There can be no complete understanding of John Kennedy without some understanding of his father, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, for this is where he came from, not only in his own eyes and those of his friends, but in the eyes of his enemies too. The same is true for his brother Robert, of course.

I have emphasized before that, although very different in character, John and Robert Kennedy may be seen, from the point of view of their historical significance, as one person killed twice. But it should be stressed that their unity was grounded in their filial piety. I learned from David Nasaw’s biography, The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy (2012), that it was their father Joe who insisted that Jack name Bobby Attorney General, because “Jack needed someone in the cabinet in whom he had complete and absolute trust.” Robert didn’t like the idea, arguing that “nepotism was a problem,” and John was reluctant to pressure Bobby.

He decided to offer Bobby the number two position at the Defense Department and asked Clark Clifford, who was running his transition team, to go to New York to explain to [Joe] Kennedy, who had flown there after visiting Jackie and his new grandson in the hospital, why Bobby should not be named attorney general. Clifford agreed, though he thought it rather odd that the president-elect had asked “a third party to try to talk to his father about his brother.” Clifford met Kennedy at Kennedy’s apartment and presented his carefully rehearsed case against the appointment. “I was pleased with my presentation; it was, I thought, persuasive. When I had finished, Kennedy said, ‘Thank you very much, Clark. I am so glad to have heard your views.’ Then, pausing a moment, he said, ‘I do want to leave you with one thought, however — one firm thought.’ He paused again, and looked me straight in the eye. ‘Bobby is going to be Attorney General. All of us have worked our tails off for Jack, and now that we have succeeded I am going to see to it that Bobby gets the same chance that we gave to Jack.’ I would always,” Clifford recalled years later, “remember the intense but matter-of-fact tone with which he had spoken — there was no rancor, no anger, no challenge.” The father had spoken, and his sons, on this issue at least, were expected to obey.[1]

Although there is no recorded statement to that effect, Joe probably envisioned that Robert could succeed Jack as president in 1968. And it is easy to imagine that, had John survived and been reelected in 1964, Robert, with John’s support and under his watch, could have inherited the White House. We may ponder what the world would be like today had there been Kennedys in the White House until 1976.

John and Robert shared a common horror of modern war, and that, too, was their father’s legacy. John was a genuine war hero decorated with the Navy and Marine Medal for “extremely heroic conduct.” Yet on Victory in Europe Day, May 8, 1945, as a young journalist covering the founding conference of the United Nations in San Francisco, he wrote in the Herald-American: “Any man who had risked his life for his country and seen his friends killed around him must inevitably wonder why this has happened to him and most important what good will it do. . . . it is not surprising that they should question the worth of their sacrifice and feel somewhat betrayed.”[2] When announcing his candidacy for Congress on April 22, 1946, JFK declared: “Above all, day and night, with every ounce of ingenuity and industry we possess, we must work for peace. We must not have another war.”[3] Hugh Sidey, one of his journalist friends, wrote about him: “If I had to single out one element in Kennedy’s life that more than anything else influenced his later leadership it would be a horror of war, a total revulsion over the terrible toll that modern war had taken on individuals, nations, and societies, and the even worse prospects in the nuclear age. . . . It ran even deeper than his considerable public rhetoric on the issue.”[4] John once said to his friend Ben Bradlee that he believed that “the primary function of the president of the United States [was] to keep the country out of war.”[5]

That was the conviction that had guided his father throughout his political life in Franklin Roosevelt’s government, until his resignation in December 1940. As U.S. ambassador to London, Joe Kennedy wholeheartedly supported Neville Chamberlain’s policy of “appeasement” in 1938-39. He wanted peace as passionately as Churchill wanted war. “I am pro-peace, I pray, hope, and work for peace,” Joe declared on his first return from London to the U.S. in December 1938.[6] For this, he ended in the wrong side of history, which Churchill took care to write himself.

