjoyed close relationships with the Irish church, and

the church in England, and was patron to a number of religious figures and

scholars. He was almost certainly a literate and educated man, and his decision

to expel the Jewish delegation may have been based on a body of knowledge

rather than mere instinct. Historians Aidan Beatty and Dan O’Brien comment on

the expulsion:

No

one in Ireland had ever seen a Jewish person prior to this incident, yet the

visitors are unambiguously described as “five Jews” (coicer Iudaide) and the Irish people already

have a word for Jews, Iudaide, a medieval Gaelic word that clearly has its roots in the

languages of classical antiquity. But more than that paradox, there is also a

certain kind of cultural knowledge at work here. The medieval Irish who gave

such short shrift to these Jewish guests “know” something about Jews, or more

accurately they think some things about Jews: they “know” that Jews are not

trustworthy, that Jews bearing gifts are not to be taken into one’s care. And

Jews are not suitable for residence in Ireland – they should be expelled from

the country.[1]

The

impression is therefore that Tairdelbach was a savvy and selfless leader, who

sought the good of his people more than the good of his own short-term financial

situation.

Jewish

revenge, direct or indirect, occurred a century later, when the glory days of

the Gaelic High Kings like Tairdelbach came to an end thanks to the Norman

invasion of Ireland by Richard “Strongbow” de Clare. In common with the Norman invasion

of England, Strongbow was financed by Jews, in this case an England-based

Jewish financier named Josce of Gloucester. After the Norman invasion, the new

Norman elite brought a small number of their Jews into Ireland, primarily for

financial activities at ports rather than large-scale settlement. A grant dated

28 July 1232 by King Henry III to Peter de Rivel gave him the office of

Treasurer and Chancellor of the Irish Exchequer, the king’s ports and coast,

and also “the custody of the King’s Judaism in Ireland.” These few nameless

Jews would have been dispensed with after the expulsion from England in 1290,

and Jews were absent from Ireland until the time of Cromwell, who also holds a

special place of notoriety in Irish history.

By

following in the wake of the Normans and the English, the Jews have certainly

placed themselves on a dubious historical trajectory in relation to the Irish.

But perhaps nothing seen in the past compares with what is seen in the present.

Because it is globalism that has now invaded Ireland, and Jewish activists are

shaping the thought and policies of the new global-imperial culture.

Mass

Migration and Indoctrination

Between

2002 and 2016, the proportion

of the Irish population born abroad rose from 5.8% to more than 17%.[2] Given

the relatively small population of Ireland, if the current pace of immigration

persists, the Irish stand to be overwhelmed in their ancient homeland in the coming

decades. The biggest increases have come in the form of growing numbers of

Pakistanis, Romanian gypsies, Afghans (an increase of 212% on the previous

census), and Syrians (an increase of 199% on the previous census). Ireland has

also become home to a large and rapidly growing African population, which has

been described by

University College Dublin academic Philip O’Connell as being mired in

“exceptionally high unemployment rates.” The African population has also

presented some novel difficulties for the Irish police who have had to bust

a West African fraud ring in

Dublin and Meath, contend with Black gangs attacking each other with

machetes in the middle of busy roads, deal with the aftermath of gang rapes carried

out by Nigerians on teenage girls in Kildare, sustain several attacks on police by

Nigerian drug gangs, deal with one particularly nasty rape and murder of

a young Irish mother by a Nigerian immigrant, and attempt to control an African

gang called The Pesties who

“have been terrorising people prominently in the west and north of Dublin,

carrying out vicious assaults on delivery drivers and taxi men.”

African

and Muslim cab drivers have also been behind a large and growing number of

rapes and sexual assaults (for example, see here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here). In fact, sexual

offences in Ireland increased by 17% between

2017 and 2018. In financial terms, the expanding asylum process is costing the

Irish government more than €1 billion every

five years, and in the midst of an Irish housing crisis, immigration is putting immense pressure on

every aspect of the nation’s infrastructure.

Strangely,

the Irish media hasn’t been making much of this aspect of Ireland’s changing

complexion. Instead, much discussion has

taken place on the fact Ireland has no real “hate crime” laws with the

exception of the Prohibition of Incitement to Hatred Act 1989, which has

managed to achieve a grand total of five criminal convictions in the last 30

years. Dr Ali Selim, of the Islamic Cultural Centre in Dublin, has said “there

is a desperate need for hate crime legislation. Today we have a wide range of

diversity and faiths and that increases the need to have hate crime

legislation.” In a way, I agree with Dr Selim, because diversity inevitably

means restrictions on the freedoms of the native population. More migrants mean

more laws to protect those migrants from criticism.