The Stain of Appeasement

Like his father, President Kennedy was a determined peacemaker, and those in the Pentagon who wanted to push the U.S. into a third world war tried to destabilize him with insinuations that he was an appeaser like his father. On October 19, 1962, in the heat of the Cuban Missile Crisis, as Kennedy resolved to blockade Soviet shipments rather than bomb and invade Cuba, General Curtis LeMay scornfully told him, “This is almost as bad as the appeasement at Munich . . . I just don’t see any other solution except direct military intervention right now.”[7]

The stain of his father’s record as a Hitler-appeaser had followed John like a shadow. Although the press had not published it, it was no secret in the Pentagon and the CIA that the U.S. army had discovered in 1946, in Berlin’s Foreign Office, reports about Joe’s meetings with German ambassador von Ribbentrop and his successor von Dirksen, that said that Joe was Germany’s “best friend” in London and “understood our Jewish policy completely.”[8]

In a joint debate during the 1960 Democratic convention, Johnson had attacked John as being the son of a “Chamberlain umbrella man” who “thought Hitler was right.”[9] During Kennedy’s presidential campaign, the Israeli press worried that Kennedy’s father “never loved the Jews and therefore there is a question about whether the father did not inject some poisonous drops of anti-Semitism in the minds of his children, including his son John’s.”[10] Abraham Feinberg recalls that when he invited Kennedy to his apartment to discuss his campaign funding with “all the leading Jews,” one of them set the tone with this remark: “Jack, everybody knows the reputation of your father concerning Jews and Hitler. And everybody knows that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.” Kennedy came back outraged from that meeting (but with the promise of $500,000).[11] When meeting the new president on May 30, 1961 in New York, Ben-Gurion could not help but see in him the son of a Hitler-appeaser. Feinberg (who arranged the meeting) recalls that “Ben-Gurion could be vicious, and he had such a hatred of the old man [Joe Kennedy].”[12]

Is Joe’s bad reputation among Jews relevant to the assassination of his two sons? Many Jewish authors think it is. In his book The Kennedy Curse, purporting to explain “why tragedy has haunted America’s first family for 150 years”, Edward Klein links the “Kennedy curse” to Joe’s anti-Semitism, citing a story “told in mystical Jewish circles” (perhaps made up by Klein) according to which, in “retaliation” to some remark Joe made to “Israel Jacobson, a poor Lubavitcher rabbi and six of his yeshiva students, who were fleeing the Nazis,” “Rabbi Jacobson put a curse on Kennedy, damning him and all his male offspring to tragic fates.”[13] Ronald Kessler, for his part, wrote a book titled, The Sins of the Father — a not so subtle allusion to Exodus 20:5: “I, Yahweh, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me.” Naturally, for Kessler, Joe Kennedy’s worst sin was that “he was a documented anti-Semite and an appeaser of Adolf Hitler” who “admired the Nazis.”[14]

The “Kennedy curse” did run into the third generation and possibly the fourth, when John’s only son died in a suspicious plane accident on July 16, 1999, with his wife, possibly pregnant. Five days later, John Podhoretz, son of neoconservative luminary Norman Podhoretz, published in the New York Post an opinion piece titled “A Conversation in Hell” in which he imagined Satan speaking to Joe Kennedy in Hell. The devil rejoices at the idea of eternally torturing Joe for “saying all those nice things about Hitler,” and brags of having caused the death of his grandson because, he says: “When I make a deal for a soul like yours, I need to season it before I’m ready to put it in the infernal oven.” This hateful fantasy, which is reminding of the Talmud’s depiction of Jesus in Hell, illustrates the devouring hatred of some Jewish intellectuals toward the Kennedys, and the root of that hatred in Joe Kennedy’s effort to prevent the Second World War.[15]

Interestingly, Podhoretz’s devil (or is it Yahweh?) accuses Kennedy of having done “everything you could to prevent Jewish emigration from Nazi Germany. Thousands of Jews died because of you.” The truth is exactly the opposite. In 1938, the “Kennedy Plan”, as the press called it, was to rescue German Jews. Since the U.S. government refused to open its borders to Jewish refugees, and since Great Britain strictly limited Jewish immigration to Palestine, Joe was urging the British government to open up its African colonies for temporary resettlement. “To facilitate the resettlement process,” Nasaw writes, “Kennedy volunteered to Halifax that he ‘thought that private sources in America might well contribute $100 or $200 million if any large scheme of land settlement could be proposed.’”[16] The plan was presented to Chamberlain just days after Kristallnacht (9-10 November 1938), and was supported by Jewish financier Bernard Baruch. But it angered the Zionists, who didn’t want to hear about any Jewish emigration except to Palestine, because, Ben-Gurion said, it “will endanger the existence of Zionism.”[17] Therefore, today, the “Kennedy Plan” is reviled as a kind of “final solution to the Jewish question,” and further proof that Joe was Israel’s mortal enemy.[18]