But,

despite the interventions of Dr Selim, the origins of Irish conceptions of

“racism” and “hate speech” don’t lie among the growing Muslim population, but

among a very small number of influential Jews. In 1969, some 890 years after

Tairdelbach expelled the Norman-Jewish delegation, a young Jewish sociologist

arrived in Ireland from Israel. Ronit Lentin, the sociologist in question, was

Associate Professor of Sociology in Trinity College Dublin until her retirement

in 2014. From 1997 until 2012 Lentin was Head of Sociology, and acted as

director of the MPhil program in “Race, Ethnicity, Conflict.” She was also the

founder of the Trinity Immigration Initiative, from which she advocated an

open-door immigration policy for Ireland and opposed all deportations, as well

as engaging in activism to liberalise Irish abortion laws.[3] As

an academic and “anti-racist” activist, Lentin formulated what would become

some of the cardinal facets of Irish self-recrimination on matters of race,

beginning with her definition of Ireland as “a biopolitical racist state.”[4] By

her own account, before she began her work on stoking Irish race guilt in the

early 1990s, “most people were not conscious that Irish racism existed.”[5]

In

some senses, then, Lentin introduced the concept of an Irish racism. Her first

step in assuring the Irish that they were indeed racist was to deny their

existence as a people. She asserted that the Irish were merely “theorised as

homogeneous — white, Christian and settled.”[6]

Quite who had developed this theory of the Irish, and when, was never specified by Lentin, nor did she attempt to show that the white, Christian, and settled status of the vast majority of the Irish population was anything other than a matter of fact and reality. It appears to have sufficed for Lentin simply to assert that Irishness was nothing but a theory, and to leave it at that. She was particularly aggrieved by the fact the Irish, apparently unaware they were a figment of their own imagination, voted (80%) to link citizenship and blood (ending “birth-right citizenship) by constitutionally differentiating between citizen and non-citizen in a June 2004 Citizenship Referendum. This move was taken primarily in order to stop African “birth tourism” and “anchor babies” by African women, which had become increasingly common by the early 2000s. To Lentin, however, the move was symbolic of the fact “the Irish Republic had consciously and democratically become a racist state.”[7]

She concludes that any idea of the Irish as historical victims should be dispensed with, and that “Ireland’s new position as heading the Globalisation Index, its status symbol as the locus of “cool” culture, and its privileged position within an ever-expanding European Community calls for re-theorising Irishness as white supremacy.”[8]

[emphasis added]

Quite who had developed this theory of the Irish, and when, was never specified by Lentin, nor did she attempt to show that the white, Christian, and settled status of the vast majority of the Irish population was anything other than a matter of fact and reality. It appears to have sufficed for Lentin simply to assert that Irishness was nothing but a theory, and to leave it at that. She was particularly aggrieved by the fact the Irish, apparently unaware they were a figment of their own imagination, voted (80%) to link citizenship and blood (ending “birth-right citizenship) by constitutionally differentiating between citizen and non-citizen in a June 2004 Citizenship Referendum. This move was taken primarily in order to stop African “birth tourism” and “anchor babies” by African women, which had become increasingly common by the early 2000s. To Lentin, however, the move was symbolic of the fact “the Irish Republic had consciously and democratically become a racist state.”[7]

She concludes that any idea of the Irish as historical victims should be dispensed with, and that “Ireland’s new position as heading the Globalisation Index, its status symbol as the locus of “cool” culture, and its privileged position within an ever-expanding European Community calls for re-theorising Irishness as white supremacy.”[8]

[emphasis added]

So,

in Lentin’s worldview, Irishness is not only a fiction, but a racist, white

supremacist fiction. Lentin’s advice to the Irish, should they wish to rid

themselves of the delusion of peoplehood, is to enagage in mass celebrations of

“diversity and integration and multiracialism and multiculturalism and

interculturalism,”[9]

Lentin adds: “I propose an interrogation of how the Irish nation can become other than white.” Keeping up the family tradition, Ronit Lentin’s daughter Alana moved to Australia a few years ago, where she quickly established herself as an equally rabid promoter of White guilt and engaged in successive critiques of Australian “racism.” She is now President of the Australian Critical Race and Whiteness Studies Association, and has penned articles for The Guardian asserting that Australian identity is are fictional as that of the Irish, and demanding Australia adopt an open borders policy so that it too can become other than white.

Lentin adds: “I propose an interrogation of how the Irish nation can become other than white.” Keeping up the family tradition, Ronit Lentin’s daughter Alana moved to Australia a few years ago, where she quickly established herself as an equally rabid promoter of White guilt and engaged in successive critiques of Australian “racism.” She is now President of the Australian Critical Race and Whiteness Studies Association, and has penned articles for The Guardian asserting that Australian identity is are fictional as that of the Irish, and demanding Australia adopt an open borders policy so that it too can become other than white.