If Jewish hatred of Joe Kennedy could still inspire Podhoretz’s nasty column in 1999, imagine how deep it ran in the 1960s. At the height of his showdown with JFK over Dimona, 25 April 1963, Ben-Gurion wrote him a seven-page letter explaining that his people was threatened with extermination by a newly formed Arab Federation, just like when “six million Jews in all the countries under Nazi occupations (except Bulgaria), men and women, old and young, infants and babies, were burnt, strangled, buried alive.” “Imbued with the lessons of the Holocaust,” Avner Cohen comments, “Ben Gurion was consumed by fears for Israel’s security.”[19] He was enraged by what he saw as Kennedy’s obvious lack of concern for his people’s security, and at this point, he must have decided that Kennedy was indeed his father’s son, a modern-day Haman.

Before we get to the main piece of evidence of a direct relationship between Joe Kennedy’s appeasement policy and John Kennedy’s assassination, let us get an overview of Joe’s public career, using mainly David Nasaw’s biography and on Michael Beschloss’s Kennedy and Roosevelt: The Uneasy Alliance (1979).

The Ambassador

Joe Kennedy entered national politics as a supporter of Roosevelt in his first presidential campaign in 1932. In July 1934, Roosevelt asked him to chair the newly created Securities and Exchange Commission, charged with bringing the New Deal to Wall Street by regulating and disciplining the Stock Exchange market. Kennedy announced: “the days of stock manipulation are over. Things that seemed all right a few years ago find no place in our present-day philosophy.” According to Beschloss, Kennedy “won almost universal praise for his salesmanship, political acumen, and ability to moderate conflicting sides that encouraged capital investment and economic recovery.” “Few were more impressed by Kennedy’s accomplishment than the man who hired him,” and “Joseph Kennedy increasingly became a familiar figure at the White House.”[20]

In 1936, Joe supported Roosevelt’s second campaign with a book titled I’m for Roosevelt (mostly ghost-written by Arthur Krock). He was hoping to be named Secretary of the Treasury, but Henry Morgenthau Jr. also wanted the job, and got it. Instead, Roosevelt named Joe chairman of the Maritime Commission, and one year later made him ambassador to London. As war was brooding in Europe, this was an important position, and Joe made it more important by often overstepping his Secretary of State Cordell Hull’s instructions.

He supported Chamberlain’s position that the territorial integrity of Czechoslovakia was not worth a war, declaring in September 2, 1938, “for the life of me I cannot see anything involved which could be remotely considered worth shedding blood for,” a statement for which he was reprimanded by Hull and Roosevelt.[21] On October 19, Joe began another speech by jokingly listing the topics he had decided not to talk about, including “a theory of mine that it is unproductive for both democratic and dictator countries to widen the division now existing between them by emphasizing their differences, which are self-apparent.”[22] Hull held a press conference the next morning to clarify that Kennedy had been speaking for himself, not the government, and Roosevelt delivered his own display of belligerence: “There can be no peace if national policy adopts as a deliberate instrument the threat of war.”[23]

In the meantime, without informing Hull, Kennedy had summoned Charles Lindbergh to London and asked him to write a letter, to be forwarded to Washington and to Whitehall, summarizing his view regarding the strength of the Luftwaffe. Lindbergh had just visited German airfields (and been presented the Service Cross of the German Eagle by Goering), and concluded that the Luftwaffe would be unassailable in a war of the skies. Kennedy then arranged a meeting between Lindbergh and an official of the British air ministry.[24] His diplomatic strategy consisted in trying to convince the British that Germany was unbeatable and that the U.S. wouldn’t join the fight, so that the British had better come to terms with Germany, whose territorial claims were justified anyway.

In the same period, Joe made plans to meet in Paris with Dr. Helmuth Wohlthat, Goering’s chief economic adviser, with whom he had made contact through James Mooney, the president of General Motors Overseas. As Nasaw explains, “Kennedy was in effect laying the groundwork for a new appeasement strategy, one that would buy Hitler off by providing him with the means to convert his war economy to a peace economy.”[25] Hull forbade him to go to Paris, so Joe met Wohlthat in London without informing Hull.

In August 23, 1939, a week before Hitler invaded Poland, Kennedy urged Roosevelt, in vain, to pressure the Polish government to cede territory to Germany.[26] After Hitler’s invasion, Kennedy, like Chamberlain, was heartbroken: “It’s the end of the world . . . the end of everything,” he told Roosevelt on the phone.[27] But a week later, he was still urging him to save peace, writing him: “It seems to me that this situation may crystallize to a point where the President can be the savior of the world. The British government as such certainly cannot accept any agreement with Hitler, but there may be a point when the President himself may work out plans for world peace.”[28] He got his response from Hull: “The people of the United States would not support any move for peace initiated by this Government that would consolidate or make possible a survival of a regime of force and of aggression.”

Simultaneously, Roosevelt was initiating direct contact with Churchill, now First Lord of the Admiralty and soon to be Prime Minister. From Roosevelt’s letters, Churchill got enough confidence that the U.S. would ultimately join the war if it broke out, and he bet everything on it. Joe was infuriated when learning about this most irregular channel of communication, at a time when the President was bound by neutrality laws and the American people overwhelmingly opposed to U.S. engagement. Joe was particularly distressed by Roosevelt’s trust in Churchill, whom Joe considered “an actor and a politician. He always impressed me that he’d blow up the American Embassy and say it was the Germans if it would get the U.S. in.”[29] In early December 1939, Kennedy confided to Jay Pierrepont Moffat of the State Department that Churchill “is ruthless and scheming. He is also in touch with groups in America which have the same idea, notably, certain strong Jewish leaders.”[30]

After the defeat of France, Kennedy saw a new opportunity for peace. He cabled Washington on May 27, 1940, recommending that the President push Britain and France to negotiate an end to the crisis, as Lord Halifax, still Foreign Secretary, was actually proposing. “I suspect that the Germans would be willing to make peace with both the French and British now — of course on their own terms, but on terms that would be a great deal better than they would be if the war continues.”[31]

Although aware that Roosevelt was now ignoring him, Joe remained at his post until October 1940. Before leaving, he wrote a note to Chamberlain, then a broken and dying man: “For me to have been any service to you in your struggle is the real worthwhile epoch in my career. You have retired but mark my words the world will yet see that your struggle was never in vain. My job from now on is to tell the world of your hopes. Now and forever, Your devoted friend, Joe Kennedy.”[32] Joe Kennedy was still a convinced appeaser, determined to give peace every chance.

David Irving mentions that, before boarding a ship from Lisbon to New York, Kennedy “pleaded with the State Department to announce that, even if this vessel mysteriously blew up in mid-Atlantic with an American ambassador on board, Washington would not consider it a cause for war. ‘I thought,’ wrote Kennedy in his scurrilous unpublished memoirs, ‘that would give me some protection against Churchill’s placing a bomb on the ship.’”[33]

Kennedy arrived in New York October 27, a week before election day. He knew enough of Roosevelt’s secret contacts with Churchill to endanger his reelection. He was seriously considering speaking out to the press. In a wire to his lover and admirer Clare Booth Luce, he promised a bombshell that would “put twenty-five million Catholic voters behind [Republican candidate] Wendell Willkie to throw Roosevelt out.”[34]

But Joe had a strong sense of loyalty, and his wife reminded him of a political truth instinctive to them both: “The President sent you, a Roman Catholic, as Ambassador to London, which probably no other President would have done. . . . You would write yourself down as an ingrate in the view of many people if you resign now.”[35] After a long conversation with Roosevelt on the day of his arrival, of which nothing has transpired, Kennedy gave a radio address over CBS on October 29 to endorse Roosevelt, but not without reasserting his “conviction that this country must and will stay out of war.” A few days later, with Joe Kennedy by his side, Roosevelt made his own pledge: “I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again and again: Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars!”[36] Roosevelt was elected. On December 1, 1940, Kennedy delivered his resignation letter, and told reporters: “My plan is . . . to devote my efforts to what seems to me to be the greatest cause in the world today . . . That cause is to help the President keep the United States out of war.”[37]

On December 17, Roosevelt revealed at a press conference his plans to provide billions of dollars in war supplies to Great Britain in the form of Lend-Lease (eventually, the U.S. would supply England with $13 billion). Joe expressed privately his feeling of having been exploited by the President. But he stayed in relatively good terms with Roosevelt, although he refused to support his nomination for a fourth term, when he visited him on October 26, 1944 in the White House. Kennedy recorded in his notes telling the President — a very sick man — that the Catholic voters were hesitant to vote for him because “they felt that Roosevelt was Jew controlled.” He added that he agreed “with the group who felt that the Hopkins, Rosenmans, and Frankfurters, and the rest of the incompetents would rob Roosevelt of the place in history that he hoped, I am sure, to have. . . . Roosevelt went on to say ‘Why, I don’t see Frankfurter twice a year.’ And I said to him, ‘You see him twenty times a day but you don’t know it because he works through all these other groups of people without your knowing it.’”[38]