If

Ronit Lentin’s activism can be regarded as cultural sabotage, then that of her

co-ethnic Alan Shatter could be regarded as

nothing less than legislative warfare. Shatter, an Irish-born Jew, has

been discussed previously at The Occidental Observer, but not since 2013. Shatter’s

impact on Ireland has been extraordinary, and is difficult to exaggerate. His

first targets in government were the weakening of legislative controls that

helped maintain stability in the family (via the Judicial Separation and Family

Law Reform Act 1989), and the gradual erosion of highly conservative Irish laws

on contraception (by writing the 1979 satirical tract Family Planning — Irish Style, featuring mocking

illustrations designed by co-ethnic artist Chaim Factor). He has also been a

strident pro-abortion activist since at least 1983, and a very early proponent of homosexual

marriage and the adoption of children by homosexuals (he

was essentially the author of both bills). Shatter was also central to the

founding of the Oireachtas (Parliamentary) Committee on Foreign Affairs,

something he then used as a vehicle to pursue Zionist-friendly objectives. In

2013 The Times of Israel reported “Israel may finally have some luck

with the Irish” because “Israel could not have a more

understanding or reliable Irish ally than Shatter, a stalwart supporter even

during times of controversy. Occasionally combative, he has been highly

critical of previous governments’ strident criticisms of Israel, and he hasn’t

retreated from subsequent abuse.” The article made sure to celebrate the fact

Shatter enjoyed “an exceptionally influential position in the Irish government”

as both defense and justice minister, and noted that he “was particularly

active during the 1980s and ’90s in advocating for divorce and family-planning

rights. His urbane Jewish background appeared to put him at an advantage,

freeing him from the baggage that weighed on his Catholic counterparts.”

But

it was in his efforts in the field of immigration that Shatter demonstrated

real revolutionary zeal. Between 2011 and 2014, Shatter utterly transformed the

Irish citizenship process, personally granting Irish citizenship to 69,000

foreign nationals. In August 2013 he took steps to expand the Irish asylum

process, citing the Syrian Civil War as the reason but later conceding that the

highest number of asylum applications was actually coming from Nigerians and Pakistanis.

In fact, Shatter was so keen to boost the number of Africans entering Ireland

that the rejection rate for African asylum applications dropped from 47% to 3% as

soon as he took office. He was so celebrated in Africa that he won the Africa World Man of

the Year Award in

2012. Many of these asylum seekers, primarily Nigerians, have gone on to

terrorise and assault their hosts, while others have been noted as publicly masturbating in

their cabs during rush hour while they wait for customers. In 2013, Shatter

proposed a new bill that

would grant an amnesty to the thousands of illegal immigrants accumulating in

Ireland. And, in contrast with the reality of mass immigration — crime,

stretched resources, and the breaking down of a sense of community —

Shatter announced in 2014

that Ireland had to do more to “speak out and combat racism and related

intolerance” because:

This

recent migration … has had a transformative impact on Irish society – and, for

the better. Persons of non-Irish origin are playing an increasingly important

role in many walks of life, not least in sport, and have greatly enhanced the

social, cultural and economic fabric of our society. It is important that

Ireland remains a nation which welcomes those who have already settled here and

will do so in the future. It is equally important that we adapt to the

increasingly diverse nature of Irish society.

When

Shatter was forced to resign in May 2014 following a policing controversy, it

was the incomplete state of his immigration reforms that he told the press was

one of his biggest regrets. He told the Irish Times that one of his “big

frustrations” upon leaving office was the failure to publish “very

comprehensive” legislation in relation to immigration, residency and asylum,

and explained that he was “very disappointed” that his party colleague and

successor Minister for Justice Frances Fitzgerald appeared to be opting for a

less revolutionary Bill. He added:

Unfortunately,

the Bill I thought I would see published at least 18 months ago was on the

back-burner waiting to be dealt with … There was also great pressure to try and

fragment that legislation and deal solely with the asylum issue and not deal

with the very important reforms needed in the immigration area. I was concerned

if we dealt with the asylum area alone, we would never see the comprehensive

Bill that is needed. [The revised Bill] will not deal with overall immigration

reforms which are badly needed.

Although

Shatter was forced into early retirement, much damage had already been done,

and his legacy will continue.