After his resignation in 1941, Joe had envisioned writing a memoir of his London years, and told his friend and former president Herbert Hoover that the book would “put an entirely different color on the process of how America got into the war and would prove the betrayal of the American people by Franklin D. Roosevelt.” But, Beschloss comments, “the necessities of wartime unity and, later, his sons’ political careers kept Joseph Kennedy’s diplomatic memoir out of print, where it remained.”[39]

Here, there is an interesting parallel with James Forrestal, another American patriot of Irish Catholic stock and a friend of Joe Kennedy. As David Martin shows in his book The Assassination of James Forrestal (summarized here), when Forrestal was pushed out of the Defense Department by Truman in March 1949, he planned to write a book and to start a magazine. As Navy Secretary, he had gained inside knowledge of Roosevelt’s scheme to provoke the Japanese into attacking Pearl Harbor. In 1945, he had worked behind the scene to achieve a negotiated surrender from the Japanese, and was very bitter about Roosevelt’s demand for “unconditional surrender” and the unnecessary suffering imposed on the Japanese. Forrestal had also much to say about the way the Zionists obtained the Partition Plan at the U.N. General Assembly, or about the way Truman was bought into supporting the recognition of Israel. On April 2, 1949, Forrestal was interned against his will and forcibly confined in the 16th floor of the Navy hospital of Bethesda, and on May 22 was declared to have fallen from a window while trying to hang himself from it with a dressing-gown sash. No criminal investigation was conducted, but the evidence obtained by David Martin through a Freedom of Information Act leaves no doubt that he was assassinated by the Zionist mafia.

It is easy to imagine that, had Joe Kennedy decided to expose Roosevelt’s betrayal of the American people and the Jewish intrigues to push him into the war, he might have suffered the same fate as Forrestal. Instead, he retired from public life and devoted his remaining influence to his sons’ political future. Despite the death of his eldest son Joe Jr. in a high-risk mission in 1944, he achieved his presidential ambition through his second son. The “Kennedy curse,” however, would ultimately catch up with his lineage.

John Kennedy’s Intellectual Filiation

John has always been loyal to his father’s memory, and there is enough evidence that he shared his most fundamental principles and his views of World War II. In 1956, in his book Profiles in Courage, John praised Senator Robert Taft for having, at tremendous personal cost, denounced in 1946 the hanging of eleven Nazi officials as “a blot on the American record which we shall long regret.”[40] One symbolic hint of President Kennedy’s intellectual and political filiation with his father was his invitation of Charles Lindbergh on May 11, 1962, for a grand reception at the White House. Lindbergh and his wife caused a sensation when they dined at the presidential table and stayed overnight at the White House.[41] Let’s recall that, in September 1940, Lindbergh had been a founding member of the America First Committee and the staunchest critic of Roosevelt’s ploys to drag the U.S. into the war.[42] His reputation had suffered tremendously from his criticism of Jewish influence, and he had been living as a recluse ever since.

Kennedy had nothing to gain politically from inviting Lindbergh very publicly to the White House. The significance of this gesture should not be underestimated. It probably demonstrates a wish to vindicate the vilified appeasers of 1938-40. Lindbergh at the White House may have been a sign that the wheel was turning, and that history would soon be written in a more balanced way. John’s assassination halted and reversed this movement. Half a decade later, along with the expansion of Israel, the dark cult of the Holocaust would start swamping over the U.S. and the world. Arguably, if Kennedy had lived, there would be no compulsory Holocaust religion today.

For those like David Ben-Gurion whose self-image and worldview revolved around the Holocaust, the Kennedy brothers were essentially sons of a Hitler-appeaser and Nazi-supporter, and their leadership of the United-States was an existential threat as well as an intolerable insult. Although, for obvious reasons, this murderous hatred is seldom expressed publicly (John Podhoretz’s “A Conversation in Hell” is a remarkable exception), it is a critical fact to take into account in our quest to solve the mystery of the “Kennedy curse.” And it sheds a bright light on one of the most bizarre aspects of JFK’s assassination.

In his 1967 book titled Six Seconds in Dallas: a micro-study of the Kennedy assassination proving that three gunmen murdered the President, Josiah Thompson first drew attention to a character who can be seen on the Zapruder film and on other photographs taken in Dealey Plaza at the moment of JFK’s assassination. Here is how Thompson presents him in a short video recorded by Errol Morris for the New York Times in 2011:

On November 22nd, it rained the night before. But everything cleared by about 9 or 9:30 in the morning. So if you were looking at various photographs of the motorcade route, in the crowd gathered there, you will have noticed: nobody is wearing a raincoat, nobody has an open umbrella. Why? Because it’s a beautiful day. And then I noticed: in all of Dallas, there appears to be exactly one person standing under and open black umbrella. And that person is standing where the shots began to rain into the limousine. Let us call him “the umbrella man”. . . . You can see him in certain frames from the Zapruder film, standing right there by the Stemmons Freeway sign. There are other still photographs taken from other locations in Dealey Plaza, which shows the whole man standing under an open black umbrella — the only person under any umbrella in all of Dallas, standing right at the location where all the shots come into the limousine. Can any one come up with a non-sinister explanation for this? So I published this in Six Seconds, but didn’t speculate about what it meant . . . Well, I asked that the Umbrella Man to come forward and explain this. So he did. He came forward and he went to Washington with his umbrella, and he testified in 1978 before the House Select Committee on Assassinations. He explained then why he had opened the umbrella and was standing there that day. The open umbrella was a kind of protest, a visual protest. It wasn’t a protest of any of John Kennedy’s policies as president. It was a protest at the appeasement policy of Joseph P. Kennedy, John Kennedy’s father when he was ambassador to the court of Saint James in 1938 and 39. It was a reference to Neville Chamberlain’s umbrella.[43]

The black umbrella had been Chamberlain’s iconic trademark, and, after his return from Munich, a symbol of “appeasement”, both for those who supported it (some old ladies “suggested that Chamberlain’s umbrella be broken up and pieces sold as sacred relics”)[44] and for those who opposed it (“Wherever Chamberlain traveled, the opposition party in Britain protested his appeasement at Munich by displaying umbrellas,” according to Edward Miller).

The Umbrella Man was Louie Steven Witt, and had been identified by local newsmen before he came forward to the HSCA. Josiah Thompson assumes that his “visual protest” and JFK’s assassination are unrelated, and that they happened at the exact same time and place by some kind of quantum-physics coincidence. He cannot bring himself to see the connection, even though the Umbrella Man himself made it clear to the HSCA that he wanted to “heckle” JFK about his father’s appeasement of Hitler in 1938. Knowing what we know about Jewish perception of the “Kennedy curse” as linked to the “sins of the father”, we cannot but find Thompson’s refusal to see anything conspiratorial as very typical of Gentile self-induced blindness.

Was Louie Steven Witt a Zionist agent, a sayan? Not necessarily. He might have been instructed to do what he did without knowing that Kennedy would be killed right in front of him. On the other hand, the explanation he gave for his “bad joke” sounds disingenuous: “In a coffee break conversation,” he said, “someone had mentioned that the umbrella was a sore spot with the Kennedy family. . . . I was just going to kind of do a little heckling.” Witt carefully avoided mentioning why the umbrella was “a sore spot with the Kennedy family.” He also avoided naming Joe Kennedy when he said that he had heard that “some members of the Kennedy family” had once been offended in an airport by people brandishing umbrellas. The “airport” sounds like an allusive reference to Chamberlain’s widely publicized return at the Heston Aerodrome on 30 September 1938. There is clearly a cryptic undertone in Witt’s explanation. For those Unz Review readers who have ears to hear and eyes to see, executing JFK while “heckling” him about his father’s appeasement policy should be an unmistakable signature. Chamberlain’s umbrella is Kennedy’s cross.

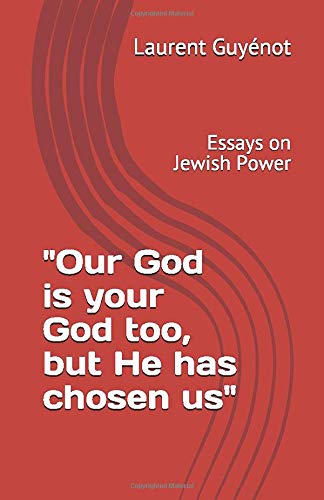

Laurent Guyénot, Ph.D., is the author of The Unspoken Kennedy Truth(2021), Essays on Jewish Power(2020), and From Yahweh to Zion (2018).