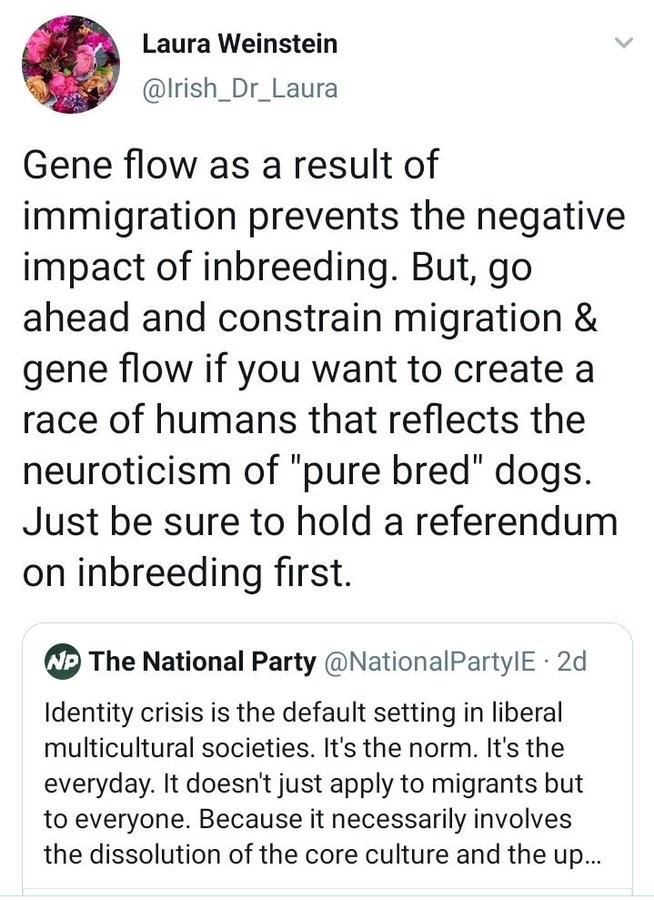

If

Shatter and Lentin weren’t enough, Twitter recently erupted due the recent

emergence of Laura Weinstein, a New York PhD who now lives in

Ireland and claims to be an expert in Irish history and culture. Of all the

aspects of Irish history and culture she could have chosen to focus on,

however, Dr Weinstein has decided she is most interested, like Lentin, in the

“myth” of a homogeneous Irish identity and “right wing Irish nationalism,” and

appears to employ her Twitter account, to a large degree, to the trolling of

Irish political figures opposed to mass immigration. Several days ago, for

example, she responded to a post by the National Party pointing out that

multiculturalism essentially results in identity crisis for all in society by

basically implying that Irish opposition to immigration would leave the Irish

like “neurotic” “inbred” “dogs.” She wrote: “Gene flow as a result of

immigration prevents the negative impact of inbreeding. But, go ahead and

constrain migration and gene flow if you want to create a race of humans that

reflects the neuroticism of “pure bred” dogs. Just be sure to hold a referendum

on inbreeding first.”

Now,

I’ve lived in Ireland for long periods during my life, and have shown American,

German, Finnish, and South African friends around the country. They were all

fascinated with the landscape, music, ancient history, and food, but, unlike

this Jewish woman, I can’t recall a single instance where one of them was in

any way concerned with the genetic homogeneity of the Irish. And not only is

Weinstein’s fixation exceedingly strange and unsettling, it’s also fanciful.

Genetic studies have shown the Irish already possess a diverse gene pool in

the form of genetic clusters of Scandinavian, Norman-French, British, and

Iberian origin. This is of course a considerably wider gene pool than that of

Dr Weinstein’s Ashkenazi Jews, who are all descended from a single group of 350 individuals.

Needless,

to say, Dr Weinstein provoked a robust reaction from Twitter because of her

response to the National Party, which in turn led her to make the even more

extraordinary claim that “No

one loves Ireland more than I do.”

We

can be sure that Lentin and Shatter would say the same thing. And perhaps they

do love Ireland, but not the Ireland that was, and has been for millennia, but

the Ireland that “is becoming” and is “to be” — the Ireland overcome by

globalism, with an international population devoid of the “white supremacy” of

Irishness. Perhaps they love the Ireland of gay pride parades and the arid

metallic stench of the abortion mills. Perhaps they love the Ireland touched by

Nigeria, the one sprinkled with mosques, and where young White mothers hang themselves in

homeless despair while asylum seekers are housed and fed mere yards away.

Perhaps they do indeed feel some kind of love, and they see what they’ve done,

and are doing, as the bringing of gifts to Ireland.

But

Tairdelbach’s lesson of a thousand years ago is that you don’t have to accept

them.

Notes

[1] A.

Beatty & D. O’Brien, Irish Questions and Jewish Questions: Crossovers in Culture (New York: Syracuse University

Press, 2018), 1.

[2] S.

Garner (2007). Ireland and immigration: explaining the absence of the far

right. Patterns

of Prejudice,

41(2) 109–130, 5.

[3] See

Lentin, R. (2013). A Woman Died: Abortion and the Politics of Birth in

Ireland. Feminist

Review, 105(1), 130–136.

[4] R.

Lentin, After

Optimism? Ireland, Racism and Globalisation (Dublin: Metro Eireann Publications,

2006), 3.

(Republished from The Occidental Observer by

permission of author or representative)