Notes

[1] David Nasaw, The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy, Penguin Books, 2012, pp. 818-819.

[2] Christ Matthews, Jack Kennedy, Elusive Hero, Simon & Schuster, 2011, pp. 71-72.

[3] James Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters, Touchstone, 2008, p. 5.

[4] Quoted in Robert Kennedy, Jr., American Values: Lessons I Learned from My Family, HarperCollins, 2018, p. 101.

[5] Quoted in Robert Kennedy, Jr., American Values, p. 101.

[6] Michael R. Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt: The Uneasy Alliance, Open Road, 1979, p.187.

[7] Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable, p. 21.

[8] Nasaw, The Patriarch, p. 349.

[9] Robert Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson, vol. IV: The Passage of Power, Alfred Knopf, 2012, p. 104. Also in Arthur Krock, Memoirs: Sixty Years on the Firing Line, Funk & Wagnalls, 1968, p. 362.

[10] In the journal of the Herut, Menachem Begin’s political party, quoted in Alan Hart, Zionism: The Real Enemy of the Jews, vol. 2: David Becomes Goliath, Clarity Press, 2013, p. 252.

[11] Seymour Hersh, The Samson Option: Israel’s Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy, Random House, 1991, p. 96.

[12] Hersh, The Samson Option, p. 103.

[13] Edward Klein, The Kennedy Curse: Why Tragedy Has Haunted America’s First Family for 150 Years, Saint Martin’s Press, 2004.

[14] Ronald Kessler, The Sins of the Father: Joseph P. Kennedy and the Dynasty He Founded, Coronet Books, 1997, quotes from the publisher’s presentation and the back cover.

[15] John Podhoretz, “A Conversation in Hell,” New York Post, July 21, 1999, on nypost.com

[16] Nasaw, The Patriarch, pp. 403-406.

[17] Alan Hart, Zionism: The Real Enemy of the Jews, vol. 1: The False Messiah, Clarity Press, 2009, p. 164.

[18] Clive Irving, “Joe Kennedy’s answer to the Jewish question: ship them to Africa,” Apr. 14, 2017, on www.thedailybeast.com

[19] Avner Cohen, Israel and the Bomb, Columbia UP, 1998, pp. 10, 119.

[20] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, pp. 105-109.

[21] Nasaw, The Patriarch, p. 373; also Beschloff, Kennedy and Roosevelt, p. 180.

[22] Nasaw, The Patriarch, p. 396.

[23] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, pp. 185-186.

[24] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, p. 182.

[25] Nasaw, The Patriarch, p. 425.

[26] Nasaw, The Patriarch, p. 445.

[27] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, p. 199.

[28] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, p. 201.

[29] Nasaw, The Patriarch, pp. 460-461. The quote is from Joe Kennedy’s diary, according to David Irving, who renders it slightly differently in Churchill’s war, vol. 1: The Struggle for Power, Focal Point, 2003, p. 207.

[30] Nasaw, The Patriarch, p. 476.

[31] Nasaw, The Patriarch, p. 496.

[32] Nasaw, The Patriarch, p. 534.

[33] David Irving, Churchill’s war, vol. 1: The Struggle for Power, Focal Point, 2003, p. 207.

[34] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, pp. 15-16.

[35] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, pp. 43 and 230.

[36] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, pp. 235-237.

[37] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, p. 247.

[38] Nasaw, The Patriarch, p. 625; Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, p. 279.

[39] Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt, p. 273.

[40] Robert Taft, October 6, 1946, quoted in John F. Kennedy, Profiles in Courage, 1956, Harper Perennial, 2003 , p. 199.

[41] “Visit of Charles A. Lindbergh”, on www.jfklibrary.org

[42] Lynne Olson, Those Angry Days: Roosevelt, Lindbergh, and America’s Fight Over World War II, 1939-1941, Random House, 2013.

[43] “The Umbrella Man”, on Vimeo.com or YouTube

[44] Patrick J. Buchanan, Churchill, Hitler, and “The Unnecessary War”: How Britain Lost Its Empire and the West Lost the World, Crown Forum, 2008, p. 208.

https://www.unz.com/article/